“Psychedelic Agit-Pop: The Animated Films of Tadanori Yokoo.” Pop Cinema edited by Glyn Davis & Tom Day (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2024): 94-114.

In the 1960s the social and political conditions of postwar Japan generated a frenzy of artistic innovation within a wide range of practices including theatre, cinema, literature, music, illustration, graphic design, dance, and performance art. As art historian Alexandra Munroe states, it was “undoubtedly the most creative outburst of anarchistic, subversive and riotous tendencies in the history of modern Japanese culture.”1 It was in this artistic climate that the renowned Japanese artist Tadanori Yokoo first began to experiment with graphic design. Through blending Pop art, psychedelia and traditional Japanese aesthetics, in particular, ukiyo-e (a genre of Japanese art which has been considered proto-Pop), Yokoo created works that are playful, humorous, personal, and idiosyncratic.2 In 1968, Yokoo’s friend, author Yukio Mishima, provocatively declared that Yokoo’s graphic works connected “a straight line through the sorrow of Japanese local customs (dozoku), and the idiotic and daylight nihilism of American Pop art.”3 It was this particular aesthetic cocktail that landed him the reductive and Western-centric nickname of the “Japanese Warhol.” At the time, Yokoo was at the centre of the Japanese counterculture, collaborating with pivotal figures in the scene including filmmaker Nagisa Ōshima, playwright-poet-filmmaker Shūji Terayama, playwright-director-actor Jūrō Kara, choreographer Hijikata Tatsumi, and musician Toshi Ichiyanagi. Although predominantly known as a graphic designer and painter, Yokoo also produced three short animations.

This chapter will situate Yokoo’s animated films in relation to his overall artistic practice, and the social and political context in which they were made. A brief analysis will be performed on all three of Yokoo’s animations: Anthology No. 1 (1964, アンソロジーNO. 1), KISS KISS KISS (1964) and Kachi kachi yama meoto no sujimichi (1965, 堅々獄夫婦庭訓).4 Expanding on this analysis, a close reading will be provided of Yokoo’s most complex animation, Kachi kachi yama, a work that alludes to the revolutionary potential of popular culture. While working on his animations, Yokoo abandoned commercial graphic design. At this time, he began to pursue his own idiosyncratic artistic expressions, blending psychedelia and Pop art aesthetics, producing artworks that advocate for political change through expanding consciousness and through everyday actions rather than explicit political action.

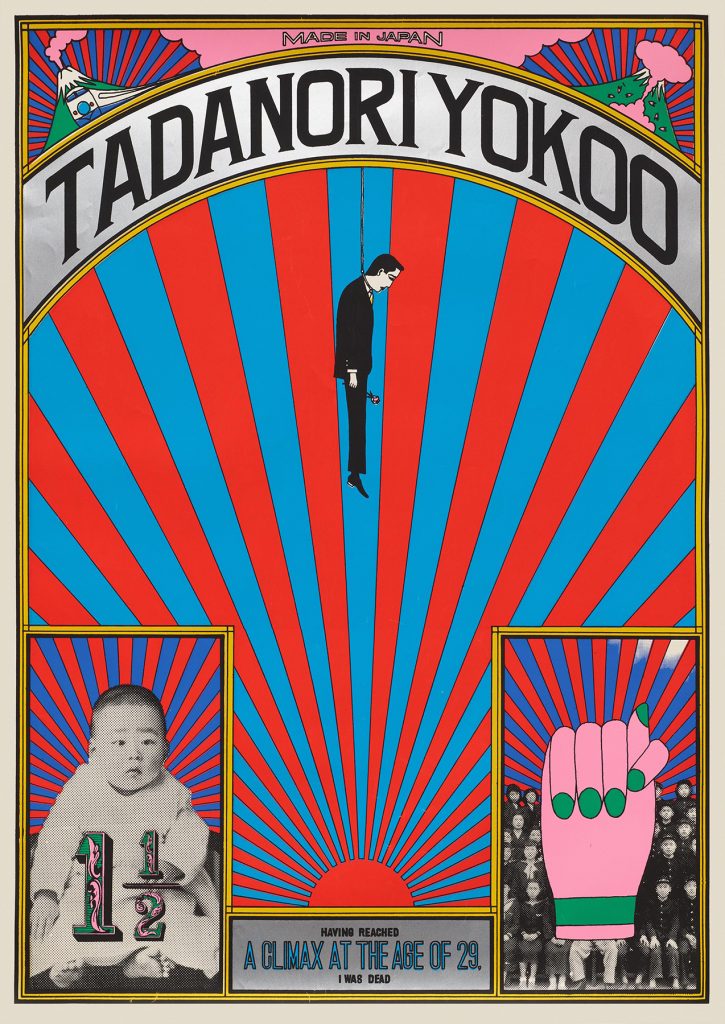

Age of 29, I Was Dead (1965), Tadanori Yokoo

Climax at the Age of Twenty-Nine

In 1965, Yokoo created a graphic poster titled Made in Japan, Tadanori Yokoo, Having Reached a Climax at the Age of 29, I Was Dead. The poster embraces a Pop style with its simplified flattened imagery, bright artificial colours and combination of text and image, while also incorporating elements which were distinctly Japanese, both modern and traditional. At the centre of the composition is a man hanging from a noose, holding a drooping flower in front of the Rising Sun, an image inspired by the Kyokujitus-ki military flag, a controversial symbol of Japan’s imperialism banned during the US occupation from 1945 to 1952. It also contains many of the aesthetic and visual motifs that Yokoo would continue to employ, including atomic explosions, an erupting Mount Fuji and the speeding Shinkansen bullet train. The poster was shown at Tokyo’s Matsuya department store in a group exhibition titled “Persona” and established Yokoo’s reputation as a graphic artist. The piece is intended to be allegorical; however, according to art critic Christopher Mount, “some believed at the time that [Yokoo] had really died.”5

