“Quiet Anthems: An Interview with Eric Quach.” Whitehot Magazine (October 2025).

Eric Quach is best known as an architect of sonic assaults under the guise of thisquietarmy. His weapon, an electric guitar; his conquest, vast expanses of disintegrating soundscapes. He has released an avalanche of albums with an endless stream of collaborations, touring landscapes long forgotten by the industrial music machine. In addition to these textured sonic landscapes, Quach transforms his world into image.

In 2017, Quach unveiled Conqueror, a collection of frozen moments; photographs taken along the endless march of tours, a silent testament to his ongoing journey. The book promises “an anthropological glimpse” into Quach’s odyssey. Within its pages, his images hum with the pulse of decay, capturing landscapes haunted by their unseen histories. Black-and-white—raw and scarred, these photos are less a window and more a reflection of entropy, suspended in time. Accompanying this tome is a 7″ flexi-disc placing it somewhere between art book and band merch.

Like his music, his photographs are spectres caught in the collapse of a fading empire. You stand at the edge, looking out across the ruins of a world unravelling slowly, steadily. Everything feels suspended in the stillness of a forgotten moment, abandoned by time, haunted by absence. Each image is a distant echo buried beneath layers of dense noise, quiet anthems to a world that once was, a long-lost signal from another time.

This interview was conducted by e-mail and collaboratively edited into its current form.

Clint Enns: Your work resonates with a particular Montréal-ethos, especially in the aesthetics often linked to Constellation Records and the early 2000s music scene. I’m not suggesting that your art is rooted in the past or bound to a singular aesthetic from that time—but the echoes remain. How do you see yourself in relation to this scene?

Eric Quach: I am definitely a fan of Constellation Records and their DIY, anti-capitalist ethics. In the late 90s, everything “alternative” seemed extroverted, obnoxious, and narcissistic. Entering a loft where a small group of people were sitting in the dark listening to twenty minute songs played live made me aware of a whole other universe of art, sound, and aesthetics that were light-years away from the mainstream media. And this was within my own city. I could identify with the anti-rock, anti-theatrical, anti-hero attitude which opened up a new world of possibilities.

At that time, the division of Anglo and Franco music scenes was still very present. Constellation Records was mostly affiliated with the Anglo music scene, a hub for expat artists coming from various parts of Canada and the US. Being native to Montréal, I didn’t see the city as a cheap idyllic city full of potential with tons of abandoned space, but as remnants of a failed referendum now occupied by expats artists. They were starting their lives over in a city that didn’t rightfully belong to them, but that they made it their own—right under our noses while we were living deep into our own Montréal/Québec darkness, dramas, and disagreements: the economy was disastrous, the politics were awful, our sports teams were losing, our lives were depressing, and to make things worse…the Anglos weren’t acknowledging us. Yet, it wasn’t envy, it was a beacon of hope emerged in our unique island-city. It inspired us to create.

CE: What do you see as the influence of Montréal’s artistic landscape on your visual approach?

EQ: Working with Where Are My Records (which was affiliated with a francophone indie music zine called emoRAGEi Magazine) was particularly eye-opening. The label had a visual aesthetic more rooted in photography and landscapes which had ethereal, poetic, and melancholic qualities. The bands on the label were sonically less angry, more sensitive, more dreamy.

Destroyalldreamers approached Patrick Lacharité [from Below The Sea and WAMR’s graphic designer and audio consultant] to help us produce our first album, which was recorded in his home studio/apartment in the Plateau. We collaborated together on the design of the album. Beyond the graphic work, we used an ambiguous image to capture the absurdity of the album’s abstract title “À coeur léger sommeil sanglant,” [“Lighthearted Bloody Sleep”]—a cut apple wrapped in a thick brown string. This cover was a crash course in digital photography and graphic design.

CE: In the beginning, you captured moments through the lens of a simple point-and-shoot. As time passed, that device gave way to another which offers a different form of immediacy, the smartphone. Did this technological shift alter the way you saw the world through the frame? Did it change the way you took photos?

EQ: When I’m on tour I have a lot of equipment and I often travel alone, so the smartphone is a convenient tool to document and capture everything I am living through.

More than the camera, Instagram and social media have changed my relationship to photography. For instance, I went from posting single photographs to curating galleries which are able to express a story.

CE: The photographs in Conqueror are both diaristic and a stylized form of tourist photography, perhaps, tour-istic photographs, but they also feel estranged. Is it the hidden, unfamiliar histories that appeal to you?

EQ: I tour in order to perform music outside of Montréal. On the road, I like to be hosted since this provides an opportunity to see how other people live: their habits, their surroundings, their food, their interests, their politics. Meeting people from all walks of life who shares different perspectives but who share a common interest: music. What you call “touristy” is, to me, merely an attempt to catch a glimpse of another culture, another way of life, an opportunity to actually meet and get to know different people.

