“Singing the Body Electric: An Interview with Dalibor Barić.” Spectacular Optical (September 27, 2013).

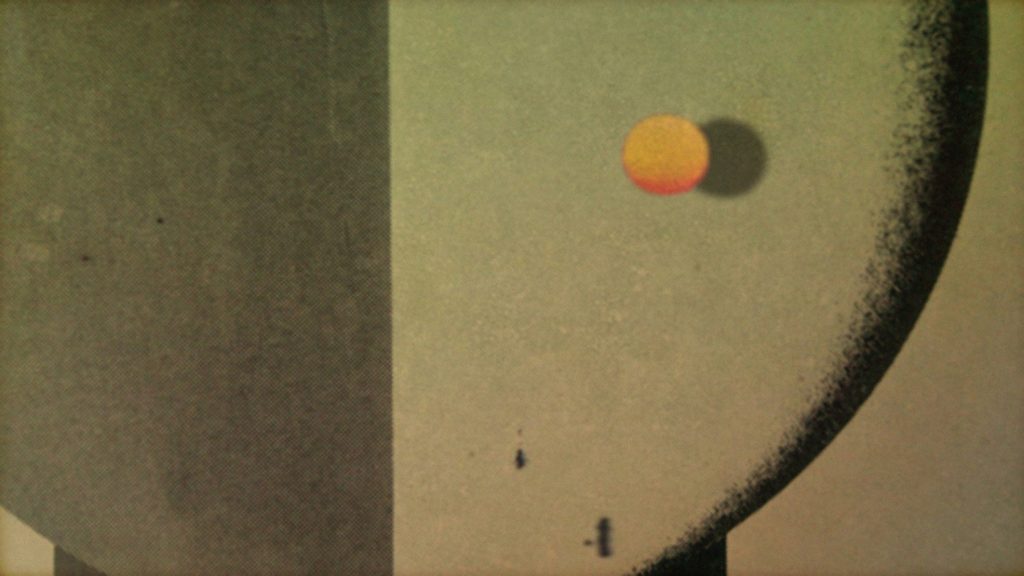

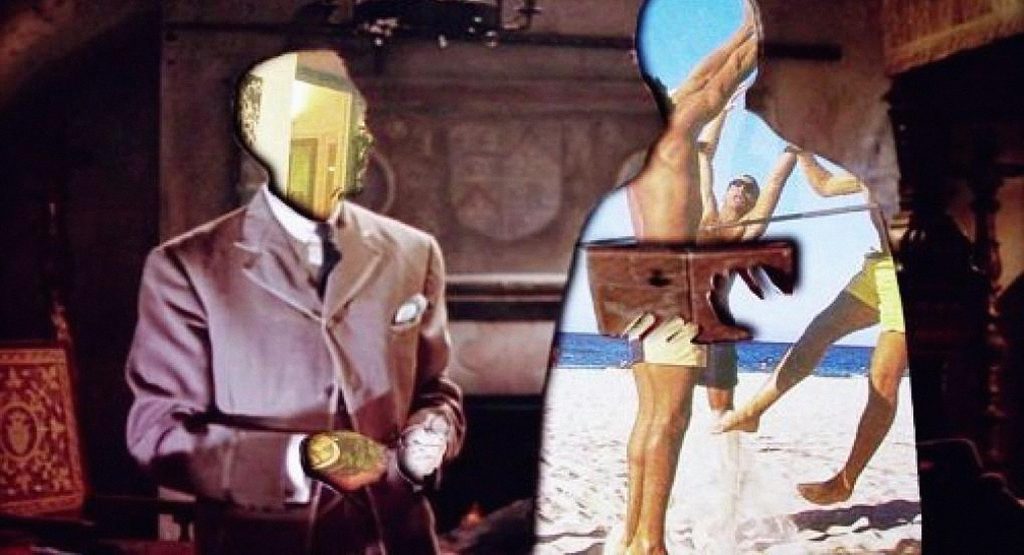

Dalibor Barić is a Croatian experimental filmmaker whose works often explores traditional genres like science fiction and horror. Using found objects as his source material, Barić uses collage techniques in order to produce sophisticated psychedelic narratives that often blur the lines between our outer and inner realities. Moreover, Barić’s work also calls into question issues surrounding artistic practices in the digital age including ideas about authenticity, simulation/replication and appropriation. With that being said, his work is extremely engaging, bizarre and stimulating.

