The work in Post-Cinema comes out of academic research and can be seen as an intersection between academic investigation and artistic experimentation. These works were created in an attempt to gain insight into some of the following questions:

What happens when cinema is reduced to a series of stills?

What is cinema without time?

What lies in the boundary between the photographic and the cinematic?

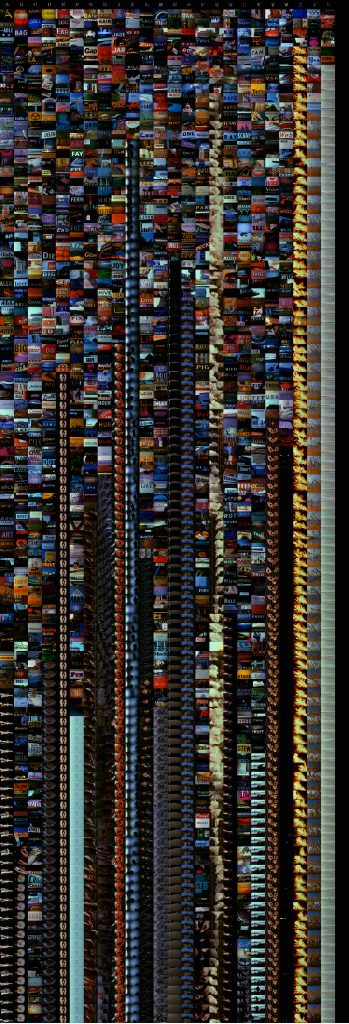

Michael Snow re-made his 45-minute seminal film Wavelength (1967) in an attempt to make it more accessible. The result was WVLNT (or Wavelength For Those Who Don’t Have the Time) (2003) a much shorter version of the original. The original film is a sequence of images revealed (and hidden) over time, a systematic form of photographic peek-a-boo, while Wavelength Without the Time (2013) condenses the film into a single image, in essence, removing cinematic time entirely from the equation. Taking a globalized view of the film exposes various aspects of the original film and its production. For instance, it is possible to see the overall colour palette Snow used in the production of the film (through the use of coloured gels, colour inversion and aperture changes). It is also possible to see Snow’s improvisational approach to the work. Although the film is structured around the zoom, Snow plays and improves with all of the other aspects of the cinematic apparatus, similar to the ways in which one makes improvised music.

