“When Video Attacks: The Art of the Video Mix.” Found Footage Magazine 10 (October 2024): 48-59.

Video mixtape is a term that describes hand-made VHS collage tapes primarily consisting of found footage re-recorded from movies, television, and home videos. Some call them “video complications,” while others colloquially refer to them as “VHS shit mixes,” “video cut-ups,” “scratch videos” (as the British call them), and to a few lonesome (or perhaps hopeful) creators they are “party tapes.”1 Historically, such video collages were self-distributed, with the practice’s most popular titles being bootlegged and eventually shared on peer-to-peer networks. Although a small number of them have been commercially produced, none would be considered commercially successful.

A wide majority of video mixtapes are compiled from short clips, often dubbed from other source videotapes, which mixtape creator-collectors consider to be the best of the best or the weirdest of the weird. They offer up some of the most extreme, bizarre, and sensational clips from people’s individual video collections. A few even include original material produced specifically for the mix. Some of the more extreme video mixtapes were officially (or unofficially) banned, an aspect that appeals to gore-hounds since it suggests this morally corrupt material is offensive enough to inspire some government bureaucrat to try to stop audiences from seeing it. Warning labels attached to tapes not only inform that the content is shocking, but also functioned as a challenge to potential viewers: Do you have the intestinal fortitude necessary to engage with this material?

In this paper, I consider a diverse range of video mixtapes to discuss their different aesthetic aspects while highlighting several of the most-discussed and paradigmatic works. I argue that the video mixtape can be seen as an extension of mondo film and the shockumentary, but also has roots in experimental cinema, video art, and zine culture. I will also demonstrate that these tapes provide a meta-commentary on the culture in which they were produced.2

Scratching Up the Atrocity Exhibition

Some of the earliest roots of the video mixtape can be traced to the British post-punk and industrial music scene of the early 1980s, in particular SPK, Psychic TV, and the Scratch Video movement, which was in turn heavily influenced by J. G. Ballard and William S. Burroughs. Ballard’s novel The Atrocity Exhibition is an experimental, dystopian novel constructed like a bricolage of texts that deal with psychological fragmentation, the eroticization of violence, and media-driven culture. The original edition featured a preface by Burroughs, a writer whom Ballard deeply admired and whose experimental structuring the book borrows from. In the RE/Search edition of The Atrocity Exhibition, publishers V. Vale and Andrea Juno suggest that the structure of the book “resembles a flickering video-collage in written form.”3 Given Ballard’s influence on the post-punk and industrial music scenes of the late 1970s and 1980s, it’s hardly surprising that some of the first video mixes came out of the industrial music scene. It is worth noting—if only as a piece of information for your next trivia night—that the first music video played on MTV was The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star,” directly inspired by Ballard’s short story The Sound-Sweeper.4

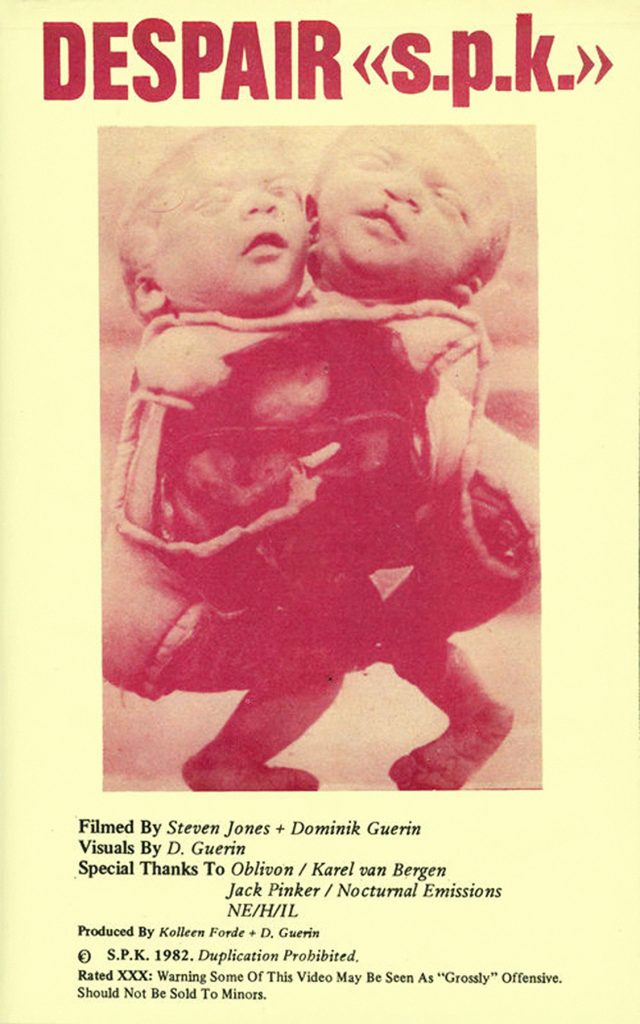

Despair (1982) by SPK, an industrial noise group founded by Graeme Revell, is one of the earliest examples of a video mixtape, and through Revell it is possible to trace some of the influence that Ballard may have had on the practice. In a 1983 article in the UK weekly Sounds, Revell declared Ballard as “science fiction’s greatest living writer.” Revell later refers to Ballard as “one of the few thinkers and commentators on society who can do more than lament lost humanism or morality. He takes his place with Barthes, Baudrillard, and Deleuze, with the added bonus that he is FUN to read.”5 In a 1983 discussion with journalist Thomas Frick, Ballard would reveal that he met with Revell a week before.6