CE: Contemporary photography is often a way to simply relieve boredom or to distract from loneliness. Tourist photography is often a way to relieve some of the anxiety of being in an unfamiliar place, a way to mediate the experience, a way to distance oneself from reality. Do you see the act of taking diaristic photographs as a way to transform one’s life into a work of art or is it a way to relieve boredom/aniexity?

EQ: All photography captures a moment in time. Sometimes the photograph is of a monument or a piece of architecture that has been standing for centuries and sometimes the photograph captures a fleeting event, one that has only existed for a fraction of a second.

I often take a photograph in order to capture a feeling. In editing the photograph, I want to reveal the emotions that triggered me to take the photograph. The impulse, an electrical signal sent from deep inside, the awakening from a dead state, a desire linked to survival, an inspiration of hope, a stimulation of the senses. I am not necessarily trying to capture a faithful representation of the subject.

I don’t take photos out of boredom, I am trying to capture the excitement and the frenzy of events that I am living through. This is one of the problems with photography, it can distract from the immediate enjoyment of an event. I sometimes prioritize the memory of that event rather than living in the moment. The payoff is that these images have the potential to capture something greater than simply “enjoying the moment.”

CE: Susan Sontag’s reflections on photography unveil a stark critique of touristic imagery suggesting ways the practice can be deeply problematic. She sees the act of photographing as one of appropriation, a way to impose one’s own presence upon the world and thus claiming a form of power and knowledge. Every click of the shutter asserts dominion over the captured space, a way for tourists to tame and possess the unfamiliar. Can you talk about the title of your book Conqueror in relation to Sontag’s critique?

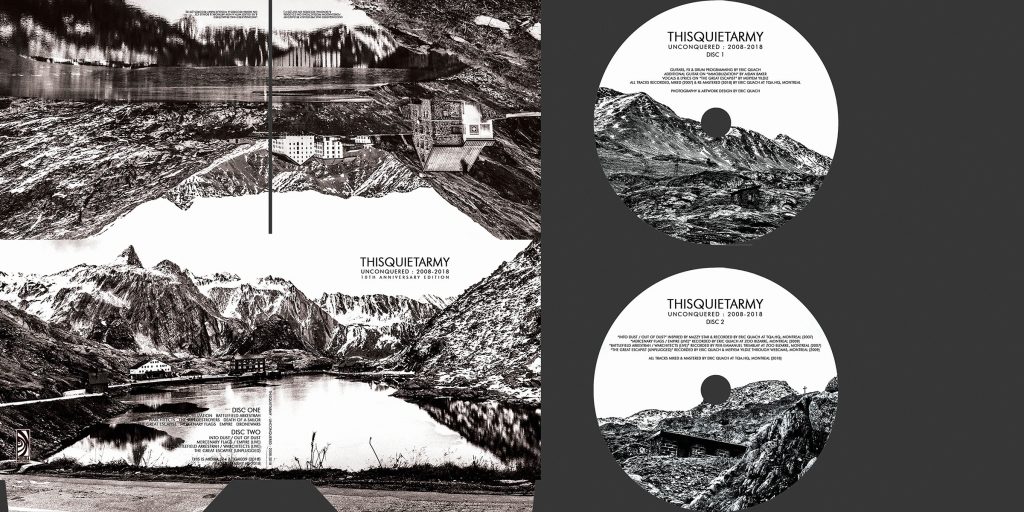

EQ: The title Conqueror is a reference to my first solo album Unconquered. At the time, I was working in a new medium, one that I had yet to master. It was also a reference to my artist name thisquietarmy which I envision as a journey, as the start of a long series of battles. Every completed work felt like a victory. Conqueror takes that same concept and applies it to touring where every performance, every concert, every city or country played and thus every moment was a conquest. In the context of photography, every snapshot is a trophy, a souvenir, a memento of that achievement. Am I imposing, appropriating, conquering the subjects of my photographs? Yes, of course, but not in the way Sontag claims. These are personal, not political, victories.

Quiet Addendums

CE: Coming from a background in mechanical engineering and working within the industry for several years, what made you turn your back on the corporate machine in order to pursue the raw act of making?

EQ: Like many from the Vietnamese diaspora living in Montréal who were raised by first-generation immigrants, I was encouraged to follow a professional path to “achieve success” in a respectable field. In spite of my artistic tendencies, my parents, both engineers and war refugees, pressured me to study engineering. I pursued a degree at Polytechnique and worked in various industries and sectors such as energy, metallurgy, hydroelectricity, petrochemicals, and essential infrastructures.