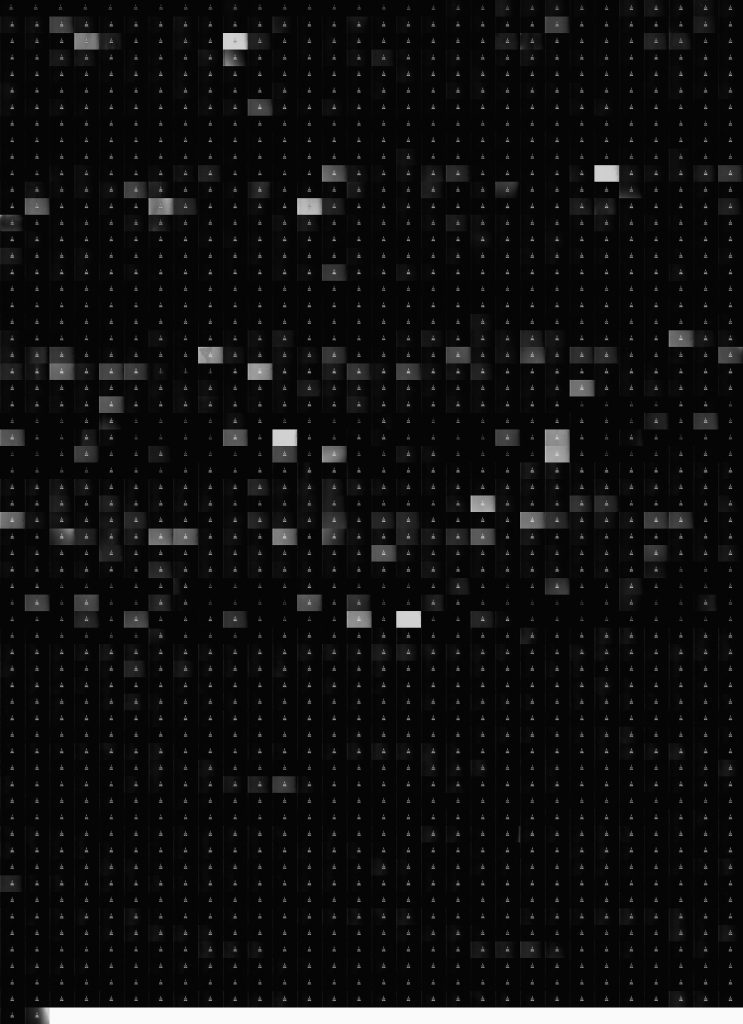

In a similar vein, Empire (abridged) (2012) is a photographic rendition of a 60 minute abridged version of Andy Warhol’s eight hour film Empire (1964) released in Italy in 2000 in association with the Andy Warhol Museum. In essence, a supposedly unwatchable film – the very unwatchability of the film is one of the reasons the film was created – is reduced to a photographic image.

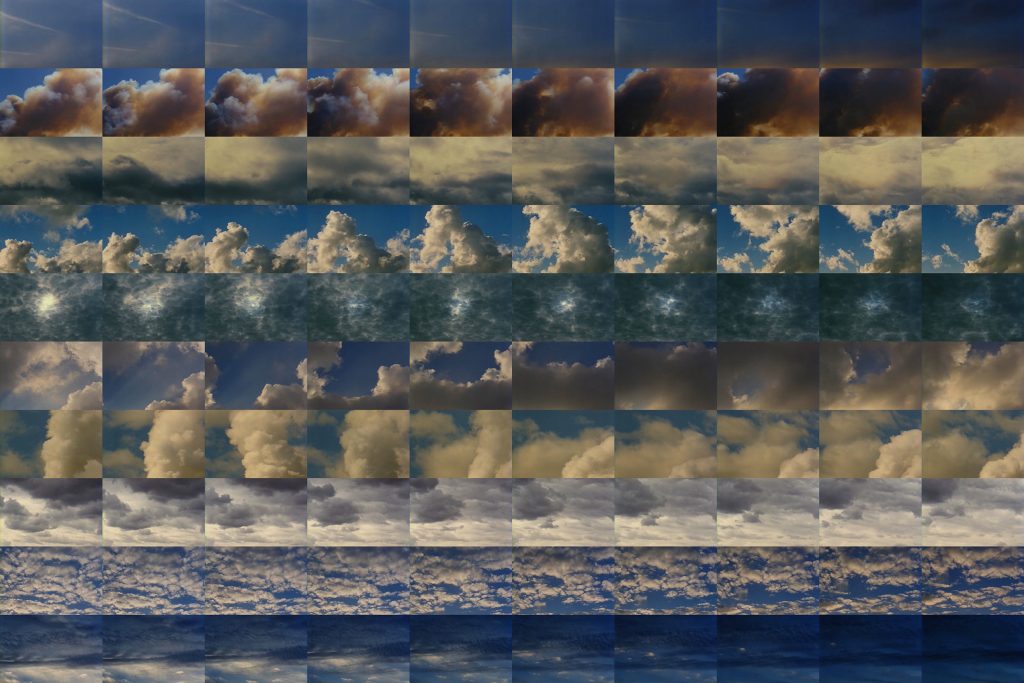

Ten X Ten Skies (2012) is a photograph made from James Benning’s film Ten Skies (2004). In Benning’s film ten skies are shot for a duration of ten minutes. Each line of Ten X Ten Skies represents 10 minutes of Benning’s film. The result is ten lines capturing all ten of Benning’s skies.

In Zorns Lemma (2012), a photographic montage, organized by lexicographical ordering is used to reveal the underlying structure of the second section of Hollis Frampton’s Zorn Lemma (1970). Similarly, Rope (2012) uses photographic montage to reveal all of the cuts in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) among other things.

