“Images Beyond Time: Cinema as Photographic Archive.” Found Footage Magazine 2 (May 2016): 44-53.

What is astonishing with each and every photograph

Wim Wenders, Once: Pictures and Stories

is not so much that it “freezes time”

—as people commonly think—

but that on the contrary

time proves with every picture anew

HOW unstoppable and perpetual it is.1

Some previous strategies within experimental cinema have been to use photographs to explore tensions between the photographic and the cinematic (for instance, Michael Snow’s One Second in Montreal (1969)), to investigate the photographic image’s indexical relationship to the past (as in, Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962)), and to create space for the viewer to examine and deconstruct various elements within the image (see: Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Letter to Jane (1972)). In this brief essay, I will explore three additional categories of cinematic works that experiment with the relationship between cinema and the photographic archive. In the first section of this essay, I will examine the ways in which experimental films use photographic archives in order to prevent their death-by-dormancy, that is, the death that occurs when an object enters an archive and is never heard from again, forever imprisoned in an acid-free, cardboard coffin. As observed by Bruno Bachimont, director of research at the French National Audiovisual Institute, “we only conserve well what we use.”2 Moreover, I will explore some of the connections between these works and aspects of Derrida’s concept of archive fever presented in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. In the second section of this essay, I will examine cinematic works that engage with the underlying photographic archive hidden within each motion picture film—namely, the large number of ordered photographic still images that, when set in motion, constitute a motion picture film. In the last section of this essay, I will explore moving image works that can be seen as a formal inversion of the film as a collection of still images, namely, moving images that are transformed into a still image.3 That is, I will analyze works that use the visual nature of the photographic archive inherent within moving images to create still images.

Stills-as-Cinema: The Photographic Archive as Cinema

In 1971, American avant-garde filmmaker Hollis Frampton released (nostalgia) a canonical experimental film in which photographs are burnt on a hotplate while the narrator—Toronto visual artist and musician Michael Snow—provides a description and an anecdote about the next image in the series. The photographs were taken in New York City and they are, for the most part, the artist’s own. Through the film, the past is literally made present and past memories are slowly destroyed by the coil of the hotplate. In this sense, the film seems to recall literary critic, philosopher and semiotician Roland Barthes’ meditation on the photographic image in Camera Lucida, namely, his insight that with photography there is a superimposition “of reality and of the past.”4

Frampton’s film reveals several shared intrinsic characteristics of both film and photography. For instance, the audience does not smell the image burning. In contrast, a live performance may produce the smell of the burning images, however, it would not preserve the ephemeral act of “burning” in the same way that cinema does. It is also worth observing that a photograph is incapable of capturing sound and that film literally has the ability to reproduce photographs. Frampton has remarked, “a picture is worth some large, but finite, amount of words.”5 In fact, this is one of the places in which Frampton diverges from Barthes who was perhaps suggesting something more interesting, that is, that a photograph contains something beyond language, something inherently beyond language. Film theorist Rachel Moore argues that Frampton is implicitly suggesting that cinema, in contrast to photography, contains an “infinite” word count, citing the connection Frampton makes between film and consciousness, a connection that is established through film’s ability to capture the passing of time.6 As Frampton scholar Bruce Jenkins explains:

The disjunction between sound and image, which continues throughout the film, engages the viewer in the process of recollection often associated with the photographic image, and liberalizes the idea of the photographic pretext that Frampton often invokes in describing the medium.7

Expanding on this observation, Frampton’s film is explicitly exploring the tension between presence/absence, past/present, and image/language both in terms of the photographs relation to the past and the context determined by the boundaries of the photograph.