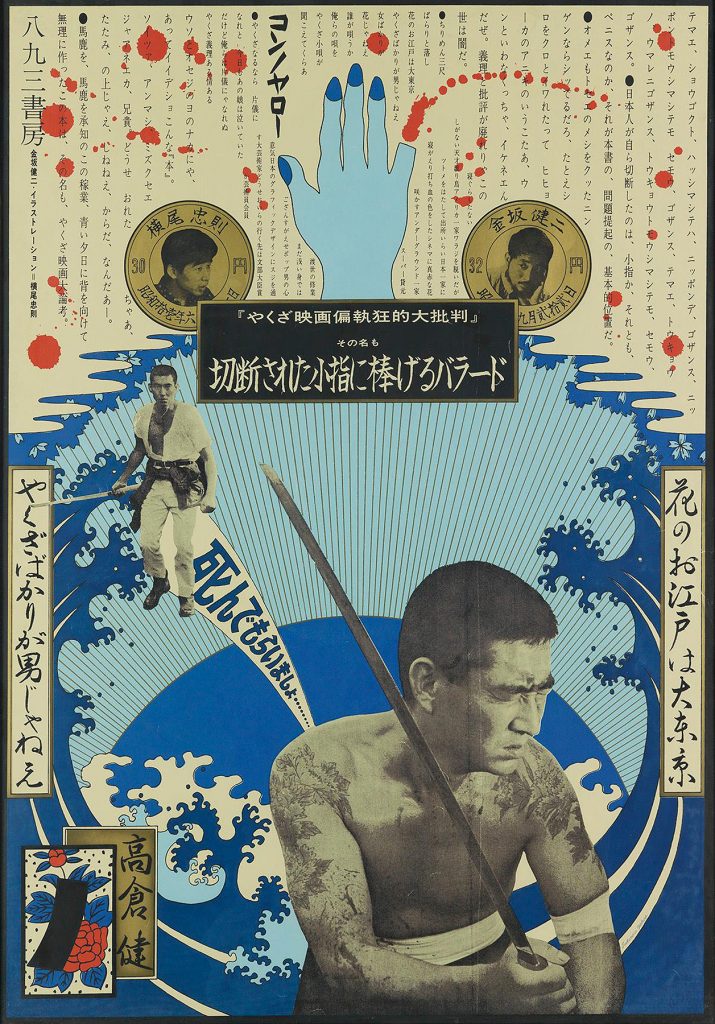

The graphic announcement of Yokoo’s symbolic death marked his departure from traditional commercial design to a more self-conscious and radical form of practice. As art historian Hiroko Ikegami has argued, at the time Yokoo had “uneasy feelings about being known as a mere ‘designer’ as opposed to an ‘artist,’ and was skeptical of the art-world term ‘Pop’.”6 These sentiments were expressed in a 1966 graphic poster titled Ballad for the Chopped-off Little Finger, an homage to the thespian achievements of Ken Takakura, an actor best known for playing ultra-hip tough guys with dignity and honour in gangster (yakuza) films. The text on the image, which lies somewhere between a loyalty oath of a yakuza member and the strict samurai code of the bushido (the way of the warrior), reads: “Although still inexperienced in the world, I, with the spirit of a false Pop man, pursue the proper road of graphic design in Japan.”7 Scholar Steven Ridgley argues that, by January 1969, Yokoo had completely overcome all of his reservations about being a commercial designer” and had begun to practice “without remorse.”8 By this time, Yokoo had developed an awareness of the potential dangers of commercialism and a consciousness regarding contemporary sociopolitical conditions. As Ridgely reasons, “what we find in Yokoo’s position on commodified art is a perfect example of counterculture’s adjustment from full-spectrum market boycott toward a more precise consideration of who is exchanging what with whom, where that exchange is occurring, and on whose terms.”9 As such, Yokoo continued to produce commercial design that was both idiosyncratic and personal. As art critic Yasushi Kurabayashi observes, “Yokoo’s posters are not designed around conventional poster-like ideas. Rather his posters have been executed from his own desire for creative expression, with little regard for cognitive clarity or message.”5

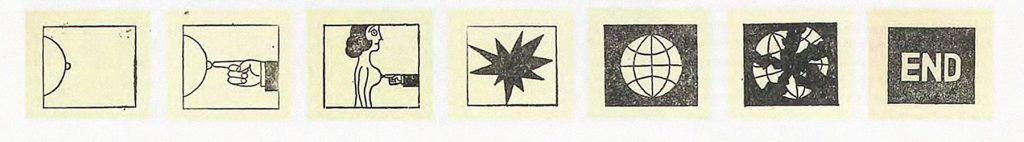

Yokoo’s animation Anthology No. 1 was made at the end of his four-year stint at the Nippon Design Centre (1960–64) and prior to Made in Japan. Like all of Yokoo’s animations, the work was produced through the Sōgetsu Art Centre, a Toyko-based experimental hub for postwar avant-garde art. At the time, experimental animation was relatively new to Japan, and Anthology No. 1 and KISS KISS KISS premiered at the inaugural Sōgetsu Animation Festival in September 1964. The source materials for Anthology No. 1 are Yokoo’s commercial graphic design work (publicity posters, magazine and book covers) produced between 1961 and 1964. The film is literally an anthology; however, the film is not simply a documentation of his commercial graphic designs given that none of the works are shown in their entirety. The animation consists of details from his graphic designs and, in a few cases, elements from these works are re-configured into new designs and given animated motion.10 As scholar Yuriko Furuhata suggests, Yokoo’s animation “foregrounds the static, graphic quality of unanimated images.”11 In the film, the camera minimally animates the source material producing a form of discontinuous animation that is not necessarily intended to produce the illusion of movement. As Furuhata notes, many Japanese graphic designers of the era were exploring ‘graphic animation’, a term coined by animation critic Takuya Mori to “describe the intermedial form of graphic design and animation.”12

It has been argued that Anthology No. 1 functions as an archive of Yokoo’s early graphic design while also revitalising the work through remediation. For example, Furuhata suggests that “animation allows Yokoo to both preserve otherwise ephemeral works of graphic design and to breathe new life into them, all the while highlighting his investment in repetition as a central component to his artistic process.”12 While Anthology No. 1 successfully reinvigorates his older work, it is, at best, a rather poor attempt at preserving his graphic design work. A film that fully documents his works in their entirety would have made for a better archive. Nevertheless, to expand on Furuhata’s line of reasoning, the film not only attempts to ‘breathe new life into’ his previous work, but also attempts to artistically reclaim his commercial work in a desire to move beyond it.

One of the last images in the film, the one immediately before the end title (with “終” [“End”] emerging from a mouth) is a detail from a 1964 graphic poster, The Performance of Gekidan Mingei: Under the Magnolia Tree.13 The image depicts a cross marking a grave beneath a tree, which is consistent with the play which Yokoo’s poster was advertising; however, given that this was the last image of the animation and that it is shown without any reference to the play, it can be seen as signifying the end of life. Although not as striking or as explicit as Made in Japan, this gesture can also be seen as further indicating Yokoo’s departure from traditional graphic design and subsequent rebirth as a graphic artist in pursuit of his own personal, psychedelic, Pop art aesthetic.14

Lichtenstein, Warhol and Yokoo Sitting in a Tree, K-I-S-S-I-N-G

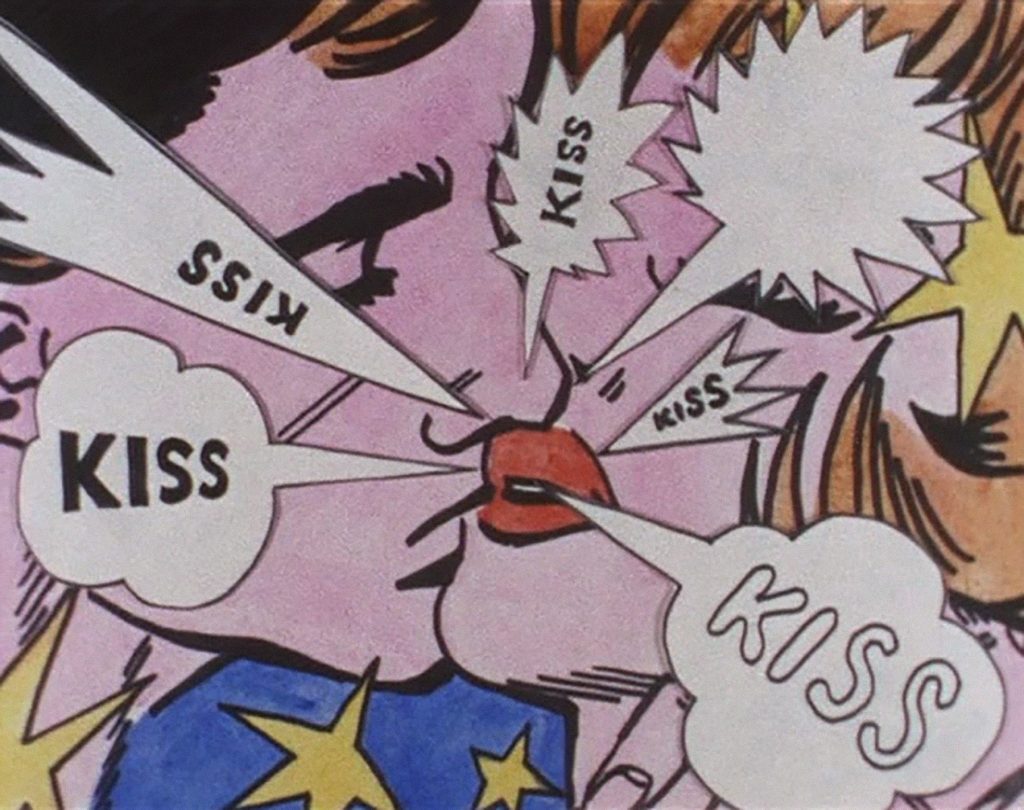

KISS KISS KISS is a 1964 animation that borrows the aesthetics of American romance comics and features hand-coloured illustrations of couples kissing. The soundtrack, composed by Akiyama Kuniharu (who also made the electronic soundtrack for Anthology No. 1), begins with crooner Dean Martin singing his 1953 pop hit “Kiss,” which abruptly changes after the title cards disappear, to electronic bloops that mimic the muah sounds of people kissing.15 In addition, the word “kiss” appears in speech bubbles around the figures embracing . The animation itself is minimal, with little movement, and makes use of lo-fi transitions – one repeated form of which is a ripping of paper, beginning as a small hole at the place of two lips kissing, swiftly becoming larger until the next kiss is revealed. The film ends with a title card (“The End”) and the sound of Martin repeating the phrase “kiss me, kiss me again,” as if the record were skipping, until it slowly fades out.