I escaped to music and art in order to cope with the daily grind, the forty-hour work week, the work performance evaluations, the coworkers void of interest, the lack of work-life balance.

CE: Can you talk about your use of video for live shows and shed some light on your audio/video collaborations?

EQ: thisquietarmy performances have always involved some visuals when possible, a way to further engage the listener. Like my music, I often try to layer different sources of visuals together and blend them to create something new.

A/V collaborations allow me to focus solely on the music performance rather than splitting my senses between audio and visual. I also perform differently in both configurations. Over the years, I performed with Guillaume Vallée, Timo Dufner, and Alexandre Larose. I was teamed up with Philippe Léonard by the curator of a series of A/V events called “Soirées d’expérimentation audiovisuelles”, which paired musicians with visual artists to produce a live performance. In the process of preparing for this event, Philippe and I ended up booking the “Alchemic Rites” tour in Europe.

With Philippe, it is quite intuitive and improvised—his vigorous performances feel more like a dynamic collaboration than my own static visuals which sometimes feel as though I’m creating a live soundtrack for a film.

CE: Is it true that Philippe started experimenting with video after lugging two 16mm projectors around Europe with you?

EQ: In contrast with his luxurious tour bus experiences with Godspeed, it was a gruelling tour for Philippe. In order to maintain the integrity of our “live expanded cinema” performances, he brought two 16mm projectors which he carried in a heavy road case without wheels. The projectors also required a 15 kg voltage converter. We travelled for two weeks, just the two of us, solely by public transport. At our next event at la lumière collective following that tour, he surprised everyone by using only a laptop and a midi controller. We worked on a new performance with this permutation throughout the pandemic and finally presented it as “MSC-ZOE – 01.01.19” at MUTEK in Montréal.

CE: What was life on tour like?

EQ: What most bands get to see on the road is their bus or van, gas stations, hotels, and venues. They barely have time for anything else—they are continuously in work mode: the distance drives, load-ins, set-ups, soundchecks, interviews, photo shoots, performances, tear down. And all of this on just a few hours of sleep.

Grant Gee’s extremely unromantic/unglamorous tour documentary about Radiohead, Meeting People Is Easy (1998), had a huge impact on me as it captured the band members’ stress, struggle, and fatigue during their tour. I have tried to avoid the pitfall of touring by actually making time to experience different cultures and to actually get to know people. This is hard to do if you tour with others.