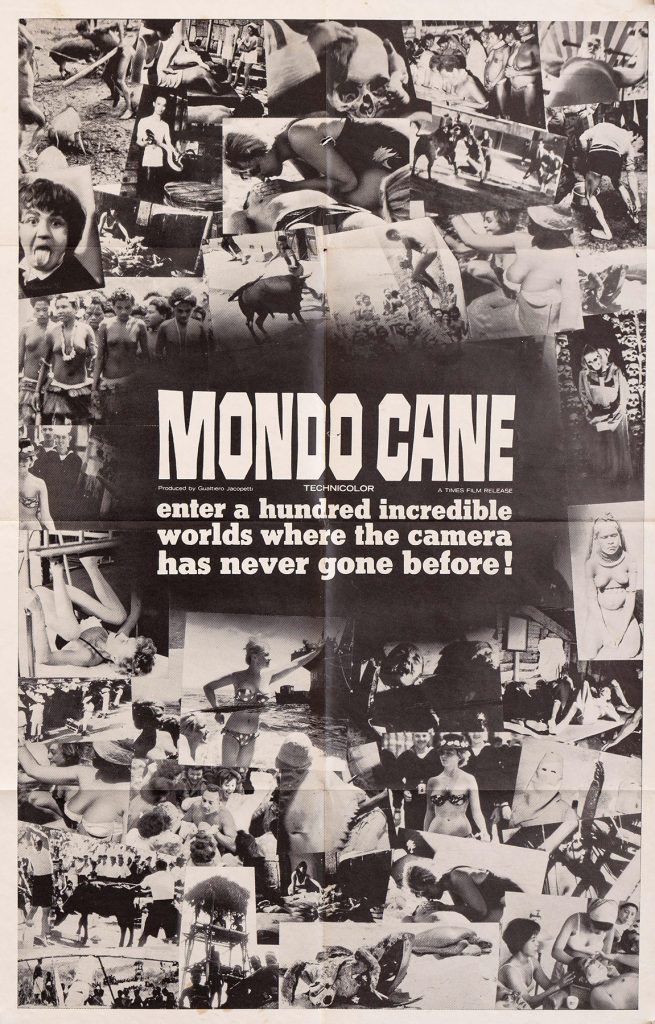

In Frick’s interview, Ballard recounts that a videotape was sent to him and that his daughter had to watch it for him as he didn’t own a VCR. His daughter reported back, “it’s rather weird, all about autopsies.”6 Since the origin of the tape is unclear, we can only speculate that his daughter might have watched SPK’s Despair, a tape brimming with autopsy footage; however, this is unlikely given that Ballard never mentioned it to Revell.7 In a 2006 interview with mondo scholar Mark Goodall, Ballard—who was a “great admirer” of Mondo Cane (Gualtiero Jacopetti, Paolo Cavara, and Franco E. Prosperi, 1962)—is quick to distinguish mondo cinema from video compilations observing that the Mondo Cane films “were quite stylistically made and featured good photography, unlike some of the ghastly compilation atrocity footage I’ve been sent.”8

Ballard refers to extreme video compilations as “ghastly,” yet he defends the violence in Mondo Cane, a sensationalist pseudo-travelogue that attempts to provide glimpses into primitive cultural practices around the world with the intention to shock Western film audiences. He argues: “We needed violence and violent imagery to drive the social (and political) revolution that was taking place in the mid-1960s—violence and sensation, more or less openly embraced, were pulling down the old temples.”9 As such, the video mixtape can be seen as responding to an era of moral panic, religious fanaticism, and media sensationalism—a response intended to offend, challenge societal norms, and push the boundaries of moral decency. Ironically, Ballard’s writing does this as well. In contrast to Mondo Cane, which was extremely well-financed by the wealthy Italian producer publishing mogul Angelo Rizzol, Despair was a DIY production made with comparatively little money, even if the cost of video equipment in that era is taken into consideration.10 Nevertheless, what it lacked in budget and production values, it made up for in aggression and shock value.

The original Despair VHS was principally sold by the band through mail order, and its packaging features a conjoined fetus with the warning: “Rated XXX: Warning some of this video may be seen as ‘grossly’ offensive. Should not be sold to minors.” The Despair tape is a video compilation that features SPK’s brand of noisy post-punk industrial music, and contains footage of the band playing live, autopsy footage, the slicing of a dead cat’s eyeball (reminiscent of the iconic scene from Buñuel’s 1929 Un chien andalou), and oral sex performed with the head of a fake corpse. In short: an exhibition of atrocities that includes mages of the Holocaust, brain operations, and fetal deformities. Some viewers assumed the corpse footage was real, perhaps most famously Frank Henenlotter, the director of the video nasty Basket Case (1982), who stated: “When I saw the video I thought, ‘What a fabulous thing; what a strange way of using music. Who would make a music video to such horror—with actual severed heads…’”11

Like SPK’s music, Despair is harsh and shocking. In David Kerekes and David Slater’s 1994 book, Killing for Culture, they describe SPK’s extreme mixtape as moving “aimlessly from one grotesque [scene] to another,” and suggest that the tape’s “obstreperous imagery can only flounder under its own shocking weight.”12 Granted, this video was radical and provocative when it was first released, but like most things that were once avant-garde, it is now cliché (or, perhaps, audiences are simply more desensitized).

Another early example of a video mixtape is First Transmission (1982) made by Psychic TV, the audio-video component of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, a performance ensemble/band/cult formed by Alex Fergusson and ex-Throbbing Gristle members Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Peter Christopherson. While Despair is shocking for its own sake, Psychic TV’s tape (equally horrific) had more ambitious or, perhaps, pretentious aims. When describing First Transmission in Thee Grey Book, an introduction to Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth released in 1982, P-Orridge writes:

Psychic TV is not intended to be a replacement for conventional programming, but rather the first step towards a de-programming, without regard for the preoccupations of commercial TV, or redundant assumptions about entertainment and value. At Psychic TV we accept and exploit the way TV is used by our generation, as raw material to be manipulated by the viewer. […] Everything will reflect the way the world really is. If they seem to be emphasizing those aspects of life normally suppressed or censored as subversive, contentious, disturbing or too sexual, it is because that suppression is a deliberate attempt to limit the knowledge of the individual. It is our belief that truth and information about anything and everything must be made available in every way possible, if human history is to survive, progress or have any meaning whatsoever.13

In this polemical artist statement, we can see how P-Orridge views video collage as a way of forcing people to think about the images they consume. For h/er, television signals are a raw material and they can be used in order to think through and reveal ideas that are normally censored and suppressed. Throughout the four-hour long First Transmission we are repeatedly reminded of the adage: “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” In the context of footage that documents speeches by cult pastor Jim Jones, this pseudo-moralistic platitude seems as flimsy as any of the similar claims that appear at the beginning of most mondo films. Granted, the politics presented in Thee Grey Book are slightly more sophisticated and radical. It is a self-aware, ironic, anti-establishment doctrine that calls for its readers to think for themselves, to begin a journey of self-discovery, and to rebel against media control, conformity, and religious dogmas.