The images in KISS KISS KISS are reminiscent of Roy Lichtenstein’s Kiss series (1962–64), which was a source of inspiration for Yokoo.16 Following Lichtenstein, Yokoo sourced the material for his film from American romance comics produced after World War II. Both artists are playing with he tension between the artwork and the newsstand source from which they were appropriated. One difference between the two artists’ works is that Yokoo’s images lack Lichtenstein’s signature Ben-Day dots since he created new illustrations for his film; that is, he did not photograph them directly from comic books. Beyond removing the Ben-Day dots, Yokoo also includes an image of the moon which Ikegami suggests is taken from the Japanese card game hanafuda.6 In this way, Yokoo is subtly mixing Japanese and Western images, juxtaposing indigenous Japanese popular culture with Western popular culture, a gesture which can be interpreted as a response to the Westernisation of postwar Japan.

Both Yokoo and Lichtenstein extract the objects that they are appropriating from their original context, a strategy that both celebrates them and opens them to scrutiny. In addition, both artists employ a number of different techniques to manipulate, remediate and transform the objects that they appropriate from mass culture. Beyond an actual transformation, Lichtenstein argued that his work effected a slightly more abstract form of critical transformation: “the closer my work is to the original,” he stated, “the more threatening and critical the content. However, my work is entirely transformed in that my purpose and perception are entirely different. I think my paintings are critically transformed, but it would be difficult to prove it by any rational line of argument.”17 While the degree to which Lichtenstein simply copied his source materials has been the subject of much debate, it is certain that he transformed what some critics perceived as “low brow” material into “high art.”18 Yokoo describes his use of appropriated images in a slightly different way, arguing that “each of these mass-produced works that appear on screen [in KISS KISS KISS and Anthology No. 1] are ruins of the former works, robbed of their short life after being exhausted on the commercial front. [ … ] I am playing the role of a spiritual medium who conjures their spirits from the ghostly past and confers on them a new light of life.”19 In other words, Yokoo sees both KISS KISS KISS and Anthology No. 1 as providing a second life to mass-produced, popular images that had “exhausted” their intended commercial function.

By the mid-1960s, Lichtenstein’s aesthetic was already being appropriated by commercial advertising agencies. In June 1964, Brazil Coffee released a one-page advertisement in the New York Times Magazine in a style similar to Lichtenstein’s romance paintings, only one month after the magazine had published a substantial article on Pop art by John Canaday.20 As Thomas Crow has demonstrated, Pop art aesthetics were quickly re-absorbed into the commercial sphere, with commercial designers appropriating the self-conscious nature of the artworks. By 1965, Lichtenstein had stopped using comic book panels as source material, and by the end of the 1960s, Pop art was largely abandoned by the art world (although it was to re-appear in different forms).21 However, the influence of both Lichtenstein and Yokoo’s works have outlasted the ephemeral, mass-produced images from which they borrowed.

While KISS KISS KISS engages with a Pop aesthetic similar to that employed by Lichtenstein, the film also employs formalist strategies that date back to the Edison film depicting the first on-screen kiss. The May Irwin Kiss (1896), directed by William Heise, is a filmic adaptation of the final scene of the musical stage comedy The Widow Jones, a kiss between actors May Irwin and John C. Rice. Approximately fifteen seconds in length, the film was originally projected on loop using a Vitascope. In other words, the shot of Irwin and Rice kissing was repeated multiple times. The film was “the most popular Edison film of the year,” notes film historian Charles Musser.22 Many of the critics of the era saw the film as humorous. For instance, one described the “evident delight of the actor” and “the undisguised pleasure of the actress” as “‘too funny’ for anything.”23 Exactly what was the anything? Others were scandalised:

In a recent play called The Widow Jones you may remember a famous kiss which Miss May Irwin bestowed on a certain John C. Rice, and vice versa. Neither participant is physically attractive, and the spectacle of their prolonged pasturing on each other’s lips was hard to bear. When only life-sized it was pronouncedly beastly. But that was nothing to the pleasant sight. Magnified to Gargantuan proportions and repeated three times over it is absolutely disgusting. All delicacy or remnant of charm seems gone from Miss Irwin, and the performance comes very near indecent in its emphasized vulgarity.24

Film theorist Linda Williams describes this vulgarity as cinema’s “first sex act.”25

In the mid-1960s, the decontextualised kiss would return to the screen in Andy Warhol’s serial Kiss (1963–64). Warhol’s Kiss consists of different couples kissing and was originally shown as a “serial,” with “a new segment shown every week at the [Film-Makers’] Cinematheque, like Merrie Melodies.”26 The final film is made from twelve black-and-white, 100-foot 16mm reels, spliced together, complete with burns and perforated end tags. There are no titles or credits; like most of Warhol’s silent films, it was shot at 24 frames per second but projected at 16 fps, producing a dream-like effect, stripping away the sexual impact to reveal the banality of the action and providing space for quiet contemplation of the on-screen performances.27

Warhol’s Kiss and Yokoo’s KISS KISS KISS share particular formal affinities with Edison’s The May Irwin Kiss, including fragmentation, repetition and magnification. For Yokoo, each kiss is just one panel from a comic book, a single drawing representing a frozen moment. In the case of The May Irwin Kiss, the kiss is removed from its original context within a play. Warhol rejected any semblance of traditional narrative, allowing new sets of questions to arise. As filmmaker and theorist J. J. Murphy observes,

Hollywood kisses seem to erase questions, while these messier ones [in Kiss] tend to raise them. For instance, we become quite aware of the element of performance in each kiss. Some actors seem to be actively engaged in the act of kissing, while others clearly are not. The kisses reveal the personalities of the performers, or at least something about the situation. Are these people being asked to kiss friends, foes, lovers, or strangers?28

All three films consciously remove the kiss from any narrative constraints, emancipating it from previously established cultural conventions.

The looping of The May Irwin Kiss was a by-product of the technology.29 In contrast, the repetition with variation found in both Warhol and Yokoo’s work was intentional. The repetition of The May Irwin Kiss potentially contributed to the laughs, whereas for Yokoo it enhances the banality of the act. When asked about the use of erotic or sexual imagery in his work, Yokoo stated: “I think that I wanted to show the banality of sex in the best possible way. For the generations that came before in Japan, sex was not something that needed to be made pornographic, it was natural. If everyone’s working out in the field and mom and pop want to have a break and take five or ten to do a sweet one – that was normal.”30 The repetition in Warhol’s films contributes to their monotony; however, they also force the viewer to consider slight variation. As Warhol famously declared, “[e]verything repeats itself. It’s amazing that everyone thinks that everything is new, but it’s all a repeat.”31

Finally, all three films use a form of magnification. In The May Irwin Kiss, the couple is framed in chest-up shot, a marked close-up compared to the theatre production. Warhol uses a two-person close-up for every couple, except for the third reel where there is a slight narrative set-up. In the third reel, the camera zooms back to reveal experimental filmmakers John Palmer and Andrew Meyer topless and kissing. This may have been shocking to some since, in close-up, some viewers might have assumed that the couple kissing was heterosexual, given Palmer’s androgynous features. In Yokoo’s work, the illustrated kissing couples are framed both chest-up and as two-person close-ups. Yokoo also uses another technique to isolate the kiss, a simple matting device: a black frame which blocks out much of the image and draws focus to the kissing lips.