The following is an interview with Barić that took place over many conversations via e-mail.

Clint Enns: Let us begin with one of the more obvious questions. How are your films made?

Dalibor Baric: For me, it all begins as child’s play; I wanted to be a filmmaker, but without worrying about budget and equipment. I am a ringleader for a flea circus comprised of found-footage, collage and references attempting to make films that examine various subjects. Unfortunately, it is impossible to avoid real work. Like a stowaway destined to peel potatoes, I work frame by frame making handmade films using a Wacom tablet and Photoshop.

CE: In your work you blur the boundary between still and moving images. For instance, you experiment with the boil (a short loop that creates the illusion of movement), the pan, the zoom, layering, rotating and flipping the image, etc.

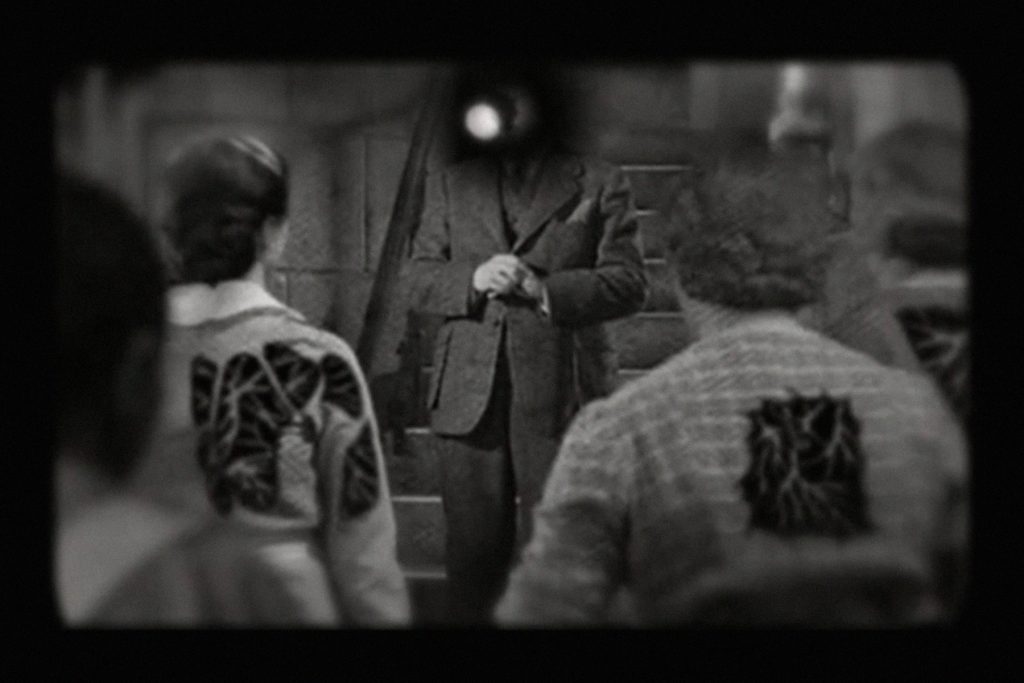

DB: There is a concept from the field of robotics called the “uncanny valley,” in which a CGI character becomes too realist producing a feeling of repulsion when humans look at it, in essence, describing the cognitive dissonance we feel when the illusion of the Real is disrupted. I like to create this kind of rupture by breaking the illusion of homogeneity and continuity in film, that is, to spoil the believable, realistic effect by bringing to surface all this mechanics of film which are supposed to remain hidden. In other words, the medium has of same importance as the message.

CE: Is your work digital or a hybrid form of film and digital?

DB: I never work with film, besides hand scratching on old 35mm stocks. In the end, it’s all digital, even though my source material is gathered from everywhere: scrap images, textures, photographs, re-shot sequences from a television or computer screen. I cut out each image free hand using Photoshop to emulate scissor paper cut-outs to achieve an organic atmosphere or daylight presence. I never use any of the built-in effects or plug-ins other than Gaussian blur and basic colour correction. I would rather invent an effect or technical solution instead.

CE: One of the most aesthetically apparent aspects of your work is the use of digitized film grain and other replicated filmic artifacts, like sprocket-holes, etc. What does authenticity mean in the digital age?