The First Transmission VHS was frequently traded, despite being originally advertised in Thee Grey Book, which was itself only available through Psychic TV’s mail order system in the early 1980s. Richard Metzger describes its origins:

[…] in defence of the project, Genesis told me that this material was more or less something that was conceived of to air on New York’s notoriously sleazy cable access station Channel J. The idea was for this weird, dreamlike footage just to appear on TV sets, sort of randomly, late at night, with no explanation whatsoever! 14

The tape itself includes various messages from “A Spokesman for Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth.” Although the tape is extremely violent, it is also playful. For instance, after a ritual involving cutting and scenes of bondage, sadomasochism, and simulated torture, there is a title card that reads “Intermission,” and before a section of the video featuring footage of Jim Jones and members of the Peoples Temple, a title card reads “Thank You Dad.”

Like most mondo films, First Transmission constantly blurs the line between fact and fiction —the central tension that delivers to audiences these works’ effect. One section is introduced with the title, “The following Polavision [an instant colour home movie system launched by Polaroid] footage was received via our contacts in San Diego, USA.15 The police department in that city claims to have no knowledge of the events that take place in this film.” The footage depicts older men cruising for young boys and a castration which, given the lo-fi nature of the footage, is nearly impossible to determine whether it is real. In 1992, another section from First Transmission was presented as evidence of satanic rituals when shown as part of BBC Channel 4’s Dispatches series. The allegations were serious enough to lead British police to raid P-Orridge’s home, forcing P-Orridge to flee the country, but the police found no evidence of satanic abuse. In recent years, some critics have argued that this coverage acted as a smokescreen for other, more legitimate offences.16

Just as it is possible to trace the influence of Ballard on SPK’s frontman Revell, it is possible to observe the influence of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin on P-Orridge. As scholar William Fowler asserts, P-Orridge “was a serious devotee of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin and regularly applied their techniques and ideas in new, unusual ways.”17 This is reinforced by the fact that Gysin is featured with one of his dream machines in First Transmission. Whereas Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition can be read as a metaphor for the collage video, Burroughs was equally cryptic while still directly addressing the medium. For instance, in his 1970 book The Electronic Revolution, Burroughs expands his cut-up technique beyond words by theorizing about its application to moving images. He argues words and images are a virus that can be used to infect people to change.

The cut-up technique can be traced to the Dadaists and was popularized by Burroughs and Gysin who applied it to print media and audio recordings. With experimental/horror filmmaker Antony Balch, Burroughs would import the idea to film when they collaborated on The Cut-Ups (1967), a movie quite radical in form at the time of its release (allegedly many people found the film to be “disorienting” when it was first shown at the Cinephone).18 Somewhat ironically, it is now more interesting due to its content, a time capsule of Burroughs visiting New York, London, and Tangiers in the early 1960s.

The British video art movement Scratch Video took Burroughs’ cut-up methodology to the extreme. Video artist George Barber, founder of the movement, claims journalist Pat Sweeney coined the term in 1984; however, the foundations were already set when Andy Lipman ran a City Limits feature story on it.19 According to Lipman, “Scratching is so simple. Just playing with the TV remote-control console, quickly switching stations at random, is a basic search. What emerges isn’t just a jumble of voices and images but the personality of broadcast TV itself. Its self-importance, its hectoring, its banality and plastic smile.”20 As the VCR offered new ways to engage with mass media, most users did not use their machines for this purpose. As media scholar Lucas Hilderbrand argues, “the availability and convenience of pre-recorded movies on tape drove the most publicized uses of home video away from recording toward renting, and consumers had to go to different types of stores to buy a deck and to rent movies.”21

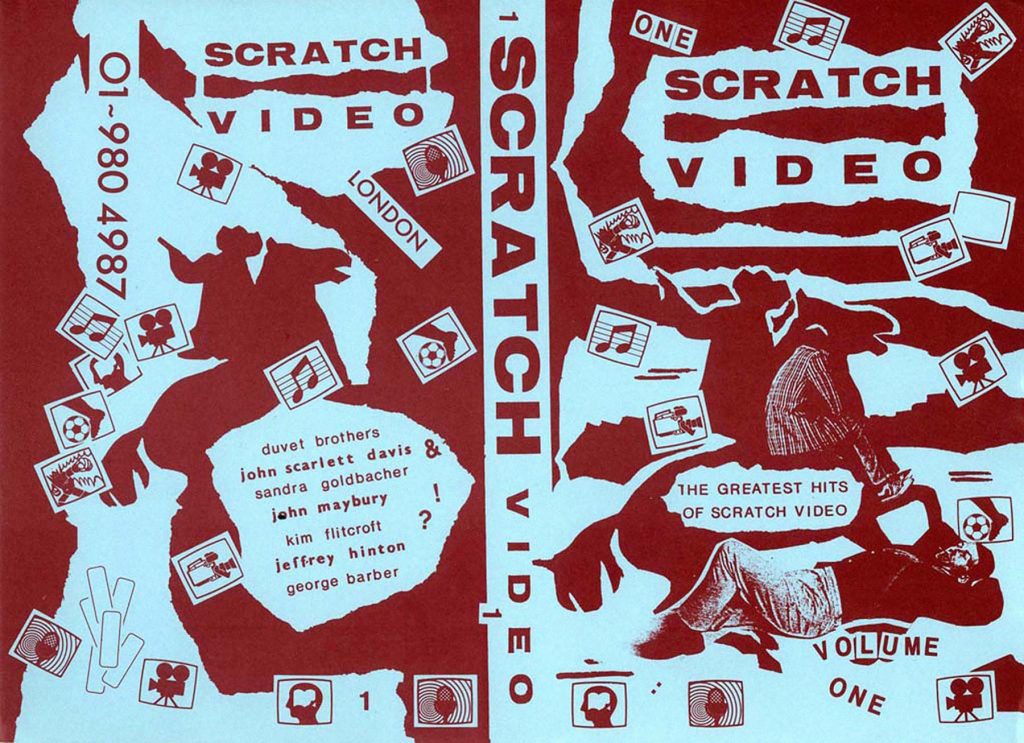

The Scratch movement originated in a nightclub called The Fridge, where London-based French artist Bruno de Florence set up twenty-five linked televisions, stacked on top of each other and spread around a dance floor. This became the setting of bi-weekly video screenings.22 As Barber explains: “At its best for about seven months, various makers would turn up with their latest work and sit around while a sizeable crowd—who’d probably never even heard of independent videos—watched their handiwork on banks of old DER monitors, some upside down, some even, artistically of course (what else?), on the blink.”23 In 1984, Barber released an independently distributed video mixtape titled The Greatest Hits of Scratch Video Vol. 1, with a second volume released a year later.