KISS KISS KISS blends two aspects of Yokoo’s political philosophy – namely, the revolutionary potential of everyday gestures and sexual liberation. In an interview with curator Takayo Iida, Yokoo explains that “the real revolution was perhaps in those simple everyday gestures. I think the most important inner activity is not to deliver political messages, but rather to transform consciousness and our daily activities.”32 To Yokoo, sexual liberation is directly linked to political revolution. As Ridgely elegantly states, Yokoo “was on the psychosexual side of 60s politics, interested in a transformative heightening of consciousness that could direct the libidinal trauma of war and the repressed Thanatos of the Cold War into a broad cultural response rather than a limited political action.”33 Viewing KISS KISS KISS through this lens, the kiss serves as a simple everyday gesture, an act of intimacy shared between two people that contains the potential to heighten consciousness and transform the dominant culture.

The psychosexual aspect of Yokoo’s political philosophy becomes particularly apparent in Nagisa Ōshima’s Shinjuku Dorobō Nikki (Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, 1969), a film for which Yokoo not only designed the poster, but that also features him as one of the main actors.34 The film explicitly links sexual liberation with political revolution. As Ōshima explained in an interview with Joan Mellen, the sexual inadequacies of the two lead characters Birdey Hilltop (Yokoo) and Umeko (Rie Yokoyama) are political inadequacies; sex and politics cannot be separated.35 Given that Birdy Hilltop was based on Yokoo’s real persona, the film further demonstrates Yokoo’s belief that there is a connection between revolution and consciousness expansion – in this case, as a form of sexual liberation.36 A similar line of reasoning can be identified in a flip book animation that Yokoo produced for Shūji Terayama’s experimental novel Sho o Suteyo Machi e Deyō (Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets , 1967). The kineograph begins with a countdown from sixty-nine to zero, prompting the pushing of a button which is revealed to be a woman’s breast. This sets off three explosions, blowing the world into tiny pieces. END. Reading the work literally, a sexual act sets off a transformation of the world. This anarchic animation uses humour to demonstrate the power of the sexual impulse.

While KISS KISS KISS is not as explicit as these two works, it puts into action Yokoo’s political philosophy. In the film, Yokoo extracts the kiss from its original context within a romantic narrative, sexualising the act; it becomes, literally, a gesture of sexual liberation. Its revolutionary potential is not linked to an overtly political act, but rather to an everyday gesture, a passionate demonstration of affection. The animation eschews an overt political message, but instead magnifies an act of intimacy.

Illustrated Stories of Cannibalism for Children

Yokoo’s animation Kachi Kachi Yama Meoto no Sujimichi is arguably the most complex of his animated works. Like KISS KISS KISS and Anthology No. 1, the film is an example of remediation; however, it is also an adaptation or, more precisely, a re-adaptation of an adaptation. The animation is based on a graphic story by Yokoo and poet Mutsuo Takahashi, which originally appeared in a 1964 anthology titled Nihon Minwa Gurafikku (Japanese Folktale Graphics, 日本民話グラフィック), which paired graphic artists with writers to re-imagine Japanese folktales.37 Yokoo and Takahashi collaborated on an adaptation of Kachi Kachi Yama (Crackling Mountain or Click-Click Mountain, かちかち山), one of the best-known Japanese folktales.38 Both the graphic story and the animation make use of a Pop graphic aesthetic and blend Japanese and Western iconography.39

Kachi Kachi Yama is a violent tale of torture and revenge that involves an old farmer and his wife, a mischievous shape-shifting tanuki (a Japanese raccoon dog that is often mistakenly translated as a badger or raccoon) and a rabbit. A succinct summary of the story appears in the Nippon Bungaku Daijiten (Standard Dictionary of Japanese Literature, 日本古典文学大辞典):

An old man traps a bad badger [the raccoon dog or tanuki] in the mountain, brings it home and hangs it from the ceiling, tying its legs together. After he has gone to work again, the captive badger persuades the wife to untie the rope. When freed, the badger kills her and makes soup of her. He disguises himself as the wife, and when the old man comes home, serves him the soup calling it badger soup. The badger taunts the old man that he has eaten his own wife, then flees.

A rabbit comes along while the old man is crying and promises to seek revenge for him. The rabbit by deception makes the badger carry firewood on his back, and from behind strikes a flint, ‘click-click’, to set fire to the firewood. The badger questions the sound, and the rabbit says that there is such a noise here because the place is the Click-Click Mountain. A similar explanation is given to the sound of burning wood on his back, before he realizes that he is afire.

Red-pepper plaster is applied as an ointment to the burns by the rabbit. When the burns have finally healed, the rabbit invites the badger for boating. Riding a wooden boat himself, the rabbit provides the badger with a boat of mud, which dissolves in the water and drowns the badger.40

Granted, this is only one version of the tale, and many variations exist; however, this version contains all of the core elements of the story and pro-vides an explanation of the title.

Notably, the folktale is educationally ambiguous and does not contain an obvious moral, but instead uses violence and torture for entertainment value. Scholar Lucrezia Morellato observes that “Kachi Kachi Yama, on the surface, presents a violation-punishment structure featuring a violent retaliation to justify a vendetta, which seems the ideological end of the story.” Although the violence in the story seems directed towards a moralistic end, she continues, the “violence stops being an accessory to the narration and becomes its protagonist in an excessive, festive way for a gruesomely comic effect.”41 While many Japanese folktales make use of violent retaliation, they usually incorporate an educational component. As Morellato suggests, “the bulk of the most popular Japanese folktales conforms to this description by overtly celebrating values such as obedience, perseverance and loyalty with no shortage of violent retaliation, punishment and reward plots and prohibition-violation-punishment schemes.”42

To read Yokoo’s adaptations of Kachi Kachi Yama requires an intertextual approach that references the original folktale and several pop culture sources. In the graphic story and animation, Alain Delon plays the tanuki and is lovers with Brigitte Bardot, both sex symbols of 1960s French cinema. Delon attained international success for his role in René Clément’s Plein soleil (Purple Noon, 1960), a film in which Delon plays Tom Ripley, a character who assumes another person’s identity, similar to the shape-shifting abilities of the tanuki in the folktale. At the time, it was also commonly assumed that Alain Delon and Brigitte Bardot were real-life lovers after the two had met and become close friends on the set of Michel Boisrond’s anthology film Les Amours célèbres (Famous Love Affairs, 1961). To further confirm that Delon is the tanuki, in the graphic story he is shown with his back on fire after returning home to Bardot, an image that is missing from the animation.

The old couple in the graphic story and animation is played by Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. In 1961, during the production of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra (1963), Burton and Taylor had begun a scandalous affair, both being married to other people at the time. The affair was well publicised and transformed from rumour into fact when a paparazzi shot of the couple embracing emerged. It is the Beatles and Bardot that perform the role of the rabbit in Yokoo’s adaptations. They team up with the grief-stricken Burton in order to exact revenge upon Delon for the murder of Taylor. In the animation, Marilyn Monroe is also listed in the credits along with these other previously mentioned pop culture icons; however, she only appears for a few seconds on a billboard advertising Coca-Cola and does not appear in the graphic story at all. As such, her “cameo” is an example of “false advertising.”