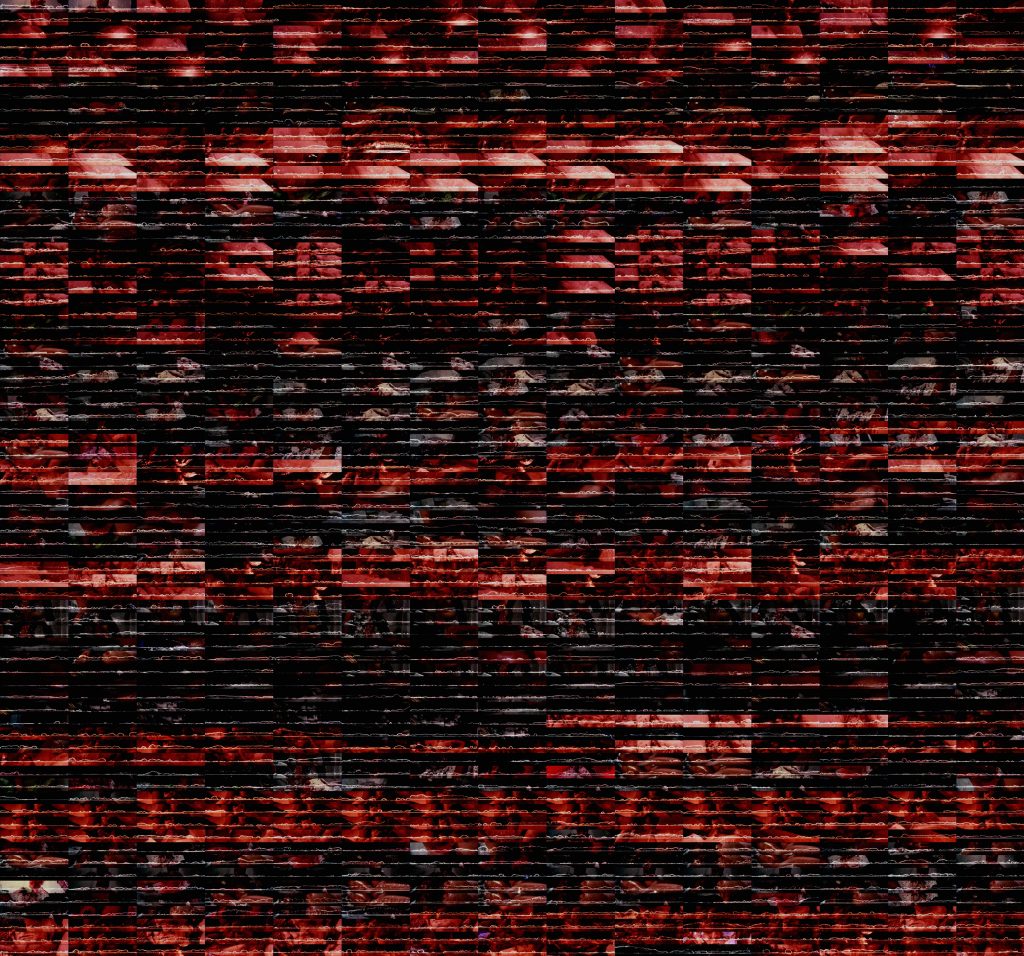

Finally, Splices Lines (2012) examines the splices in Kurt Kren’s 6/64: Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Mühl)(1964). The splices in the original film seem to enhance the violence of Kurt Kren’s film, a film documenting a performance where Otto Mühl smears various liquids including blood and urine on a nude performer. Removing them from this context seems to reveal the chaotic nature hidden within Kren’s mathematically precise system of editing.

Other Post-Cinematic Explorations

Panoramas

In the digital era, a moving image artwork can easily be transformed into a large database of sequentially ordered images. By viewing an artwork as large database of ordered photographic images, it is possible for the viewer to engage with the original work in entirely different ways, in essence, it opens up the artwork to new forms of manipulation and visual analysis.

Using an approach different from the image montage, Mike’s No [Interior/Exterior] (2015) are rough sketches that attempt to recreate the spaces in which Snow shot <—> (1969). The work is a panorama created by meticulously stitching together individual frames from the film that were obtained from a digitized VHS bootleg of the work. What was once a time-based, experimental film is now a landscape that does not exist in its entirety at any time in the film itself.