DB: There is an excellent example of forgery versus authenticity in Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in High Castle (1962). The book can be read as an exploration of Baudrillard’s concept of simulacra, a copy without an original, that is, pure simulation. I am fascinated by the way in which digitized old movies keep traces of mechanical damage and decay. It has all become merged in one layer, like a fossil. New digital artifacts are introduced through compression. Who knows, maybe the original film has already ceased to exist and this version is all we are left with. It’s a disturbing, haunting thought. Culturally, we are obsessed with the relics of our past. Think about our generations interest in retro, hauntology, fantasy, steampunk, Instagram, etc. Due to the internet, we are over saturated with the radioactive contamination of our past forcing the future to disappear along the way. It might have something to do with creating a peaceful anchor in time. These are some of the reasons I make digital films that mimic analogue ones. To document death in the rear-view mirror. “Watch out, the world’s behind you”, sings the Velvet Underground in Sunday Morning.

CE: You have nothing to worry about, the future is coming. Plus, as you have already pointed out, new technologies inevitably produce new artifacts which will eventually become nostalgic. I can image future generations saying, “Instagram 9.4 is terrible, do remember the original Instagram?” Do you feel the affects you create by simulating an effect are nostalgic in nature or something entirely new? Do you feel you are also expanding analogue techniques by simulating them through the use of a computer?

DB: Film itself is one the most technological-based mediums and the technology itself defines and structures its aesthetic. I don’t think that I’m creating something entirely new because what I’m doing is encoded in the aesthetic/technology inherent to the medium (frame, duration, camera, screen). However, I don’t see it as purely pastiche or repeating what has already been done. Still by doing this with new technologies we are definitely working towards something new. For instance, the technical process is much easier, faster, controllable, malleable, etc. In my case, it allowed me to produce many completed films in a very short time by myself, as if I was composing on a musical instrument.

CE: Your sound design is incredibly cinematic. Do you use the same processes as your image production?

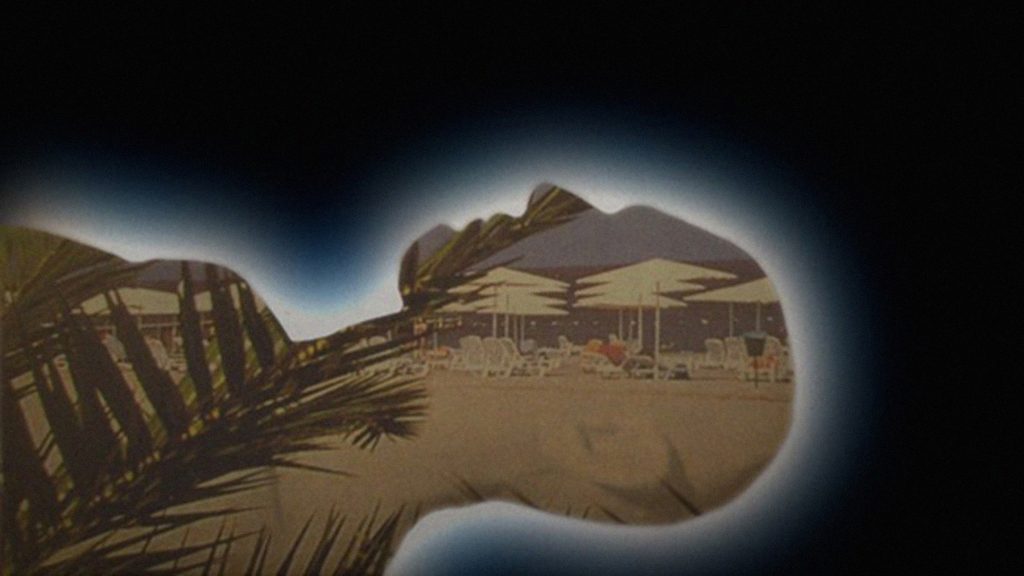

DB: For the most part, I do my own sound design using Fruity Loops. For Amnesiac on the Beach (2013), I worked with composer Tomislav Babić with whom I share the same interest for kraut rock/experimental music, the BBC radiophonic workshop, science fiction soundscapes, 70’s television and movie soundtracks. I should add that all my previous movies were made after the music/sound design, which set the atmosphere and dictated the visual rhythm of the films. Furthermore, these films were made rather quickly. I would regularly upload them to Vimeo, however, I do not consider them to be part of my filmography proper; rather they are make-believe films or exercises.