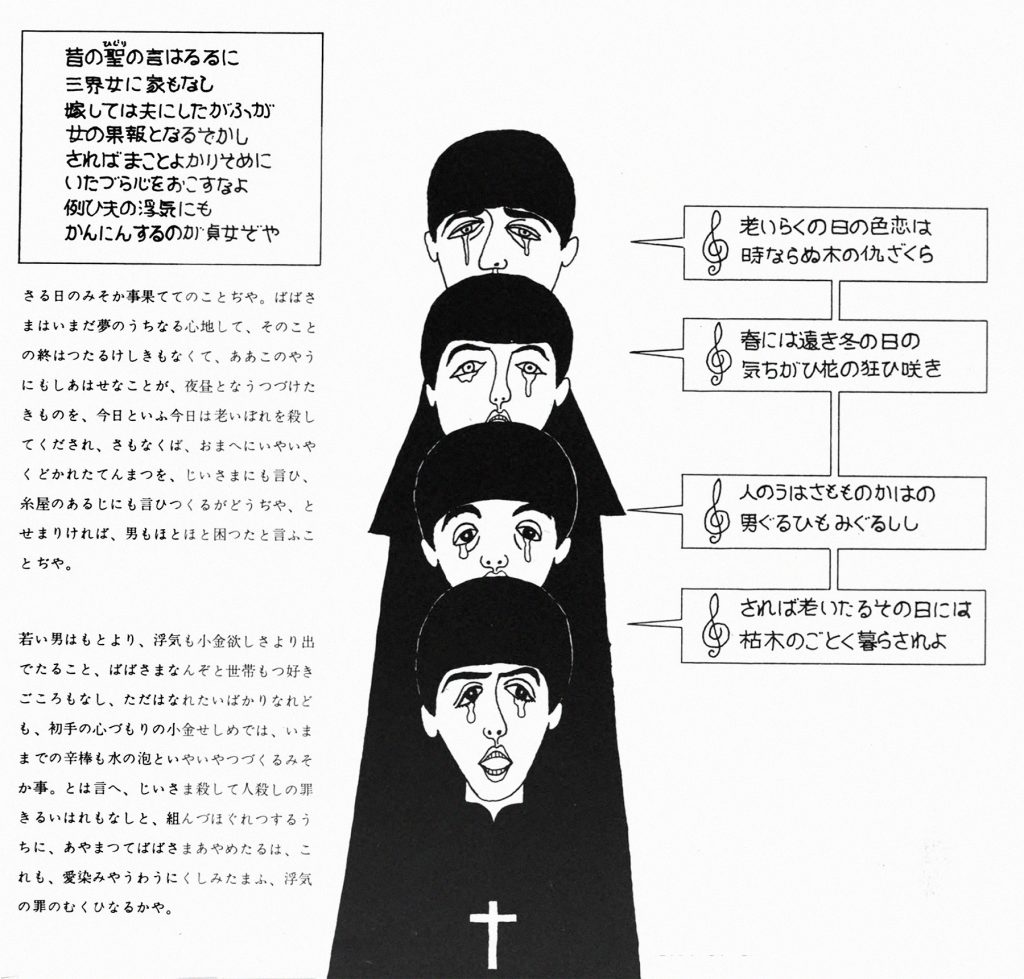

The folktale, the graphic story and the animation follow similar structures but also have a few key differences. To begin with, all are stories of revenge. Following the folktale, Delon murders Taylor in an attempt to steal her money, which is consistent with some versions of the folktale where the tanuki is caught stealing from the farmer. In the animated version, after Taylor is murdered, Burton needs somebody and screams “Help!” Of course, not just anybody shows up – it is the Beatles to the rescue. In both the animated version and the graphic story, the Beatles, with tears in their eyes and dressed as priests, sing a poem at Taylor’s funeral. In the animation, after the funeral and a brief commercial break advertising beer, we witness Burton sucking on Taylor’s toes: the cannibalism of the folktale is replaced by podophilia.

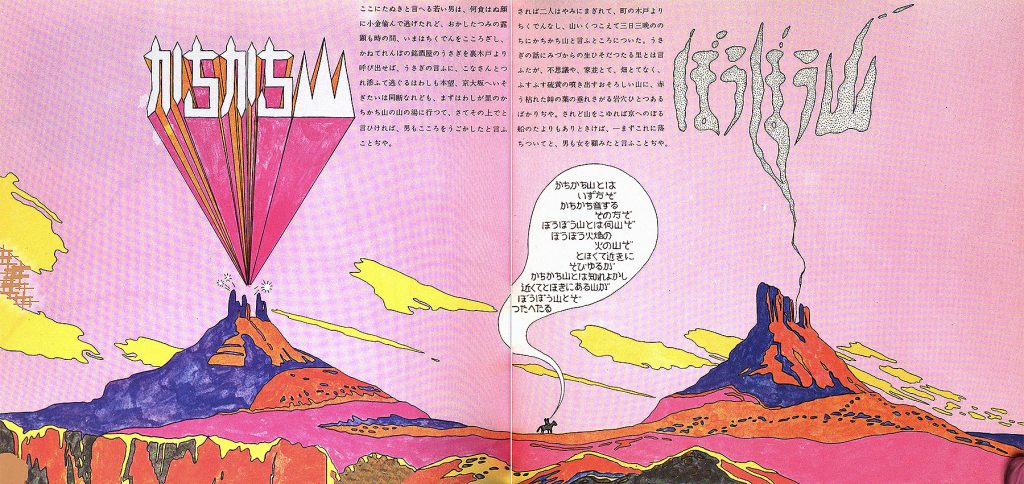

In a slightly perplexing scene, Delon, shown with the body of a skeleton, appears to Bardot. In the text of the graphic story, it is hinted that Bardot will help Burton avenge the death of Taylor, re-affirming that she, along with the Beatles, performs the role of the rabbit. As in the folktale, she will betray Delon, participating in Burton’s revenge. In the animated version, Burton and the Beatles, each in their own fighter jet flying in military formation, engage in a dogfight with Delon and Bardot’s plane, which is shot down with the couple narrowly escaping in parachutes. Later, the Beatles and Burton, now in a submarine, track down Delon and Bardot who are shown necking on an inflatable pool mattress in the middle of the ocean. The couple are blown up by three torpedoes, but again somehow manage to escape. In both the graphic story and the animation, Delon and Bardot escape from Burton and the Beatles by riding on a Shinkansen bullet train ascending Mount Fuji. The animation ends with Delon crying, in distress, and unable to embrace Bardot, with the sound of a woman laughing as a funeral note, with “家” (“Home”) written on it, blows in front of the Rising Sun. From the graphic story, we can assume it is Bardot who has the last laugh as money rains on her from Mount Fuji.43

In his autobiography, Yokoo claims that in his adaptation of Kachi Kachi Yama he was imitating the work of Ingmar Bergman and John Ford.44 Bergman’s influence can be seen in the dialogue, which is filled with bleak,poetic expressions of existential angst, philosophical profundities and fearsome visions of spiritual unrest, with Buddhism replacing Christianity. In addition, the graphic story and animation both begin with Bergman-esque symbolism – namely, Taylor holding an hourglass and Burton holding a scythe. Ford’s influence can be seen where Delon and Bardot are shown riding on horseback between two mesas (which have the text “かちかち山” [“Kachi Kachi Mountain”] and “ぼうぼう山” [“Bōbō Mountain”] rising out of them).45 In the animation, they are being chased by a posse consisting of Burton and the Beatles riding horses; everyone is wearing a cowboy hat.