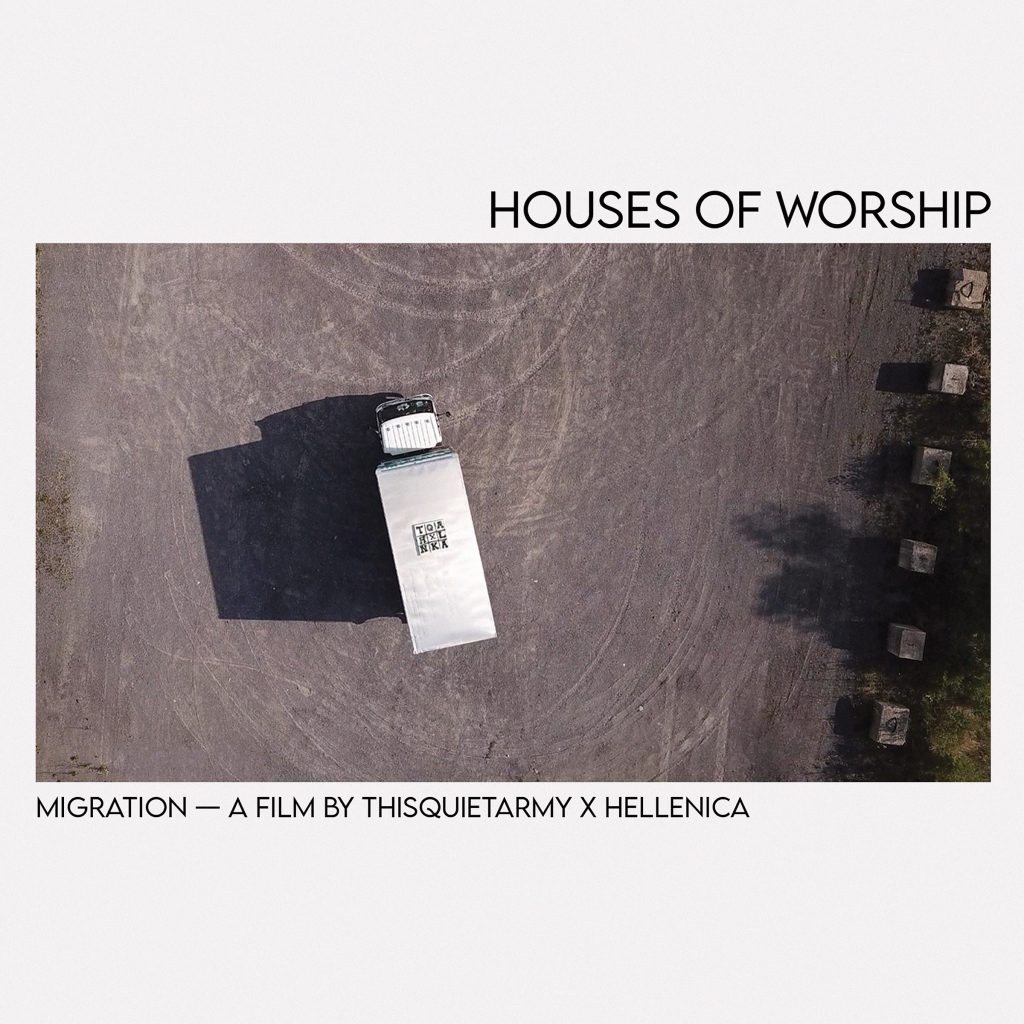

CE: In recent years, you have dabbled in a more conceptual approach to music making, in particular, in your collaborations with Jim Demos [Hellenica]. In 2021, you performed several live sets on the streets of from a cube truck. The project was documented in a short experimental film “TQAXHLNKA: MIGRATION.” Not only are cube trucks somewhat iconic in Montréal given that Canada Day is officially called Moving Day in Québec, it is also a reflection on the lack of venues, studios, and artistic spaces due to both the pandemic and gentrification. Can you discuss collaborating with Demos?

EQ: Jim and I started making music together at his old jam space—now vacant of artists. Under the collaborative name “Thisquietarmy x Hellenica,” we recorded an album called “Houses of Worship” (which has since become our band name). We wanted to find a way to perform it live in public, but pandemic restrictions were still in place and we weren’t allowed to gather in closed spaces. Since Jim was a mover for a living, we had access to a cube truck. It seemed like the perfect platform to bring our music to the public. A way to disrupt without “breaking” pandemic-era lockdown rules and without asking the city for permission. It was also a way to take back public spaces and to give something back to our community, especially during a period that was socially and emotionally difficult. Like Jim’s studio, many lofts, galleries, and venues were lost due to the pandemic, which has accelerated the gentrification process in Montréal. The artistic landscape of the city has definitely changed.

CE: In 2023, you also collaborated with Demos on an installation Les cabines télésymphoniques for Festival International de Musique Actuelle Victoriaville. Two interactive telephone booths invited visitors to collaborate on new real-time compositions using the touchtone dial pads. While the telephone was often seen as a way to connect people over distances, it was also a way to disrupt, to prank, to wreck havoc at a distance. For instance, consider the rich history of telephone phreaking and telecommunications hacking. Were the “official” Bell telephone booths stolen from the streets of Montréal?

EQ: This was another pandemic idea, trying to find new ways to perform at a distance. In short, the phones were designed to emulate both our sounds, in a way that any kind interaction would be captured by a static feedback loop that would then replay the played sound as a “mise-en-abyme” continuous soundscape, which would generate a Houses of Worship concert, played by the public. We also hacked the handsets as an effected microphone and as an in-ear monitor to listen to everything that is going on in real time, and through the feedback loop.

Did we steal official Bell telephone booths? No. Did we try to? Yes.

Trying to obtain official telephone booths involved a lot of calls and bureaucracy and red tape that, in the end, went nowhere. We eventually found a telephone repairman in Alberta who had a backyard full of these phones, all working condition. To be fair, these phones are very hard to vandalize, and were designed to withstand a lot of abuse. It was all worth it, seeing hundreds of children and adults play with our installation every day.

CE: While being incredibly prolific, you also make the majority of your artistic output available for free online. Do you see this as part of a DIY methodology in the digital age or as an anti-capitalistic gesture? Or do you see the digital as the sanitized version of your release, where the ideal form is the physical record, perfectly imperfect, in-flux, revealing its own slow decay?

EQ: With digital recording, your art exists at the highest bitrate that your own technology can record at, and can be stored on an online server. Any physical reproduction becomes a lower fidelity, more beautified version of it—a packaged product made to be marketed and sold, consumed, and collected. They involve more financial risk, they create a larger carbon footprint, they’re expensive to ship—they are unnecessary. This seems contradictory as most of my income comes from the sales of these physical products. Did I leave my career only to fall into another paradox?

It is now possible to make art with very little means—and very little risk. I want people to have full access to my art, whether they are able to afford it or not. If they have the means and like the work, I believe they will support the artist so that they are able to make more. When all is said and done, I hope my work can help people get through their day, open up people to new avenues of exploration, inspire people to follow their own creative visions.