CE: Are you influenced by other experimental collage filmmakers? Marienbad First Aid Kit (2013) seems particularly Lewis Klahr inspired, both in your use of text and in your use of comic book images. Can you talk about your approach to collage in film?

DB: I think Martha Colburn’s work is amazing. I often visit her website looking for new work. Of course, Lewis Klahr is a major influence on my work. The first thing I saw by Klahr was a music video and it captured me. Since that time, I have attempted to read every interview and article on Klahr, however, until recently I have been unable to see any of his other films. At that time I could only speculate about the movement in his work. In a way, Marienbad First Aid Kit can be seen as an homage to Klahr, even the use of music which is Achille-Claude Debussy with the Forbidden Planet soundtrack. In addition, Marienbad First Aid Kit also connects to Alain Resnais’ L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961) which supposedly was based on La invención de Morel (Morel’s Invention, 1974) by Adolfo Bioy Casares.

The narrative, textual part of film, is composed from dozen of of comic books from Mandrake the Magician to various Marvel and DC comics. The visual imagery would take too long to mention it all. Marienbad is my first film after Amnesiac on the Beach which is my only funded project to date. Since I completed Amnesiac, I started several collage based films which I will never finish. I came to a dead end and felt I was starting to repeat myself so I gave up for a while. I have two upcoming projects: a short film called Unknown energies, Unidentified sensations and a rotoscopic SF animated movie Astronaut of Featherweight. Both have professional actors, film crews, small budgets, etc.

CE: Your work is constantly referencing other works from William S. Burroughs to J.G. Ballard, from genre films to the French New Wave, in essence sampling. Can you talk about the use of appropriation in your work?

DB: William S. Burroughs and J.G. Ballard were real discoveries for many reasons. For instance, they both combined experimental and science fiction. In addition, their writing techniques involved the surreal, the idea of inner space, contemporary landscapes, alienation, media theory, etc. The French New Wave also had this relationship with pop art, science fiction, literature, in addition to a radical approach to filmmaking. It was a very exciting and inspiring thing for me. I use many references, for example, the title you who exist only in the darkest recess of my own brooding mind, i command you-appear! (2010) comes from a Doctor Strange comic speech balloon whom I prefer more than Aleister Crowley. Furthermore, humour is important to me.

CE: Let’s talk about some the narrative devices you are using. For instance, how you externalize internal emotions. In Don’t you want to hear my side? (2010) the couples internal conflict seems represented by images of war and in Ghost Porn in Ectoplasm! But How?? (2010) inner most desires are represented by ectoplasmic outbreaks. Furthermore, what role does free association play in your work?

DB: I like to think of my films as ectoplasmic manifestations of our inner worlds. For me, film/video is a non-place between life and death, an idea I explicitly explore in Amnesiac on the Beach. For instance, my characters in Ghost Porn in Ectoplasm, But How?, Don’t you want to hear my side?, and The Spectres of Veronica (2011) are either vessels or possessed by forces unknown to them. They are oblivious of the nature or conditions of their existence. It also reflects my own view of reality. Humans are “strangers in the strange land,” possessed by consciousness, the mind from nowhere. In Amnesiac on the Beach, I was amused by the idea that due to nature of our minds and nervous system, every (interpersonal) communication is in fact a telecommunication; every contact with the outer world is a broadcast, an interpretation, just like a television.

About the process of my filmmaking, it is mostly intuitive and based on stream of consciousness with some real-time structuring. It walks the thin line between knowing and not knowing what goes next. It’s like Tarot readings.

CE: It seems the people in your films are always trying to transcend the body, both in terms of narrative and form. In some films it is spiritual and in others it is through technologies.