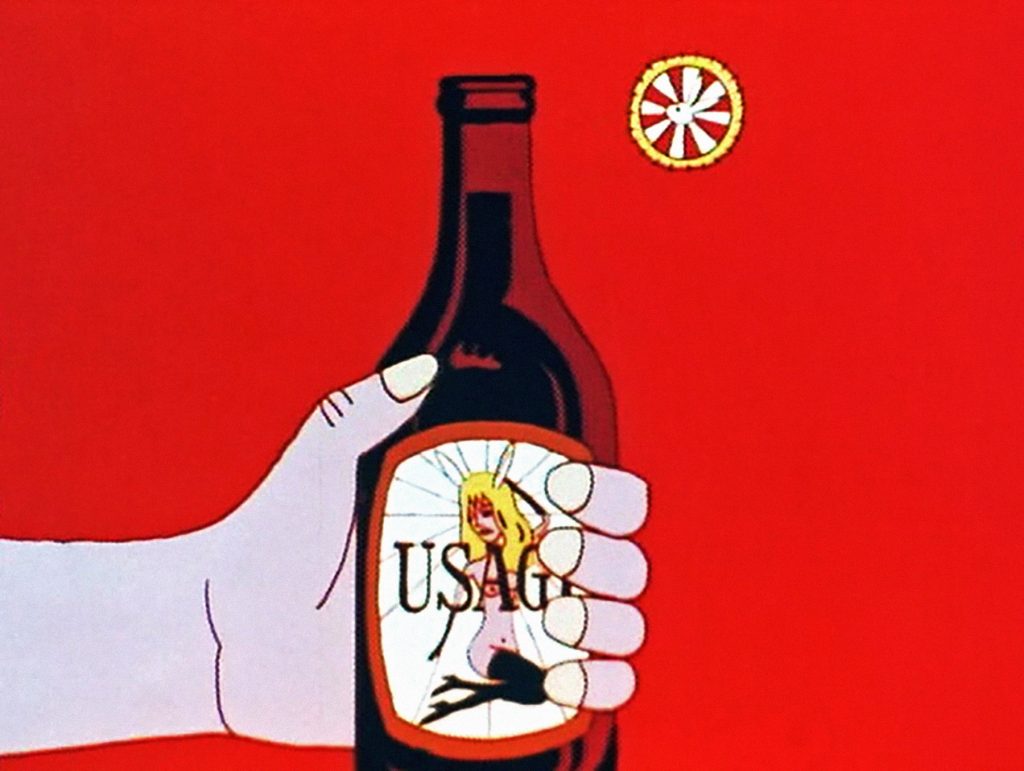

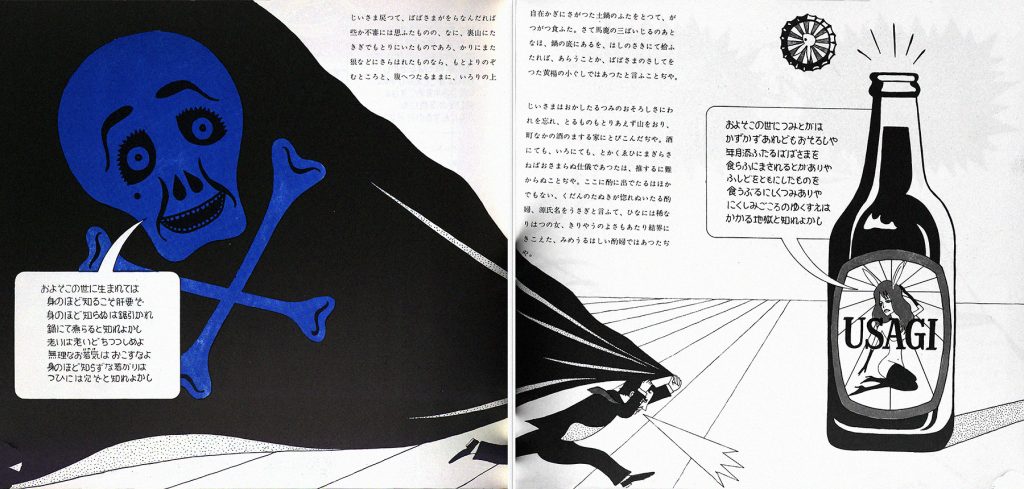

Both adaptations also contain a playful beer advertisement. The beer’s label reads ‘USAGI’ (‘Rabbit’) and depicts Bardot wearing only bunny ears and stockings. The bottle cap blends the Asahi trademark with the Playboy motif: a Rising Sun with a bunny head in the middle. In the graphic story the bunny declares:

Many sins in this world

are horrifying

What can be more horrible than

to eat an aging woman?

It is sinful to devour the one you shared a bed with

Know that a heart filled with hate

ends in hell like so46

In other words, the bunny explicitly makes a connection between the graphic story and the folktale and expresses Burton’s emotional state. In his autobiography, Yokoo explains that while working at Nippon Design Centre he saw Asahi’s “Nami ni asahi” (“Rising Sun and Waves”) trademark almost every day and that this was the inspiration for the Rising Sun in his work.47 It was also in 1964 that the Asahi Steiny mini bottle with the Rising Sun on its bottle cap was launched. Before the advertisement appears in the animation, a Buddhist sutra appears on the screen: “色即是空 空是即色” (“Form is empty, emptiness is form”).48 Zen in an era of consumer capitalism.

The graphic story, in many ways, can be seen as the birth of some of Yokoo’s visual motifs. In an interview, Yokoo stated that “it wasn’t until I was 28 or 29 [1964–65], after I became freelance, that I really developed my own voice,”49 and Kachi Kachi Yama visually marked a transition point in Yokoo’s work. Both of Yokoo’s adaptations contain the Rising Sun, Mount Fuji and a speeding Shinkasen train. Christopher Mount explains the significance of these images while discussing Made in Japan:

The train represented postwar Japan’s rapid and ultimately problematic development, which some felt had destroyed the country’s nobler traditional culture. Mount Fuji stood for that old world, and the rising sun symbolized the militaristic folly that led to Japan’s modern condition.5

The complexity of Yokoo’s work stems from the way in which it juxtaposes traditional and contemporary Japanese culture, as well as the way in which it blends Western and Japanese iconography. Yokoo’s use of nationalistic imagery is just as complicated. He explains:

I was specifically bringing in fascist or wartime imagery wrapped in the ambivalence and criticism and support of what it meant to me in my lifetime. [Yukio] Mishima, on the other hand, specifically would not allow those symbols in his work. He liked my work and appreciated that I could bring in ambivalence [ … ] He told me, ‘I criticize these things by not including them, but you criticize them by ambivalently including them’.30

Yokoo and Mishima were both responding to the anxieties experienced under the conditions of post-war Japan. Despite explicitly engaging with these symbols, Yokoo is less politically extreme than Mishima. Yokoo claims to treat this imagery with ambivalence in order to undercut its power; however, it is precisely due to this ambivalence that these images can also be read as a form of nationalistic pride, adding an additional layer of complexity to his work.

The ability to criticize culture ambivalently is precisely one of the strategies employed by Pop artists. However, this has also been one of the critiques leveraged against Pop art – namely, that this ambivalence leads to an ambiguity as to whether the work is complicit with or criticizing consumer culture. The ambivalent juxtaposition of American and Japanese iconography was also a strategy employed by other Tokyo Pop artists of the era, seen for instance in the work of Tiger (Kōichi) Tateishi, Keiichi Tanaami and Hiroshi Nakamura. The effect was two-fold: it was both a way of countering post-war American cultural imperialism through asserting Japanese culture and a way of demonstrating the impact that American culture had on the Japanese cultural landscape. As Ikegami has argued, “the products of Tokyo Pop can be seen, collectively, as a commentary not only on the colonizing effect of U.S. art and culture, but also on the ‘internal America’ embraced by the Japanese.”50 In 1969, Yokoo literally expressed this sentiment in a cover of Shūkan Anpo (Anpo Weekly), which featured a Pop-style illustration of Prime Minister Eisaku Satō, with his name printed over the image with the letters “U,” “S,” and “A” highlighted in red.

The soundtrack for Kachi Kachi Yama was composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi and comprises sound effects, musique concrète, classical music, traditional Japanese folk music and Buddhist chanting.51 Like the film itself, the sound design is idiosyncratic while still directly responding to the action on screen. For example, there is the sound of a crowd cheering when Delon steals the money from Taylor, and the film ends with a woman laughing feverishly. The Buddhist chanting was done by Takahashi and is repeated throughout the animation. The lyrics come directly from the opening of the graphic story, where Elizabeth Taylor, holding an hourglass, states:

This is not of this world

An old story from the past

Delusional but horrifying, the story of infinite hell

may frighten the young mind

but best to tell it with good intentions

As the old saying goes

spare the rod and spoil the child52

This self-reflexive statement seemingly addresses the horrific nature of the violence and torture in the original folktale while also suggesting that the tale can lead to personal development. While the graphic story alludes throughout to the teachings of Buddha, the animation is more in line with the original folktale in its use of violence for entertainment value.