Expanding on the techniques developed for this project, All My Life (2016) is a digital panorama derived from Bruce Bailie’s 1966 film of the same name. This digitally-constructed panorama reveals a landscape that only occurs through a digital reconstruction of the film, the work exists in an interstitial space somewhere between filmic and photographic image.

While attempting to create this panorama, I accidentally produced a glitchy digital landscape that seemed to sort the original film by colour while maintaining the structure of the fence and power lines. The image produced was much too large to digitally manipulate; however, I created All My Life (After Bailie) (2016) by animating the glitchy digital landscape on single roll of Super 8.

Two Experiments

John Porter’s T-Shirt Collection

Zapruder Footage

Exhibitions

March 8 – April 5, 2013. “Post-Cinema.” Post-Cinema: Still and Moving Images by Clint Enns. Presented by Video Pool Media Arts Centre at aceartinc. in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Critical Discourse

All My Life

“All My Life.” Digital America 8 (December 6, 2016).

All My Life, Clint Enns’ digital panorama piece, derived from from Bruce Bailie’s 1966 film also titled All My Life, is an experimental digital display of the archive. The piece recreates an image made up of individual stills from the film meticulously stitched together. Enns describes the piece as “post-cinema,” and as “existing in the space somewhere between film and still image.” The panorama is a mystifying found-footage landscape of cinematic nostalgia, created anew. What was once a time-based, experimental film is transformed into a landscape that never existed in the film itself. The image’s exploded nature allows opens up a new world of possibility, creating something surreal and embedded with the poetics and simplicity of Bailie’s films. This digitally-constructed panorama reveals a landscape that can only occur through the digital reconstruction of the film—it exists in an interstitial space between film and image, landscape and .jpeg.

Subtractive Cinema

Tom Kohut, “Subtractive Cinema: Clint Enns,” BlackFlash 30.3 (September 2013): 8-11.

Filmmaker, new media artist, curator, critic and mathematician — Clint Enns’ status as Canadian underground and experimental film’s polymath is assured after nearly a decade of tireless enthusiasm and practice. Enns has been described as a practitioner of “Prairie Minimalism.” Few of his films and videos are much more than two or three minutes in length, and they are marked by their formalism and adventurous use of outmoded and/or malfunctioning technologies to produce work that demonstrates wit, aesthetic and conceptual sophistication in addition to a certain ambivalence to the history of his medium: a certain mix of admiration and derision that is, perhaps, the mark of true cinephiles in their love of Cinema’s potential and their disappointed anger when it fails to live up to its own ideals.

Having explored such fields as repurposed found footage and distressed video games and cameras, Enns has recently taken an interest in the history of algorithmic filmmaking — an approach that applies a strict formalization to the production of moving images and sound.”1 The results of this engagement were recently shown at the AceArt Flux Space in Winnipeg. Enns’ “Post Cinema: Still and Moving Images” asks a number of questions about the ontology of the cinematic image, a task that puts Enns firmly in the tradition extending from Dziga Vertov to Jean-Luc Godard who explored the question of the specificity of the filmed image, its relation to sound and text, its essential mode of being.2 Enns makes use of paradigmatic works in the history of algorithmic filmmaking: Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), Kurt Kren’s 1964 short Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Miihl), Warhol’s Empire (1964), the second section of Hollis Frampton’s Zorn Lemma (1970), Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and the most recent film, James Benning’s Ten Skies (2004). All of these films are notable in their deliberate foregrounding of their editing structures; even the most straightforwardly narrative film (Rope) is infamous in cinematic circles for Hitchcock’s attempt/stunt to make the film appear to be shot in a single continusous take. (In reality, as every Hitchcock fan knows, there are ten takes of ten minutes in length, each disguised by an artful dodge behind a character’s back or through a close-up on a piece of furniture.)3 So wehave the postulation of a living canon, delineated as a sort of diagonal through Hollywood cinema, the American (and Canadian) Underground, Viennese actionism and contemporary digital filmmaking.