In addition to Burroughs’ influence, the Scratch movement—as its name suggests— also took inspiration from the sampled material and scratching of vinyl records by hip hop DJs. Moving beyond shock for shock’s sake, yet still incorporating graphic images of war and other transgressive audio-visual material, the works are diverse and often incorporate humour, irony, and political critiques. The videos are experimental and blend industrial post- punk with anti-Thatcher sentiment, allowing the work to fit comfortably both in an art gallery and at the nightclub.

It isn’t surprising that the birth of the video mixtape occurred at a time when home video editing and duplication was becoming available to the masses:

‘What do you want to watch on TV tonight?’ asked a VCR advert at the turn of the 1980s. It was precisely this question that new, young independent film and video makers, plus members of the counterculture, sought not just to exploit, but explore. They tested its personal and political ramifications, and pushed people’s limits as they went, bending identity and challenging straight Christian patriarchy.24

The VCR transformed the ephemeral television signal into something that could be contained, providing the consumer with a means to transform into a producer. At around the same time, industrial music entered the scene. In 1983, Vale wrote: “there is no strict unifying aesthetic, except that all things gross, atrocious, horrific, demented, and unjust are examined with black-humor eyes. Nothing is (or ever again will be) sacred, except a commitment to the realization of the individual imagination.”25 It is from these aesthetic conditions that the video compilation arose.

Budd Dwyer Exits, Entering the Scene

While the British industrial music scene generated mixtapes rife with gore-out shock clips and media deconstruction, the US parallel oeuvres were exploring televisual ephemera and pop culture, adding a distinctly anti-Reaganite attitude to their compilation aesthetics, beginning in 1986 with Cathode Fuck by Chris Gore and its sequel released a year later, TV Sphincter. In film critic Dave Carter’s history of the video mixtape, “The Television Screen is the Retina of the Mind’s Eye,” he explains that the structures of these two tapes “are the same and represent the blueprint of the video mixtape format.”26 These two mixtapes, as well as AMOK Assault Video (1988), would influence many of the mixtapes to come while also containing some of the elements of the video compilations that preceded them.

Cathode Fuck is compiled from performances by British punk bands The Clash and Public Image Ltd., in addition to other audio-visual material that was difficult to find at the time. The mixtape also features distinctly American footage such as scenes of moral outage culled from sensational daytime television, Chuck Norris on The Phil Donahue Show, scenes cut from an exploitative documentary on neo-Nazis in California titled The California Reich (1975), a series of poorly produced instructional videos that were sadistically intended for the eyes of McDonald’s employees, a video catalogue for bomber jets produced for the US government, and other rare gems. The video is structured like a mondo film about punk rock culture, but without any voiceover. In contrast to mondo documentaries, which played fast and loose with the truth, video compilations offer a form of meta-truth, a reflection on media saturation and a world of images where sensationalism is becoming the norm. As Goodall asserts, “much of today’s media output owes a debt to the aesthetics and politics of the mondo film.”27 Goodall’s statement seems to overestimate the influence of mondo film, but Cathode Fuck demonstrated that it was possible to create an exploitative and sensationalist documentary simply by turning on and recording the television.

Most video mixtapes are engaging in a form of copyright infringement. In this sense, a section of Cathode Fuck could be seen as a formal critique of such. Made ten years before Keith Sanborn’s slightly more academic video The Artwork in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility by Walter Benjamin as told to Keith Sanborn—a short video compilation from 1996 featuring FBI warnings accompanied by the borrowed muzak of Enoch Light—Cathode Fuck compiles various versions of the Warner Bros. logo while a live bootleg version of The Clash’s “Should I Stay or Should I Go” plays in the background. The video may simply have been added to accompany the rare musical tracks, but it can also be read as a playful nod to its own copyright violations.

In reference to AMOK Assault Video and Video Macumba (Mike Patton, 1991), independent horror film director Andy Copp asserts, “two VHS mixtapes in particular are the true Granddaddies of the movement and deserve some overdue recognition for not only the wild variety of clips chosen, but for their influence over the genre, and for getting there first.”28 There is some crossover between the tapes, including the famous footage of Pennsylvania state treasurer Budd Dwyer shooting himself during a press conference. Given that Chris Gore released TV Sphincter in 1987, it is quite likely that it is one of the first tapes to incorporate this footage. Dwyer’s public suicide became a staple of the more extreme video collages. On the AMOK Assault Video tape, it is sandwiched between footage of apanese men discussing the honour of taking one’s own life and televangelist Tammy Faye Bakker talking about being alone in a world without Christ, a cynical juxtaposition of ideas that one would expect to find in a mondo film.

Patton’s compilation Video Macumba is similar to SPK’s Despair in that there is no real narrative or underlying structure, just a collection of sadism, sex, and violence—a true audio-visual assault. As Dave Carter accurately observes, “the exclusively extreme mixtapes are intended not for titillation purposes but for shock value.”26 However, Patton’s mix also contains original material: the banned music video for Mr. Bungle’s “Travolta [Quote/UnQuote]” directed by Kevin Kerslake and skits starring Patton himself in a clown costume, morbidly re-enacting Dwyer’s suicide. A celebration of depravity, Patton’s tape wasn’t necessarily meant for consumption by the general public given that it was a homemade video given to three people: João Gordo of Ratos de Porão, Max Cavalera of Sepultura, and Priscila Farias of Animal magazine.29 This is the nature of the bootleg.

Psychic TV alumni Peter Christopherson would later go on to direct the infamous, never commercially released, but heavily bootlegged Broken VHS (1993), featuring music videos for Nine Inch Nails that were stylistically edited to resemble a video mixtape. Broken shares many aesthetic similarities with First Transmission, including what looks like a re-enactment of the cruising scenes in First Transmission. While discussing NIN’s bootleg Broken VHS, Christopherson observes that “because everyone was making bad dubs of bad dubs, what I considered at the time to be pretty obvious clues that this was a fake (and actually making a comment about those things) were lost by the bad quality. So unfortunately a lot of people, especially kids, started to believe that it was a real snuff movie.”30 Even NIN frontman Trent Reznor thought the tape had “crossed over into territory that was perhaps too far;” however, not far enough to stop him from giving a few copies to friends.30 Apparently each tape he distributed had its own unique dropout and tape errors to quickly identify whoever leaked it which, by the very nature of the bootleg, it did.30

Like many of the extreme images found in these types of compilation videos, it can be argued that the visually and sonically degraded nature of the material makes it more shocking. As media theorist Laura Marks has argued, “part of the eroticism of this medium is its incompleteness, the inability to ever see it all, because it’s so grainy, its chiaroscuro so harsh, its figures mere suggestion.”31 That is, its graininess leaves us with a mere impression and the viewer is invited to fill in the gaps and to engage with the fragments.