Photography captures a moment in time, in essence, making it eternal. As filmmaker and photographer Wim Wenders observes, “and all that appears in front of the camera just ONCE (sic), and every photograph turns this once into an eternity.”8 In contrast, film itself is a performance that only lasts as long as the film is projected. Through this performance, the paradoxical nature of archive and its connection to the death drive, the self-destructive urge to return to the state before one’s birth, is formally realized because the projection of any film is a record of its own destruction. In The Death of Cinema, Paolo Cherchi-Usai argues that “cinema is the art of destroying moving images.”9 Cherchi-Usai observes that every time a film is run through a projector it becomes closer to its own death since film projection is a mechanical operation. As Derrida insists, “the archive always works, and a priori, against itself.”10 (nostalgia) confronts this paradox since the photographs are made eternal through their recorded destruction. In fact, it may even be possible to digitally restore Frampton’s photographic images using stills from the film. In this way, the film captures the fundamental paradox in Derrida’s concept of the archive as death drive, namely, the desire to both remember and forget. Furthermore, Frampton exhibits the violence associated with forgetting through the burning of the photographs. Of course, (nostalgia) is only a film. In real life, Frampton further complicates this tension by admitting he did not actually destroy his negatives. In an artist statement for (nostalgia), Frampton states:

So I decided, humanely, to destroy them [the photographs] (retaining the negatives, of course, against unpredictable future needs) by burning. My biographical film would be a document of this compassionate act.11

Frampton’s hyper-awareness about the secure status of his negatives further complicates the tensions between remembering and forgetting in the work and seemingly undermines the cathartic nature of the work.

memento mori (2012) by Toronto filmmaker Dan Browne, is another film that makes use of a personal photographic archive. Similar to Frampton who destroys his images in order to make them eternal, Browne animates his archive through superimposition, bringing them to life in order to prevent their death. Browne’s use of superimposition seems to destroy the original photographic images by compromising their indexical status and legibility through abstraction. Browne describes his work as “a meditation on (im)mortality, mediated by a lifetime of images.”12). The images in memento mori flicker on the screen creating the sensation of a near death experience in which your life instantaneously flashes before your eyes. The repetition of the images, the obsessive nature of the work, and the anxiety created due to the immensity and overwhelming nature of the archive used—a lifetime of images—seems to speak directly to Derrida’s description of what it means to suffer from archival fever:

It is to burn with passion. It is never to rest, interminably, from a searching for the archive right where it slips away. It is to run after the archive, even if there’s too much of it, right where something in it anarchives itself. It is to have a compulsive, repetitive, and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement.13

On the one hand, “to ‘burn’ with passion,” could easily serve as a synopsis for Frampton’s film. The burning photos also suggests the archive as death drive in a Derridean sense. To Derrida, “the death drive is above all ‘anarchivic’, one could say, or ‘archiviolithic.’ It will have been archive-destroying, by silent vocation.”14 On the other hand, if Frampton is suffering from archival fever it is slightly different from Derrida’s conceptualization since Frampton does not view nostalgia as a form of longing. Frampton describes nostalgia as follows:

In Greek the word [nostalgia] means “the wounds of returning.” Nostalgia is not an emotion that is entertained; it is sustained. When Ulysses comes home, nostalgia is the lumps he takes, not the tremulous pleasures he derives from being home again.15

To Frampton, nostalgia is not the desire to return home, but of the wounds gathered while returning. Combing both Derrida and Frampton’s concepts of nostalgia suggests a penultimate form of nostalgia, namely, the metaphysical concept that one’s life flashes before their eyes when they die. This is the experience that Browne attempts to replicate in memento mori.

Cinema-as-Stills: Cinema as Photographic Archive

As demonstrated, the documentation of photographs is one way in which cinema can activate a photographic archive. Similarly, there are many works that explore the underlying photographic archive contained within a film, that is, the large imagistic cache, or database, of ordered images that make-up any film. Viewing films as large databases of photographic images allows the viewer to engage with the film in a different way, providing new insight into the films themselves and tracing out the boundary between the cinematic and the photographic.