What does Enns contribute to this canon? A notable subtraction: Enns appropriates these films in order to produce two videos and six photographs that form the focus of the “Post Cinema” exhibition. In his artist statement, Enns asks: “What happens when cinema is reduced to a series of stills? What is cinema without time? What lies in the boundary between the photographic and the cinematic?” The question is a subtle one but also one that goes to the heart of the question of what a cinematic image is. For cinema is nothing if not a durational, diachronic art, one that enfolds in time; to paraphrase Godard, film marks its time from beginning, middle to end (if not necessarily in that order). Even these films, which flaunt their replacement of narrative structure with algorithmic process, may be said to replace narrative diachrony with what might be referred to as cinematic diachrony; their duration depends on nothing other than the time it takes to run the film, rather than any extraneous detail such as introduction, build-up or climax.

Enns’ subtractive strategy develops along two modes manifested differently in the videos and the photographs. For the videos, Enns subtracts key focal elements of Kren and Benning’s films; in the case of the former, the film’s subject — a typically violent Otto Muhl “action,” bodily fluids and all — is removed, retaining only Kren’s splice lines.4 The result is a video of red, yellow and black abstract lines moving across the screen, connoting an impressive violence in themselves. For Benning’s more lyrical evocation of Ten Skies, Enns actually removes the image of the skies themselves, leaving only the movement of cloud patterns that also take on a curiously disjointed aspect. Enns refers to this strategy as condensation,5 the result of which is a drastically abbreviated version of a longer, meditative work.6 In both cases, what subtraction means is clear: a reduction of the cinematic field to figure without ground (in the case of the Benning-related video Ten Skies) and, in the case of the Kren work Splice Lines, a statement that there is no cinema that does not ontologically derive from the editing splice — the cut.7

If the cut is foregrounded in the video work, what kind of subtractive strategy does Enns employ in his photographic works? The six works are, at first glance, very similar: a grid of small squares arranged as a mosaic. Adapting Open Source software designed by Lev Manovich,8 Enns created a database of all of the frames in the films in question; using the software’s algorithms, Enns generated a selection of the images arranged in grids. The printed results are what we see: a determinate number of square films stills arranged chronologically, sometimes horizontally or, as in the case of Zorns Lemma (2012), vertically. This last example is particularly interesting, insofar as it neatly encapsulates the import of Enns’ work. On the one hand, we are able to take in the entire film (in fact, the second half) in a single glance, appreciating gradations in colour and form. On the other hand, we are able to grasp the algorithmic nature of the film, with its alphabetical frames, noting where this rigour is contaminated by seemingly aleatory shots of faces and activities. The colour and form of the film is emphasized by the minuteness of the individual frames; even Warhol’s black and white minimalist Empire, in Clint Enns’s hands, Empire (abridged) (2012) benefits from this treatment, the grid like repetition of the Empire State building coming to resemble the regal stamp of a monarchy in terminal decline — indeed, a decayed empire.