Artist Jonathan Price makes a similar argument about the seductive nature of video pornography. He suggests “that the effect of degraded video is like a striptease: Now you see it, now you don’t. And your imagination will inflame you more than a realistic picture could.”32 Hilderbrand continues this argument, clarifying that there is a connection between the aesthetics of a degraded VHS and the act of viewing forbidden material: “These blurry bootlegs foreground duplication and remind viewers that they are indulging in a pleasurably transgressive viewing act.”33 The act of remixing media brings the artist closer to it. By tracking down rare material, the mixtape creator puts on display their commitment to underground culture. The more difficult the object is to track down, the further away from the mainstream it lies. Mixtapes are made by individuals who see past the media’s facade and who are ready and willing to reveal, both their own superior tastes and the fact that the absurdity of mainstream culture.

Filth Tape Meets Zine Culture

AMOK Assault Video was compiled and distributed by Amok Books, an L.A.-based bookstore committed to outsider and kooky literature; and Cathode Fuck and TV Sphincter were released by Chris Gore, founder of the magazine Film Threat, one of the places in which mixtapes were first advertised. Carter claims this is “more than a simple coincidence,”26 arguing that compilation videos are connected to underground film and zine culture and to the tape-trading market that many early zines helped facilitate, especially in an era before the accessibility of everything via the Internet. In addition to promoting video mixtapes, Film Threat would also occasionally review mixtapes. One in particular stands out: a review of Winnipeg video collage artists Sebastian Capone and Richard Altman’s Sociology 666 (1996) by film critic Merle Bertrand. He complains:

Copying your film or video onto a used tape is tacky…but understandable. Tape IS cheap, but recycling tapes can save a starving filmmaker a few not-insignificant hundred dollars. Yet, Sebastian Capone and Richard Altman certainly didn’t earn any bonus points by sending in their tape in the condition we received it: sleeveless, the words “Filth Tape #1” scrawled in pen on a half peeled-off top label, and the ever-popular “666” chicken-scratched on the spine label. This is more than just a cosmetic beef. I literally don’t know what to call this damned thing.34

Despite criticizing the filmmakers’ lack of professionalism and praising the “sheer amount of research and time required to accumulate the mass of obscure clips,” Bertrand implies the tape itself isn’t “pleasant or interesting to watch.”32 However, from his review it is clear that he was only engaging with the work on a superficial level.

Sociology 666 is equal parts mass media critique and juvenilia, inspired as much by Marshall McLuhan as by Craig Baldwin. The video collage is divided into six sections: “Violence,” “War,” “Drugs,” “Surrealism,” “Carnage,” and “Sociology 666.” Most of the clips are taken from films and cable television, but the tape also includes some footage recorded by Capone and Altman, in particular, a scene that begins with the filmmakers reciting a McLuhanesque line, which seems to be the impetus for the tape itself: “Deconstruction of the message begins with the destruction of the medium.” After this line is uttered, the filmmakers proceed to smash televisions. To take this reading literally, as Bertrand does, misses the point since the entire film is a form of media deconstruction.

The main section, “Sociology 666,” uses a paranoid tone similar to Baldwin’s Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1991). But whereas Baldwin recompiles clipped 16mm films, Capone and Altman do so using cable television. The video collage uses a non-stop barrage of found footage from the fringes of popular consciousness to address problems of post-industrial consumerism in the forthcoming age of the World Wide Web. The video implicitly poses questions like: “How much of your privacy are you willing to give up for convenience?” Since that time, corporate surveillance has become a reality; but the video was made in an era before we clicked away all of our personal information in order to use an app or search the web.

The tape itself includes footage from AMOK Assault Video, documentation of Gysin’s Dream Machines from Balch’s Towers Open Fire (1963), and music by Mr. Bungle, Skinny Puppy, Psychic TV (including the Jonestown recordings used in First Transmission), and Nine Inch Nails, firmly planting the collage in the lineage of the mixtape back through its industrial roots. To its credit, Sociology 666 does avoid using the Dwyer footage, which was already cliché by that point. At the end, the film includes a long list citing all the sources, flexing its fair-use muscles.

Everything is Available, Everything is Terrible

Starting in the 1990s, hundreds of cable stations fought to fill their allotted airwaves; nevertheless, many people complained that there was nothing on television. People were at the mercy of television programmers. The VHS allowed people to capture moments from television that at one time would have been ephemeral, either you were watching it or you missed it. It was an era of media saturation and the beginning of the 24-hour news cycle. Even though media was abundant, specific media—especially works that were made on the fringes—was rare and required research to track down. As Rob Sheridan, an art director for NIN who remembers finding a copy of the infamous Broken VHS in his youth explains: “Kids today can’t possibly appreciate the feeling of tracking down a rare video artifact, because everything now is a mere Google search away… [Broken] was never meant for searchable, on-demand access, never meant for the soft-hearted masses who put no effort into seeking it out.”30

The desire to share the rare, to showcase and compress the best, the worst, and the most bizarre of what media has to offer into a disorienting assault on the senses and the sensible, is one of the underlying methodologies of the mixtape. A few of the first artists to celebrate the odd and the bizarre were TV Carnage (Pinky Carnage a.k.a. Derrick Beckles), The Show with No Name (Charlie Sotelo and Cinco), and 5 Minutes to Live (a now defunct bootleg distribution company that produced Lost & Found Video Night). With a focus on bizarre home movies, amateur videos, celebrities malfunctioning, lunatic television evangelists, and material recorded from public access television, this was a break from some of the previously established genre conventions—in particular, a move away from the grotesque and the extreme.

Lost & Found Video Night is still being produced and is now made available through streaming where it was originally distributed on DVD-R. It is an extensive collection, with over twenty volumes produced since 2003, which Carter argues is “the encyclopedia of the video mixtape genre, containing almost every notable clip that exists. […] Lost & Found best exemplifies the ‘party tape’ aspect of mixtape culture, as it can be watched in segments, contains little post-editing, and is a narrative-less collection of oddities.”26

Although The Show with No Name was not a mixtape, it was made in the same spirit. It was a popular public access television show in Austin, Texas, that ran from 1996 to 2005 and brought bizarre moments of video history to Austin’s general public, accompanied by commentary by the hosts and telephone calls from the audience.