Radical Approaches to Conflict Resolution

Kachi Kachi Yama was made before the Beatles’ animated television show (1965–67), before the Beatles would record “Yellow Submarine” at Abbey Road Studios, and three years before George Dunning would direct the animated film Yellow Submarine (1968). Stylistically, Yellow Submarine and Kachi Kachi Yama share similarities; in particular, both make use of limited animation, explore a style of psychedelic Pop art, and involve the Beatles manning a submarine. The Beatles are the “heroes” in Kachi Kachi Yama, but a type of hero very different from the one portrayed in Yellow Submarine, where they defeat the Blue Meanies by performing some “transformation magic” and by singing “All You Need is Love.” In Kachi Kachi Yama, the Beatles are heroes for hire who fire nuclear missiles from a submarine, a representation very different from the likeable, silly lads of A Hard Day’s Night (Richard Lester, 1964) or the peace-loving hippies of Yellow Submarine.

Kachi Kachi Yama asserts the revolutionary potential of popular culture through the use of the Beatles by representing them as heroes willing to hunt down villains who commit murder for personal profit. In a 1969 essay, Yokoo argued “that if revolution were going to come in the 60s, it would be via a pop group like the Beatles.”53 The radical potential of the Beatles was unleashed with John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s peace campaign (1969–70). This consisted of two bed-ins for peace, one in Amsterdam and one in Montréal, and an ad campaign that consisted of billboards reading “WAR IS OVER! If You Want It – Happy Christmas from John and Yoko,” which was intended to appear in Amsterdam, Athens, London, Los Angeles, Montréal, New York, Paris, Rome, Toronto, West Berlin and Tokyo. However, the “WAR IS OVER!” billboard that was slated for Tokyo did not make it; rather, Yokoo was hired to make a variation of the poster in order to advertise a “Christmas Party for Love and Peace” in the city.54

The peace campaign employed a commercial marketing strategy, with Lennon leveraging his celebrity status as a member of the Beatles to claim the attention of the press. As Ono explained in an interview with Penthouse magazine, “many other people who are rich are using their money for something they want. They promote soap, use advertising propaganda, what have you. [ … ] We’re using our money to advertise our ideas so that peace has equal power with the meanies who spend their money to promote war.”55 Lennon and Ono were using the commercial marketing system to promote counter-cultural ideology. As Ono explained to a reporter, “instead of becoming violent about it and saying ‘Stop the War’ or something, with violence, it’s better to say: it’s spring, stay in bed.”56 Similar to Yokoo, Ono argued not for delivering political messages through abrasive tactics, but in favour of a transformation of consciousness, revolution through the everyday gesture. Of course, many in the press expected scandalous photo ops and salacious copy, assuming that the couple would be doing more than just lying in bed, given that the first bed-in was on their honeymoon. However, the celebrity couple was serious about talking peace. Moreover, there was a gesture of inaction, as opposed to action, designed to lead to peace. As Lennon infamously declared, if everyone stayed in bed for a week, all wars would end.

Although the cartoon violence in Yokoo’s Kachi Kachi Yama may go against the non-violent stance of the peace campaign, the film portrayed the Beatles as more than just pop stars. Even though the revolution did not materialize, the Beatles and Yokoo left an undeniable impact. Since reaching his climax at the age of twenty-nine, Yokoo has been pursuing his own personal visions inspired by psychedelic and Pop art. He designed records such as Santana’s Amigos (1976) and Haruomi Hosono’s Cochin Moon (1978), books such as Eikoh Hosoe’s Barakei (Ordeal of Roses, 1971) and David LaChapelle’s LaChapelle Land (1996), as well as thousands of posters. In the early 1980s, Yokoo moved further away from commercial graphic design and began to pursue painting.57 By examining his early animations, it is possible to trace the origins of the visual motifs and political beliefs that ultimately made him one of Japan’s most renowned and influential artists.

- Donald Richie, “Japan Shattered Stereotypes in the 60s,” The Japan Times, 9 October 2000. [↩]

- For a discussion of proto-Pop in the context of Japanese art, see Reiko Tomii, “Oiran Goes Pop: Contemporary Japanese Artists Reinventing Icons,” in Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri (eds), The World Goes Pop (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 95-103. [↩]

- Reiko Tomii, “Oiran Goes Pop: Contemporary Japanese Artists Reinventing Icons,” in Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri (eds), The World Goes Pop (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 103. [↩]

- Anthology No. 1 is also known as Tokuten eizō which has been translated as Privileged Images. Kachi kachi yama meoto no sujimichi has been translated as Creaking Mountain, The Couples’ Precepts and as Hermetic Prison – A Couple’s Home Education. See:

Maria Roberta Novielli, Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation (Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), 51.

Doryun Chong (ed.), Tokyo, 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 212. [↩] - Christopher Mount, “Japan’s Greatest Avant-Garde Artist,” in Masahiro Yasugi (ed.), The Complete Posters: Tadanori Yokoo (Japan: Kokushokankokai, 2010), 448. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Hiroko Ikegami, “‘Drink More?’ ‘No Thanks!’: The Spirit of Tokyo Pop,” in Darsie Alexander and Bartholomew Ryan (eds), International Pop (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015), 174. [↩] [↩]

- Hiroko Ikegami, “‘Drink More?’ ‘No Thanks!’: The Spirit of Tokyo Pop,” in Darsie Alexander and Bartholomew Ryan (eds), International Pop (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015), 174. Original text in Japanese. [↩]

- Steven C. Ridgely, “Total Immersion: Steven Ridgely on the Design of Tadanori Yokoo,” ArtForum 51.6 (February 2013): 207. [↩]

- Steven C. Ridgely, “Total Immersion: Steven Ridgely on the Design of Tadanori Yokoo,” ArtForum 51.6 (February 2013): 207-8. [↩]

- For example, some of the elements from Yokoo’s 1963 poster Kyoto Ro-on Concerts, Series B, No. 33 ( J. Fujio & T. Watanabe and Habana Cuban Boys) are re-configured and put into motion. Details from the actual poster are also shown in the film. [↩]

- Yuriko Furuhata, “Animating Copies: Japanese Graphic Design, the Xerox Machine, and Walter Benjamin,” in Karen Redrobe Beckman (ed.), Animating Film Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 184. [↩]

- Yuriko Furuhata, “Animating Copies: Japanese Graphic Design, the Xerox Machine, and Walter Benjamin,” in Karen Redrobe Beckman (ed.), Animating Film Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 185. [↩] [↩]

- Gekidan Mingei (The People’s Art Theatre) was formed in 1950 by Jūkichi Uno. Under the Magnolia Tree is a play by Yushi Koyama. [↩]

- Yokoo states, “as with Tadanori Yokoo [Made in Japan], these works [in his 1968 book Isakushu (Posthumous Works)] represented a form of rebirth for me.” Ashley Rawlings, “Dark was the Night,” Art and AsiaPacific, 74 (2011): 104. [↩]

- The kiss sound is a segment of the Dean Martin song recorded in reverse. Hiroko Ikegami, “‘Drink More?’ ‘No Thanks!’: The Spirit of Tokyo Pop,” in Darsie Alexander and Bartholomew Ryan (eds), International Pop (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015), 362. [↩]

- Tadanori Yokoo, Haran E!! Yokoo Tadanori Jiden (Tokyo: Bunshun Bunko, 1998), 85. [↩]

- John Coplans, Roy Lichtenstein (New York: Praeger, 1972), 52. [↩]

- For instance, see: Dorthy Seiberling, “Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?,” Life 56.5 (31 January 1965): 79–83; Doug McClellan, “Roy Lichtenstein, Ferus Gallery,” Artforum, 2.1 (July 1963): 44–47; Michael Lobel, Image Duplicator: Roy Lichtenstein and the Emergence of Pop Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003). The critics Brian O’Doherty and Erle Loran found it absurd that others were defending Lichtenstein by stating that he “transformed” rather than copied his sources since this went against the Pop spirit and artistic appropriation which already had a long-standing history within the arts. See David Deitcher, “Unsentimental Education: The Professionalization of the Artist,” in Graham Bader (ed.), Roy Lichtenstein (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008), 73–102. [↩]

- Yuriko Furuhata, “Animating Copies: Japanese Graphic Design, the Xerox Machine, and Walter Benjamin,” in Karen Redrobe Beckman (ed.), Animating Film Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 184-5. Translation by Furuhata. [↩]