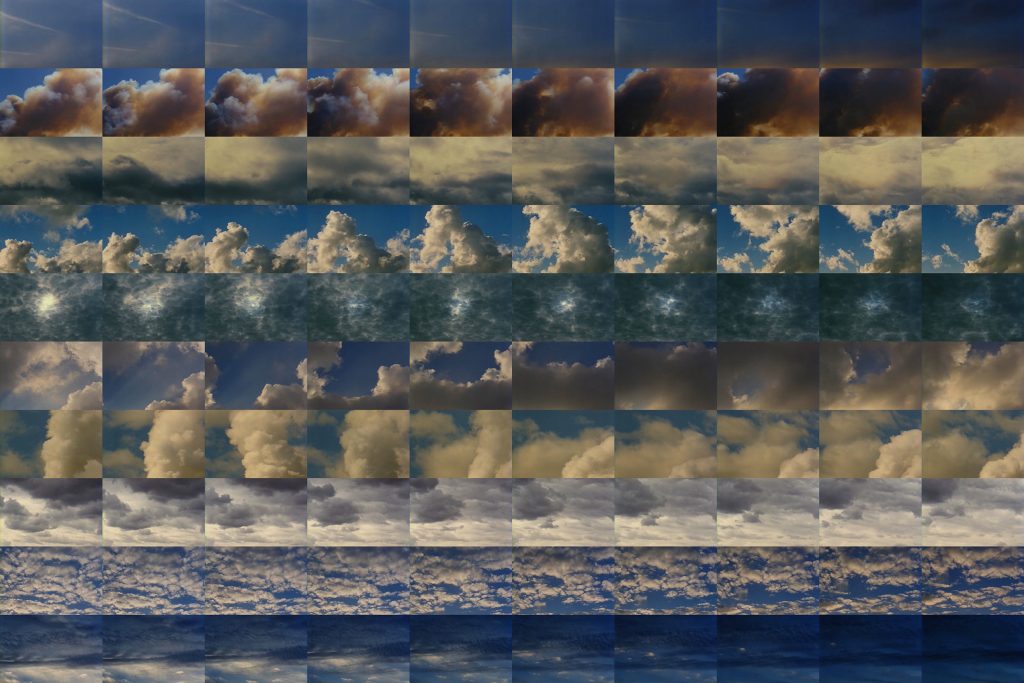

My own research series Post-Cinema is one attempt at exploring films as a large archive of photographic images. In the series, films are reduced to large photographic montages in order to provide new insight into the film itself. The series consists of six photo montages whose principles are grounded on found footage techniques: Wavelength Without the Timebased on Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967); Empire (abridged) based on Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964); Ten X Ten Skiesbased on James Benning’s Ten Skies (2004); Zorns Lemma based on Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970); Rope based on Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948); and Splice Lines based on Kurt Kren’s 6/64: Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Mühl) (1964).

Wavelength Without the Time is an attempt to bring Wavelength into the Post-Cinema era removing time entirely from the film, similar to Snow’s 2003 re-make WVLNT (Wavelength For Those Who Don’t Have the Time), a shorter and hence more accessible version of the original. The photo montage generated in Wavelength Without the Time explicitly reveals the color palette Snow used to create Wavelength and the improvised nature of the work. The organization of film stills into photo montages also makes evident many underlying structures within the original films. Ten X Ten Skies is a photograph made from Benning’s film Ten Skies. In Benning’s film ten skies are each shot for a duration of ten minutes. Each line of Ten X Ten Skies represents 10 minutes of Benning’s film. The result is ten lines capturing all ten of Benning’s skies. The photo montage for Frampton’s Zorns Lemma is organized by lexicographical ordering, revealing the complex underlying structure of the second section of the original film.

By examining photo montages constructed from a series of film stills, it is often possible to reveal the underlying editing structures of the original film. For instance, my photo montage for Rope reveals all of the hidden cuts in Hitchcock’s ostensibly continuous, one-shot film. Moreover, my photo montage Splices Lines explicitly examines the splices in Kren’s 6/64: Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Mühl), a film that documents Austrian performance artist Otto Mühl smearing various liquids including blood and urine on a nude performer. The splices in the film itself seems to enhance the violent nature of film. Removing the splices from their original context seems to reveal the chaotic nature hidden within Kren’s mathematically precise system of editing.