In slight contrast, TV Carnage—which made its first mixtape Ouch, Television My Brain Hurt in 1996—produces compilations where each clip is carefully selected for being humorous, cringe-worthy or simply bizarre, while also providing social and cultural commentary. For instance, there are sections in TV Carnage’s A Rich Tradition of Magic (1998) that play with culturally insensitive jokes. In one section, radio personality Howard Stern plays “Rates the Races” with the former Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon (American white supremacist Daniel Carver) complete with a “race hierarchy” in “the vernacular of the KKK.” This and other scenes involving racist humour are intercut with a scene of Marvin “Smitty” Smith, the drummer from The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, hitting a bass drum and laughing. Such a montage reveals and undercuts the underlying racism in the source material by using an unsettling form of meta-humour. A Rich Tradition also demonstrates some of the absurd ways in which both underground and Black culture have been co-opted by consumer culture. For instance, a figure skater performs in a grunge costume to Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and actor Brian Austin Green attempts to rap on the Beverly Hills 90210 television drama series. Both Lost & Found and TV Carnage present the clips without voiceover. On a side note, newer TV Carnage DVDs have the option for commentaries, which are often as insightful as they are hilarious—in particular, the two commentaries for When Television Attacks (2000) performed by Beckles intoxicated by Canadian beer for one and by that watery substance some call American beer for the other.

Continuing in the tradition of Lost & Found Video Night are the collectives that form the Found Footage Festival and Everything is Terrible! In 2004, Joe Pickett, Nick Prueher, and Geoff Haas founded the Found Footage Festival, a compilation of home movies, amateur videos, and material recorded from public access television, all presented with research into the production history of the videos shown accompanied by comic banter. The focus of the Found Footage Festival is specifically on video oddities, and Pickett and Preuher have even released a book titled VHS: Absurd, Odd and Ridiculous Relics form the Videotape Era showcasing covers from their favourite second-hand VHS tapes. In the intro, they discuss the Golden Era of VHS, 1988–2008 (the year when “the last supplier of new VHS tapes unceremoniously shipped the last of their supply”), suggesting that “the VHS format was so ubiquitous, so affordable, and so easy-to-produce, that anybody with a pulse, a camcorder, and a few bucks could make [their] own video.”35 Found Footage Festival did research into the tapes they showcased, respecting the content while still making fun of it and acknowledging its absurdity.

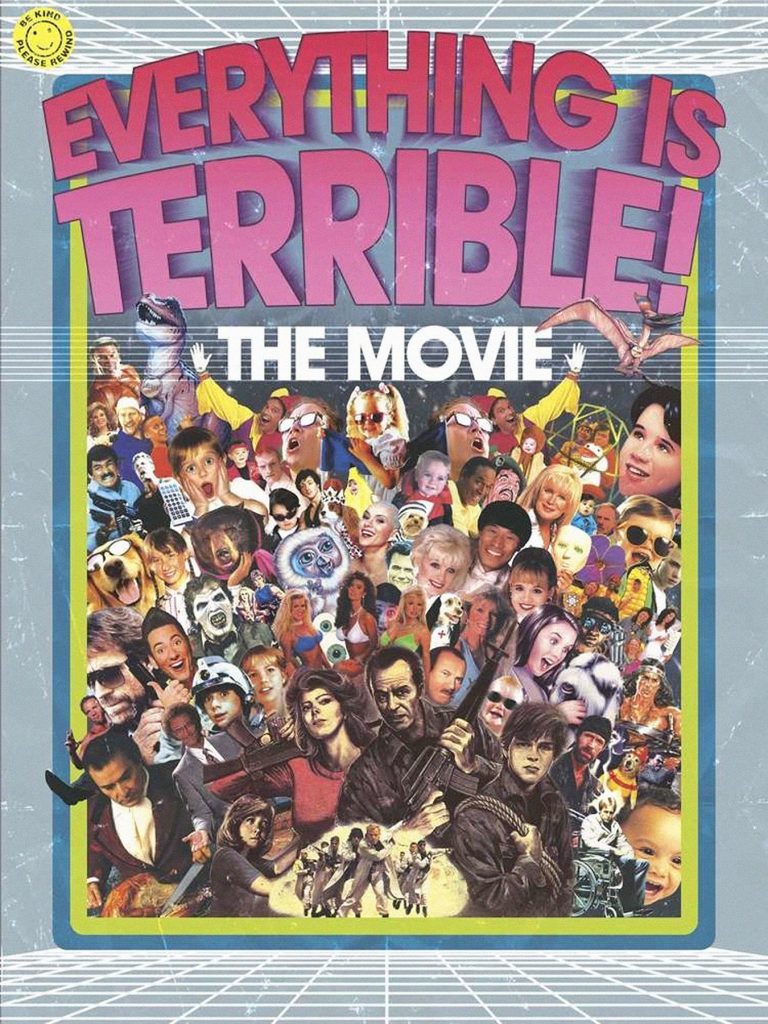

Everything is Terrible! is an artist collective based in Los Angeles that collects rare VHS tapes in order to produce their own entertaining remixes. In addition to their gathering of VHS curiosities, they also have the largest collection of Cameron Crowe’s magnum opus Jerry Maguire (1996) on VHS, which they have used to create the Jerry Maguire Video Store, an art installation at iam8bit Gallery in Los Angeles that looks like a 1990s-style video ental store with 14,000 VHS copies of the tape and other Jerry Maguire related ephemera. Unlike many other mixtape producers, Everything is Terrible! often re-edits the clips themselves, in addition to adding their own visual effects. In 2009, they released Everything is Terrible! The Movie which features their own remixes, and they’ve toured extensively with their work. They even created a shot-by-shot re-make of The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)—once a holy grail for cult film enthusiasts, made using only found footage of animals, titled Doggiewoggiez! Poochiewoochiez! (2012). Their work is humorous and engages with media literacy. The footage they work with is often unsettling not because of its graphic content, but because of its bizarre nature.