- John Canaday, “Pop Art Sells On and On – Why?” New York Times Magazine (May 31, 1964): 7, 48 & 52–3. For more on the re-commodification of Lichtenstein’s appropriation style, see: Cécile Whiting, “Borrowed Spots: The Gendering of Comic Books, Lichtenstein’s Paintings, and Dishwasher Detergent,” American Art 6.2 (1992): 9–35. [↩]

- For more on how Pop art migrated through different spheres, see: Thomas Crow, “The Absconded Subject of Pop,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 55/56 (Spring-Autumn 2009): 5–16. [↩]

- Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 (New York: Scribner, 1990), 118. [↩]

- “The Vitascope at Keith’s,” Boston Herald (19 May 1896): 9. See: Charles Musser, “The May Irwin Kiss: Performance and the Beginnings of Cinema,” in Vanessa Toulmin and Simon Popple (eds), Visual Delights Two: Exhibition and Reception (London: John Libbey, 2005), 103. [↩]

- John Sloan, “Notes,” The Chap-book 5.5 (15 July 1896): 240. Emphasis in the original. The remarks are unsigned and have often been attributed to the editor Herbert Stone; however, they were actually written by the painter John Sloan. See Linda Williams, Screening Sex (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 331. [↩]

- Linda Williams, Screening Sex (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 26. [↩]

- Stephen Koch, Stargazer: Andy Warhol’s World and His Films (New York: Praeger, 1973), 36. [↩]

- For more information about Kiss including cast, crew and a reel-by-reel breakdown, see Bruce Jenkins, “Kiss,” in John G. Hanhardt (ed.), The Films of Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, 1963–1965 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021): 67–77. [↩]

- J. J. Murphy, The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 23–24. [↩]

- “Their smiles and glances and expressive gestures and the final joyous, over-powering, luscious osculation was repeated again and again, while the audience fairly shrieked and howled approval.” Los Angeles Times (7 July 1896): 6. See: Charles Musser, “The May Irwin Kiss: Performance and the Beginnings of Cinema,” in Vanessa Toulmin and Simon Popple (eds), Visual Delights Two: Exhibition and Reception (London: John Libbey, 2005), 104. [↩]

- Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel, Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art (Bologna: Damiani, 2011), 176. [↩] [↩]

- Andy Warhol, “Andy Warhol Interviewed by K. H.,” in Mark Francis and Margery King (eds), The Warhol Look: Glamour Style Fashion (Pittsburgh: Bullfinch Press and the Andy Warhol Museum, 1997), 273. [↩]

- Takayo Iida, “An Interview with Tadanori Yokoo,” in Sophie Perceval (ed.), Tadanori Yokoo (Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2006), 120. [↩]

- Steven C. Ridgely, “Total Immersion: Steven Ridgely on the Design of Tadanori Yokoo,” ArtForum 51.6 (February 2013): 206. [↩]

- On a side note, in 1967 Ōshima directed Ninja Bugei-chō (Band of Ninja), a film that took the remediation style of KISS KISS KISS to its logical conclusion. The film brought Sanpei Shirato’s popular manga to life by shooting the original illustrations (complete with speech bubbles and onomatopoeia) and adding a soundtrack with music, sound effects and voice. [↩]

- Joan Mellen, Voices from the Japanese Cinema (New York: Liveright, 1975), 271. [↩]

- Takayo Iida, ‘An Interview with Tadanori Yokoo’, in Sophie Perceval (ed.), Tadanori Yokoo (Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2006), 121. Yokoo explains: “[Ōshima] was the king of improvisation [ … ] it was through those untimely improvisations that the actors’ real personalities emerged and took on more depth.” [↩]

- Tadahito Nadamoto et al., Nihon Minwa Gurafikku (Japan: Bijutsu Shuppansha, 1964). The title of the graphic story is “Kachikachiyama.” Pairings included: Tadahito Nadamoto / Toshiyuki Takirai, Kazumasa Nagai / Yusuke Kaji, Akira Uno / Yusuke Kaji, Ikko Tanaka / Hiroshi Sakagami and Tadanori Yokoo / Mutsuo Takahashi. [↩]

- Kachi Kachi is onomatopoeia for the sound made when using flint to light a fire. [↩]

- For a discussion of manga (Japanese comics or graphic novels) as proto-Pop and its relationship to Pop art, see: Ryan Holmberg, “When Manga was Pop,” Art in America (January 2016): 56–63. [↩]

- Hiroko Ikeda, “‘Kachi-Kachi Mountain’ – An Animal Tale Cycle,” in Wayland D. Hand, Archer Taylor and Gustave O. Arlt (eds), Humaniora: Essays in Literature, Folklore, Bibliography Honoring Archer Taylor on His Seventieth Birthday, (Locust Valley: J. J. Augustin, 1960), 230. Lighting the badger on fire is a version of kugatachi, a trial in which the innocence of a person is judged by the divine will. In other words, if the badger were innocent, it would not burn. [↩]

- Lucrezia Morellato, “Symbolic Violence in Contemporary Japanese Children’s Literature: Case Study of a Japanese Folktale in Its Twenty-First Century Picture Books Renditions,” Master’s thesis, Lund University (2016): 23. [↩]

- Lucrezia Morellato, “Symbolic Violence in Contemporary Japanese Children’s Literature: Case Study of a Japanese Folktale in Its Twenty-First Century Picture Books Renditions,” Master’s thesis, Lund University (2016): 24. [↩]

- The funeral note also appears in the graphic story behind Delon who is sitting with Bardot on the bullet train, which features the rising sun in its window. Funeral notes usually have the name of the deceased in the middle; however, these ones do not, making them ominous and foreboding. [↩]

- Tadanori Yokoo, Haran E!! Yokoo Tadanori Jiden (Tokyo: Bunshun Bunko, 1998), 87. [↩]

- Bōbō is onomatopoeia for the sound made when something is vigorously burning. [↩]

- Translation by Aya Aikawa. [↩]

- Tadanori Yokoo, Haran E!! Yokoo Tadanori Jiden (Tokyo: Bunshun Bunko, 1998), 88. [↩]

- This is a well-known Buddhist sutra. [↩]

- Norman Hathaway and Dan Nadel, Electrical Banana: Masters of Psychedelic Art (Bologna: Damiani, 2011), 177. [↩]

- Hiroko Ikegami, “‘Drink More?’ ‘No Thanks!’: The Spirit of Tokyo Pop,” in Darsie Alexander and Bartholomew Ryan (eds), International Pop (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015), 176 & 180. [↩]

- In 1969, Toshi Ichiyanagi would again collaborate with Yokoo on Opera “From the Works of Tadanori Yokoo,” a two-LP picture disc set, which sonically blended musique conrète, Brechtian folk songs, field recordings and heavy psych rock. The set was designed by Yokoo and came with a four-page booklet containing twenty-four of his posters. [↩]

- Translation by Aya Aikawa. Translator note: It is written “infinite hell,” but this can be seen as wordplay on “Avici hell” since they are pronounced the same. [↩]

- ((Steven C. Ridgely, “Total Immersion: Steven Ridgely on the Design of Tadanori Yokoo,” ArtForum 51.6 (February 2013): 204. Ridgely adds that “they already had a global following, so the sleeper-cell structure was already in place.” [↩]

- For a well-researched account of the organising of the Tokyo component of the peace campaign, see Kevin Concannon, “War Is Over! John and Yoko’s Christmas Eve Happening, Tokyo, 1969,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 17 (December 2005): 72–85. [↩]

- Charles Childs, “Penthouse Interview: John and Yoko Lennon,” Penthouse 4.9 (October 1969): 29 & 34. [↩]

- John Lennon and Yoko Ono being interviewed by Niek Heizenberg for NCRV television (“Hier en Nu” programme), filmed on 25 March 1969. [↩]

- Ashley Rawlings, “Dark was the Night,” Art and AsiaPacific, 74 (2011): 104. [↩]