It is well established that Abraham Zapruder’s footage of the John F. Kennedy assassination is one of the most scrutinized pieces of film footage. On November 22, 1963 Zapruder captured the assassination of JFK on his Model 414 PD Bell & Howell Zoomatic Director Series Camera with Varamat 9 to 27mm F1.8 lens with 8mm Kodachrome II safety film.16 The footage of the assassination was shot at 18 frames per second, is 486 frames long, and runs for just under 27 seconds, forming one of the most controversial archives of photographic images ever recorded. Despite not being publicly available, until 1975 when it aired live on ABC’s Good Night America (hosted by infamous investigative journalist Geraldo Rivera), many of the individual frames were released as early as 1963 by Time magazine.

According to JFK assassination expert Martin Shackelford, by February 1969 unofficial bootlegs of the film began to circulate.17 The delay between the public release of Zapruder’s footage of the JFK assassination and its availability in underground circulation seems to have contributed to the idea that the official findings of the Warren Commission were a cover-up. Granting the public access to footage of this nature (and historical importance) inevitably leads to greater scrutiny and to a host of counter-interpretations, some more plausible than others. Every frame becomes crucial to piecing together an interpretation of the event and hence must be accounted for. For instance, Life magazine even issued a public statement on November 23, 1963 about four frames from the camera original that had been damaged by a photo-lab technician, demonstrating the importance of each frame of the film as a photographic archive.18 In fact, there are many digital reconstructions of these frames.

The possibility that the Zapruder footage ultimately holds the key to the Kennedy assassination is the promise of the archive. In other words, that this 486 frame photographic archive—this 27 second piece of cinema—holds in it the future truth of the past is the promise of the archive. To Derrida, “a spectral messianicity is at work in the concept of the archive and ties it, like religion, like history, like science itself, to a very singular experience of the promise.”19 This promise has been continually exploited in television and movies from Antonioni’s 1966 Blowup to the television trope of unlocking earth-shattering clues in videos and photographs by “enhancing” them. Arguably, this promise also contributes to constant drive for higher fidelity in image capturing devices. Moreover, the passion with which conspiracy theorists obsessively scrutinize the Zapruder footage is literally a vivid demonstration of what it is like to suffer from archival fever.

Cinema-as-Still: Beyond the Motion Picture

Cinema as a large archive of photographic stills has a natural formal inversion, namely, the still as a moving image. One of the earliest examples might be Paul Sharits’ Frozen Film Frame series (c. 1971–76), a series made up of strips of film suspended between sheets of Plexiglas. A more representational example is Peter Tscherkassky’s film/image Motion Picture: La Sortie des Ouvriers de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (1984) created by exposing 50 unexposed pieces of 16mm film to a projected image of one frame from Louise Lumière’s 1895 film La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon). The film can be viewed in two ways, as a moving image or as a still created by arranging the 16mm to form the Lumière frame. Tscherkassky’s film/image is intended to formally capture the tension between still and moving images. By using Lumière’s La Sortie de l’usine Lumière à Lyon, a film that is considered to be the first motion picture,20 Tscherkassky is implicitly referencing the transformation from still photography into moving images. The result is a work that is equally both a still and a moving image, further complicating the boundary between the two.

Another example of this formal inversion is Walter Forsberg’s Video Preservation (NTSC). In 2013, Forsberg created a tableau of the Society of Motion Picture & Television Engineers (SMPTE) split-field bars, the colour bars or television test pattern used to determine how an NTSC video signal has been altered by recording or transmission, using Kodak 7285 16mm colour reversal film. Forsberg explains:

Translating these voltage values into filmic form seemed immediately logical, especially once Kodak discontinued its colour reversal film stocks in late 2012. This occurred to me as one strategy to preserve standard definition video beyond the lifespan of its own magnetic media format. A light leak in the Bolex makes for something of a strange ‘dropout’ in the magenta region, and rendering the 80% gray bar as a filmed 18 gray card is supposed to be funny.21

In other words, the film is at once a comment on the archival life of video and on the limitations of any media. Moreover, the tableau itself produced through this process can easily be seen as a response to one of the solutions to contemporary archival problems, that is, sophisticated forms of transmedium transcoding. As such, the tableau itself with all its medium specific “flaws,” the sprocket holes and unexposed black image beyond the frame, provides a visual example of the potential information loss that can occur through transcoding. When the image of the SMPTE split-field bars is rendered on 16mm film, the information loss is immediately obvious. Moreover, one encounters an analogous problem when digitizing any form of visual information given the present state of the technology.