Enns has clearly subtracted diachrony — the movement of time — from these films in favour of the synchronic relation of spatial location. In this sense, he has generated films that can be viewed in their entirety instantaneously. But there is something further to add, something that we can articulate by looking at the use he makes of Michael Snow’s iconic Wavelength. There are, in fact, two versions of Snow’s 1967 landmark film: the original version and a version produced by the author in 2003, WVLNT (or Wavelength for Those Who Don’t Have the Time).9 The original, 45-minute version is well-known; the second 15-minute, accelerated version is, for the most part, the original version split into three 15-minute blocks which are superimposed onto each other. In both cases, the sense of film as the succession of instants is highly attenuated, although not, it should be emphasized, completely exhausted. In the 1967 version, it is true that the zoom across the room is slow to the point of near imperceptibility, but there remains what might be called “the time of the zoom.”10 Day is followed by night; the man (Hollis Frampton) who enters the shot and dies, before the zoom passes over him, nevertheless precedes the woman’s telephone call to her friend reporting the incident. The situation is complicated in WVLNT in which we have three different temporal successions overlayed onto each other. (Amusingly, the woman’s telephone call actually precedes Frampton’s expiration on the floor in this later version.) These attenuations are Snow’s attempt to examine the precise delimitation of photography from film, finding that even the most minimal difference in diachrony allows film to become its own notion; the photograph of the waves on which the zoom rests at the end of Wavelength might be said to function as a gauntlet thrown down by space in the face of time. This gauntlet is taken up by Enns’ Wavelength Without Time (2012). A few things are happening here. Firstly, there is an element of film analysis, that is, a (nearly) frame-by-frame examination of the 1967 film for which the term “structural cinema” was invented.11 Hence, a further pedagogical effect: viewers are able to appreciate the blends of coloured gels, afterimages, the composition of the shots — in short, all of the “fine art” aspects to Snow’s film, whose visual pleasure is the source of the colourful mosaic of the Enns photograph’s own visual pleasure. However, there is a further point to be made. Enns subtracts diachrony from Wavelength (whose attenuated sense of temporal progression perhaps made it slightly easier for Enns to do). What we are left with, then, is a diachronic progression rendered as a synchronic totality. If with the films, Enns’ subtractive strategy served to isolate the ontological substrate of film as the editing splice, with the photographs, the subtraction of synchrony serves to foreground the structuration of these splices as the ontological essence of film itself. In effect, Enns’s work enables us to see that film is a structure of cuts, of sutured gaps, prior to any phenomenological aftereffect. And I would argue something further: if the experience of film is coextensive with the experience of time, Enns’s work asks a troubling question: what if the human experience of time is in fact nothing more than the local effect of a determinate structure of images?

- Clint Enns, “Charting the Montage: The Roots of Algorithmic Cinema,” Marshall McLuhan + Vilém Flusser’s Communication + Aesthetic Theories Revisited, edited by Melentie Pandilovski and Tom Kohut (Winnipeg: Video Pool Media Arts Centre, 2015), 155-62. [↩]

- More recently, this project has been taken on by the Winnipeg/Montreal filmmaker Isiah Medina in his films Semi-Auto Colours (2011) and Le boulet n’est pas passé loin (2013), among others. [↩]

- D. A. Miller usefully schematizes these hidden edits in his psychoanalytic essay “Anal Rope,” in Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories (London: Routledge, 1991) 141, f.18. [↩]

- Kren’s film is more than just performance documentation, but a heavily edited work that is at the very least a relatively autonomous work of art. Kren’s edits were numerous but rather crudely executed, leading the filmmaker to fear that his film would not survive laboratory processing. According to legend, this was the least of his worries; the lab technicians, so disturbed by what they saw, gave him his film back and told him to leave the premises and never come back. [↩]

- E-mail correspondence with the author dated May, 29 2013. [↩]

- Benning’s original film is just under two hours in length; Enns’s distillation clocks in at a brisk three minutes, although this is positively encyclopaedic by Enns’s standards. [↩]

- In fact, the same may be said of Enns’ reworked Benning film. By accelerating the movement of the clouds, Enns interrupts the smooth flow of the original film, thereby making the edits abruptly apparent. [↩]

- Software available here. This software is designed to enable data visualization for film and video collections and databases, and is part of Manovich’s shift from new media studies to the avant-gardism of software design itself. Lev Manovich, Software Takes Command (New York, Bloomsbury, 2013). [↩]

- In this context, it should be noted that the version of Empire that Enns used to generate Empire (abridged) is not the eight-hour version originally shot by Warhol in 1964, but rather an hour-long version released in Italy in association with the Andy Warhol Museum. I also offer a somewhat heretical opinion: I slightly prefer WVLNT to Wavelength. [↩]

- In Deleuze’s Cinema books, his brief discussion of Wavelength is found in the first volume concerning The Movement-Image, noting its exhaustion of the real space of the room in order to produce a generic “any-space-whatever”. Giles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minnesota: University of Minneapolis Press, 1986), 122. [↩]

- In the chapter on “Structural Film,” Sitney, who coined the term, states that “Wavelength may be the supreme achievement of the form….” P. Adams Sitney, Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde 1943 – 2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002). [↩]