One of the more popular mixtapes is Retard-O-Tron Video Mixtape (2005), a party tape produced by ZXQL3000 (Roelewapper) and Cinema Sewer (Robin Bougie), now on its third volume.36 Retard-O-Tron was initially available on DVD and has subsequently been released by the makers on P2P networks, despite most of the material being captured from VHS. The compilations, like the name implies, are offensive and juvenile, and intend to both gross out and shock the audience. They have also allegedly been banned in the US, Canada, and Ireland.37 On their website, ZXQL3000 and Cinema Sewer provide a guide on how to make your own mixtapes, which includes the following methodology:

Be it home-shopping channel and cable access bloopers, disgusting scenes from sleazy splatter movies, amazing news footage, bizarre pornography, strange homemade video projects, extreme sports, disasters and mishaps captured on film, or foreign television gone mad—there has never been a set criteria for the footage that these video geeks collect— except that it should glue any eyes in the room to the TV screen in total amazement! […] The point behind which being […] not to make money, but to entertain fellow video-geeks by mixing up your own deranged cocktail of strange audiovisual shit from your personal collection, and sharing it—copyright laws be damned!38

Moreover, Retard-O-Tron is connected to zine culture through Cinema Sewer, which also helped to ensure an audience for their compilation.

VHS was an accessible format for the amateur television and media archivist, which is perhaps why the discolouration and signal dropout of video that has been recorded off television feels nostalgic in nature; it not only time shifts the television program, but it time- shifts us back to the moment of the recording, especially in an era of high-quality recordings. Moreover, during that era, there were many amateur productions that were distributed in small batches on VHS, further accentuating the medium’s amateur feel. Of course, this is part of its charm, but it also added to its authenticity. Granted, the amateur status of VHS might be one of the reasons mixtapes struggle to be taken seriously as art.

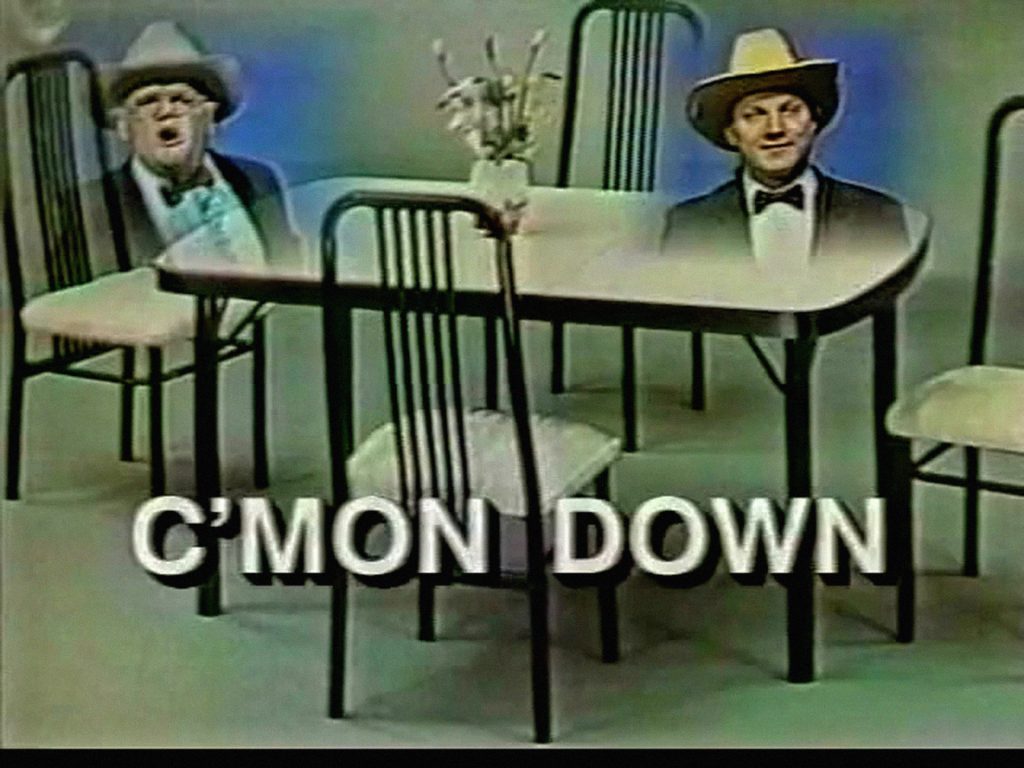

Kubasa in a Glass: The Strange World of the Winnipeg Television Commercial (1975-1993), made in 2005 by art collective L’Atelier national du Manitoba (Matthew Rankin and Walter Forsberg), is a video mixtape consisting of remixes of low-budget, regional television commercials. Interested in camp aesthetics and often employing a humorous editing style similar to Jeffrey Hinton’s contribution to Greatest Hits of Scratch Video, Kubasa in a Glass shares the curatorial best of the best hubris found across most earlier examples of the video mixtape practice; however, its objectives are notably different. While Hinton attempts to humorously deconstruct television commercials, L’Atelier national earnestly endeavour to preserve it—in all its camp glory—for history’s sake, arguing that “these exotic artifacts of Winnipeg commerce are lucid and highly expressive transmitters of this obscure Prairie city’s most profound and misunderstood secrets.”39 The opening lines of an artist statement for the video declares, “the purest form of Winnipeg national cinema is to be found within the disposable filmmaking of the city’s televisual ephemera,” later suggesting that “Kubasa in a Glass constructs a parallel history of Winnipeg through the prism of its bizarre and time-ravaged VHS ephemera.”40 In addition to being weird, the program holds a certain nostalgia for a time when television commercials were produced by local businesses for local audiences. Furthermore, the time-ravaged VHS contributes to feelings of nostalgia.

Conclusion

Television is at its core a one-way mode of communication. At its prime, it was a central component of consumer capitalism. The medium was a key force in the indoctrination of the masses, producing insatiable consumer desires that further contributed to an era of radical alienation. With the advent of the VHS, media consumers could transform themselves into media producers at the push of a button. However, the video mixtape as a practice has superseded the physical VHS tape format. For Retard-O-Tron it was P2P and DVD; for TV Carnage and Lost & Found Video Night, it was DVD-Rs and more recently streaming; for Kubasa in a Glass it was theatrical screenings; for Show Without A Name it was, somewhat ironically, public access television; for the Found Footage Festival, it was a live event; and in its most sanitized form, it has became YouTube, where (unless its conservative user agreements change) you will never be able to find the footage of Budd Dwyer’s suicide. By returning to these mixtapes in an era of mass connectivity, it is possible to see that part of the impetus for creating these videos was born out of a desire to reclaim media, for consumers to make it their own. Video mixtapes are both a celebration and a meta-critique, a way for individuals to both laugh at and be shocked by the grotesque and cringe-inducing by-products of a culture gone mad.