DB: Artistically, I’m interested in bodily effects, a special effect in which a body can produce doppelgangers, hauntings, possessed bodies, ectoplasmic bursts etc. I see the body as more than a mere vessel in which the real-self (or spirit) is placed, but something entwined and inseparable. Similar to our relationship with the places which surround us. Places structure our sense of self, for instance, they determine if we feel cozy, safe or alienated. I think on symbolic level there is a certain dualism between what we think of as the inner world of mind and outer world of everyday reality where our bodies represent a border; avatars in flesh, physically limited and vulnerability. Bodies are zones of conflict and transgression, of diseases and violence and I think this need of escapement, transcendence is a primal desire for self-protection and self-preservation, of having some hope that there is an escape pod; spiritual or technological, which return us back into some Cartesian point of view. People need their fantasies, beliefs and some amortization. Consider the painting by Surrealist artist Remedios Varo titled Embroidering Earths Mantle (1961) depicting captive maidens in the top room of circular tower, embroidering a tapestry which is falling out of the windows into the void. We see that everything in the outside world is made out of the same tapestry: cities, seas, forests and even the tower of their imprisonment. The whole world is tapestry and the tapestry is the world.

Interview de Dalibor Barić par l’artiste vidéaste et cinéaste, Clint Enns

“Interview de Dalibor Barić par l’artiste vidéaste et cinéaste, Clint Enns.” [Excerpt from “Singing the Body Electric With Dalibor Barić” translated into French by Nicole Morgan]. Traverse Vidéo, Exhibition Catalogue (Toulouse, France: 2014): 56-58.

Clint Enns : Commençons par l’une des questions les plus évidentes. Comment travaillez-vous vos films ?

Dalibor Barić : Pour moi, tout commence comme un jeu d’enfant. Je voulais être cinéaste, mais sans me soucier du budget ni du matériel technique. Je suis un peu comme un dresseur de puces savantes de cirque, qui avec des séquences vidéo, du collage et des références fait des films qui explorent divers sujets. Malheureusement cela n’annule pas du tout le travail à fournir et, tel un passager clandestin destiné à peler les pommes de terre, je travaille image par image, en un travail artisanal besogneux grâce à une tablette Wacom et à Photoshop.

CE : Vous floutez la frontière entre images fixes et images animées. Ainsi, expérimentez-vous l’approche, en une petite boucle, pour créer l’illusion du mouvement, par le panorama, le zoom, les plans successifs, la rotation, le retournement de l’image, etc.

DB : Cela vient d’un concept de la robotique, l’Uncanny Valley, par lequel un personnage d’image de synthèse devient si réaliste qu’il provoque un sentiment de répulsion. Ce concept décrit la manière cognitive que nous ressentons lorsque l’illusion du réel est perturbée. J’aime créer ce genre de rupture en brisant l’illusion d’homogénéité et de continuité dans un film, cela revient à altérer le caractère crédible, l’effet réaliste, en exhibant tous les mécanismes censés rester cachés. En d’autres termes, le médium compte autant que le message.

CE : Travaillez-vous en numérique ou sous une forme hybride ?

DB : Je ne travaille jamais avec du film autre que du vieux 35 mm sur lequel j’effectue un grattage manuel. En fin de compte, tout est numérique, même si la matière de base collectée provient d’un peu partout : de chutes d’images, de textures, de photographies, de prises empruntées à la télévision ou à l’ordinateur. Je découpe chaque image avec Photoshop pour imiter le papier découpé aux ciseaux et ainsi obtenir une « qualité » organique ou l’effet lumière du jour. Je ne retiens jamais l’un des effets intégrés au logiciel ou des plug-ins autres que du flou gaussien et la correction des couleurs de base. Je préfère inventer un effet ou trouver une solution technique qui me soit propre.

CE : L’un des aspects les plus esthétiquement visibles de votre travail est l’effet de grain-photo et la reproduction de techniques de film à l’ancienne, comme les perforations qui sillonnent une pellicule, etc. Quel sens donner à l’authenticité à l’ère du numérique ?