Finally, Izabella Pruska-Oldenhof’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (2008) has two components: a 16mm film component and a free standing photogram collage built from 16mm film, vegetable and animal debris, gold paint powder, Plexiglas and aluminum bolts. The photogram is a self-portrait and acts as a travelling matte in the film. In essence, Pruska-Oldenhof’s body forms the underlying rhythm of the film. Expanding on Bazin, the photogram of her body functions as a death mask formed by light. It is a preserved impression, at once graphic inscription, abstraction and mark left by Pruska-Oldenhof. The way in which the collage interweaves the impression of the body with the vegetable and animal debris—the flesh of the world—suggests “a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement”13 further connecting Pruska-Oldenhof’s collage to the longing associated with Derrida’s conception of archival fever.

Cinema is one of the ways in which artists bring the photographic archive to life. In particular, (nostalgia) and memento mori, are films that realize Derrida’s theory surrounding archival fever through cinema. In addition to cinema animating the photographic archive, cinema itself can be seen as a photographic archive. Nevertheless, viewing cinema simply as an ordered sequence of photographs removes one of the essential elements of cinema, namely, movement. Although something is lost in this reduction, it also provides another way of studying cinema, one that might provide valuable insight in terms of demystifying editing structures, composition, colour schemes, etc. In other words, they allow the spectator to view the film, the entire photographic database, as a single image. Moreover, the promise that a single film frame holds hidden secrets beyond our wildest imagination is ultimately the promise of Derrida’s concept of the archive. Finally, transforming single still images into moving images conceptually pushes the boundaries between still and moving images, and further demonstrates the archival tensions inherent in any medium.

The underlying ideas for this paper were formed in Janine Marchessault’s course Archive_Memory_Database at York University (Toronto, Canada). I am incredibly grateful for her support and advice. I would also like to thank Cameron Moneo and Walter Forsberg for their advice and critical suggestions.

- Wim Wenders, Once: Pictures and Stories, trans. Marion Kagerer (New York/Munich: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2001), 11. [↩]

- Quoted in Jean Gagnon, “The Time of the Audiovisual and Multimedia Archive,” trans. by Timothy Barnard, Public 44 (2011): 59. [↩]

- I am indebted to Martin Zeilinger who suggested that I pursue this formal inversion. [↩]

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 76. [↩]

- Hollis Frampton, “Erotic Predicaments for a Camera,” October No. 32 (Spring 1985): 56. This text was written in April 1982. [↩]

- Rachel Moore, Hollis Frampton: (nostalgia) (London: Afterall Books.), 5. [↩]

- Bruce Jenkins, On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters: The Writings of Hollis Frampton (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009), 209. [↩]

- Wenders, Once,15. [↩]

- Paolo Cherchi-Usai, The Death of Cinema: History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age (London: BFI Publishing, 2001), 7. [↩]

- Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 12. [↩]

- Hollis Frampton, “Notes on (nostalgia),” Film Culture Nos. 53-55 (Spring 1972): 11. This text was written in April 1971.

It is worth noting that Frampton encodes this idea in the text of the film itself: “I despised this photo for several years. But I never could bring myself to destroy a negative so incriminating.” For a complete transcript of the (nostalgia) see Film Culture, nos. 53-55 (Spring 1972): 105-111. This film script was written in January 1971. [↩] - Dan Browne, “memento mori (Artist Statement),” Dan Browne (2012 [↩]

- Derrida, Archive Fever, 91. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., 10. [↩]

- Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 60. [↩]

- Martin Shackelford, “A History of the Zapruder Film,” (updated by Debra Conway.), n.d. [↩]

- Shackelford, “A History of the Zapruder Film.” [↩]

- “Life to Release Today Part of Kennedy Film,” New York Times (January 30, 1967): 22. [↩]

- Derrida, Archive Fever, 36. [↩]

- Louis Le Prince’s 1888 Roundhay Garden Scene pre-dated it by seven years. [↩]

- Walter Forsberg, “Preservation Series.” (2013). [↩]