- Andy Copp, ‘‘I Wish I’d Taped That’: The Original Underground Compilation Videos,’ Cinema Sewer, no. 23 (April 2010): 12.

As Robin Bougie humorously writes of the early 1990s mixtape trading scene, “it was clearly mostly populated by lonely virgins living in their parents’ basements—with only two VCRs to use as equipment on which to create their VHS ‘masterpieces’.” [↩] - Mondo films are exploitative documentary films known more for their sensational depictions of foreign cultures or emphasis on the taboo than for their accuracy. Shockumentaries are graphic documentaries that deal with the topic of death and violence in a sensationalized and shocking manner. For more, see: David Kerekes and David Slater, Killing for Culture (London: Creation Books, 1994) and Mark Goodall, Sweet & Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Film Lens (London: Headpress Books, 2006). [↩]

- V. Vale and Andrew Juno, “Introduction,” in J. G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition (San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, 1990), 6. [↩]

- Rob Tannenbaum and Craig Marks, I Want My MTV: The Uncensored Story of the Music Video Revolution (New York: Penguin, 2012), 40. [↩]

- Graeme Revell, “Close to the Heart,” Sounds (December 24, 1983). [↩]

- Thomas Frick, “The Art of Fiction No. 85,” The Paris Review 94 (Winter, 1984). [↩] [↩]

- E-mail correspondence with Graeme Revell in February 2024. [↩]

- Mark Goodall, Sweet & Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Film Lens (London: Headpress Books, 2006), 13. [↩]

- Mark Goodall, Sweet & Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Film Lens (London: Headpress Books, 2006), 14. [↩]

- Mark Goodall, Sweet & Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Film Lens (London: Headpress Books, 2006), 25. [↩]

- David Kerekes and David Slater, Killing for Culture (London: Creation Books, 1994), 170. [↩]

- David Kerekes and David Slater, Killing for Culture (London: Creation Books, 1994), 172. [↩]

- Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, “Thee Grey Book,” in Jason Louv (ed.), Thee Psychick Bible (Port Townsend: Feral House, 2009), 52. [↩]

- Richard Metzger, “PTV’s Infamous First Transmission Underground Video,” Dangerous Minds (May 2, 2013). [↩]

- For more on Polaroid’s Polavision see: Erika Balsom, “Instant Failure: Polaroid’s Polavision, 1977–1980,: Grey Room 66 (2017): 6–31. [↩]

- Dan Siepmann, “Groupthink and Other Painful Reflections on Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth,” Pop Matters (September 27, 2019). [↩]

- William Fowler, “The Occult Roots of MTV: British Music Video and Underground Film-Making in the 1980s,” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 11.1 (Spring 2017): 71. [↩]

- “Roy Underhill, the assistant manager at the time, told Balch that during the performances an unusual number of strange articles such as bags, pants, shoes, and coats were left behind, lost property, probably out of complete disorientation.” See: Rob Bridgett, “An Appraisal of the Films of William Burroughs, Brion Gysin, and Anthony Balch in terms of Recent Avant Garde Theory,” Bright Lights (February 1, 2003). [↩]

- George Barber, “Scratch and After: Edit Suite Technology and the Determination of Style in Video Art,” in Philip Hayward (ed.), Culture, Technology, and Creativity in the Late Twentieth Centure (London: John Libbey, 1990), 116. According to Barber, Sweeney was “comparing it to New York’s Hip Hop scene,” hence the label scratch. [↩]

- Andy Lipman, “Scratch and Run,” City Limits (October 5–11, 1984): 19. [↩]

- Lucas Hilderbrand, Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 55. [↩]

- Nick Cope, “Scratch Video,” Nick Cope Film (September 17, 2013). [↩]

- George Barber, “Scratch and After: Edit Suite Technology and the Determination of Style in Video Art,” in Philip Hayward (ed.), Culture, Technology, and Creativity in the Late Twentieth Centure (London: John Libbey, (1990), 114. [↩]

- William Fowler, “The Occult Roots of MTV: British Music Video and Underground Film-Making in the 1980s,” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 11.1 (Spring 2017): 65. [↩]

- V. Vale and Andrea Juno, Industrial Culture Handbook (San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, 1983), 2. [↩]

- Dave Carter, “The Television Screen is the Retina of the Mind’s Eye,” Not Coming to a Theatre Near You (May 4, 2010). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Mark Goodall, Sweet & Savage: The World Through the Shockumentary Film Lens (London: Headpress Books, 2006), 8. [↩]

- Andy Copp, ‘‘I Wish I’d Taped That’: The Original Underground Compilation Videos,’ Cinema Sewer, no. 23 (April 2010): 8. [↩]

- João Gordo, ‘As taras secretas de Mike Patton,’ Bizz no. 82 (May 1992): 22. In 1994, Ratos de Porão released a song about the video titled “Video Macumba.” [↩]

- Tim Grierson, “Nine Inch Nails Broken Movie: Story Behind the Infamous Viral VHS ‘Snuff Film’,” Revolver (September 19, 2017). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Laura Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 11. [↩]

- Jonathan Price, Video-Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself (New York: New American Library, 1977), 216. [↩] [↩]

- Lucas Hilderbrand, Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 180. [↩]

- Merle Bertrand, ‘Sociology 666,’ Film Threat (September 6, 2000). [↩]

- Joe Pickett and Nick Prueher, VHS: Absurd, Odd, and Ridiculous Relics from the Videotape Era (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2011), 4-5. [↩]

- Robin Bougie has been producing mixtapes since the 2000s, beginning with The Atom Strikes (2000), which screened at the Blinding Light Cinema in Vancouver, BC on August 25, 2000. [↩]

- Andy Maxwell, “Prepare Yourself For Video Mixtape Month on The Pirate Bay,” TorrentFreak (June 9, 2009). [↩]

- ZXQL3000, “Make Your Own Mixtape,” ZXQL3000 (2006). [↩]

- Walter Forsberg, Starvation Years: Album de l’Atelier national du Manitoba (Winnipeg: l’Atelier national du Manitoba, 2014), 44. [↩]

- Matthew Rankin, “Note on Kubasa by Atelier national du Manitoba,” cineflyer (August 2012). [↩]