DB : Un excellent exemple de faux par opposition à l’authentique nous est donné par le roman de Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle de 1962. Le livre peut être lu comme une exploration du concept du simulacre de Baudrillard, d’une copie sans original, ce qui revient à une pure simulation. Je suis fasciné par la manière dont les vieux films numérisés conservent les traces d’altération et de dommages mécaniques. Ils ont laissé une empreinte, comme un fossile. Les nouveaux artefacts numériques sont introduits par compression. Qui sait, peut-être que le film original a déjà cessé d’exister et que cette version est tout ce qu’il nous reste. C’est une pensée à la fois obsédante et inquiétante. Culturellement, nous sommes obsédés par les reliques du passé. Penser rétrospectivement à l’intérêt de nos générations, à ce qui nous hante, l’imaginaire, le steampunk, Instagram, etc. À cause d’Internet, nous sommes absolument saturés par une contamination radioactive de notre passé, ce qui altère notre vision du futur. Ce qui peut mener à l’élaboration de signaux d’ancrage pacifique dans le temps. Ce sont quelques-unes des raisons pour lesquelles je fais des films numériques qui imitent l’analogique. Pour apporter un éclairage sur la mort comme si on la voyait dans un rétroviseur. Regardez, le monde est derrière vous, chante le Velvet Underground dans « Sunday Morning ».

CE : Comme vous l’avez déjà expliqué, les nouvelles technologies produisent immanquablement de nouveaux artefacts qui alimentent éventuellement la nostalgie. Je peux imaginer que les générations futures diront : « Instagram 9.4 est épouvantable, vous souvenez-vous du tout premier Instagram ? ». N’avez-vous en conséquence que vous développez des techniques analogues en les simulant sur ordinateur ?

DB : Le film-ui-médium est l’un des médiums qui utilisent le plus la technologie, la technologie définit sa structure et son esthétique. Je ne pense pas créer de l’entièrement nouveau, car ce que je fais est codé dans l’esthétique, la technologie inhérente au milieu : cadre, durée, caméra, écran. Cependant, je ne le considère pas comme relevant du pastiche ou du répétitif de ce qui a déjà été fait. Ce faisant, avec les nouvelles technologies, nous entraînons le travail vers de nouvelles perspectives. Par exemple, le processus technique est beaucoup plus facile, plus rapide, contrôlable, malléable, etc. Il m’a permis, précisément, de produire moi-même de nombreux films dans des délais restreints, comme si je composais sur un instrument de musique.

CE : Votre conception sonore est incroyablement cinématographique. La composez-vous avec les mêmes procédés avec lesquels vous composez les images ?

DB : Je crée le plus souvent mon propre fond sonore avec Fruity Loops, musique assistée par ordinateur. Pour Amnesiac on the Beach, de 2013, j’ai travaillé avec le compositeur Tomislav Babic avec lequel je partage le penchant pour la musique expérimentale telle que le Krautrock, l’atelier radiophonique de la BBC, les environnements sonores de science-fiction, les bandes sons des films et séries télévisées des années 70. Par ailleurs, tous mes films précédents ont été construits sur la base du concept musique/son, c’est-à-dire l’ambiance et dicte le rythme visuel des films, qui ont, entre autres, été réalisés plutôt rapidement. […] Pour Manneband First Aid Kit de 2013, fait référence à L’Année dernière à Marienbad d’Alain Resnais, de 1961. Je me suis également inspiré de L’Invention de Morel de 1974, d’Adolfo Bioy Casares.

CE : Parlons de certains de vos dispositifs narratifs.

DB : J’aime à imaginer mes films comme des manifestations ectoplasmiques de nos mondes intérieurs. Pour moi, le cinéma ou la vidéo sont un lieu imaginaire entre la vie et la mort, une idée que j’explore explicitement dans Amnesiac on the Beach. Par exemple, mes personnages de Ghost Porn in Ectoplasm, But How?, Don’t you want to hear my side? et The Spectre of Vovnia (2011) font allusion soit à des vaisseaux soit à des êtres possédés par des forces inconnues ; ils ne sont pas conscients de la nature ou des conditions de leur existence. Cela reflète ma propre vision de la réalité. Les humains sont des étrangers dans une terre étrange, possédés par la conscience, l’esprit ne lui parle pas. Dans Amnesiac on the Beach, imaginer qu’en raison de la nature de notre esprit et de notre système nerveux, chaque communication interpersonnelle n’est autre qu’une télécommunication ; que tout contact avec le monde extérieur est une diffusion, une interprétation, comme la télévision, m’a amusé.

Concernant le processus de ma technique cinématographique, il est principalement intuitif et fondé sur le flux de la conscience avec une certaine structuration en temps réel. Ce qui matérialise la ligne floue qui existe entre le savoir et le non-savoir et ce qui se passe ensuite. Cela ressemble à la lecture du Tarot.