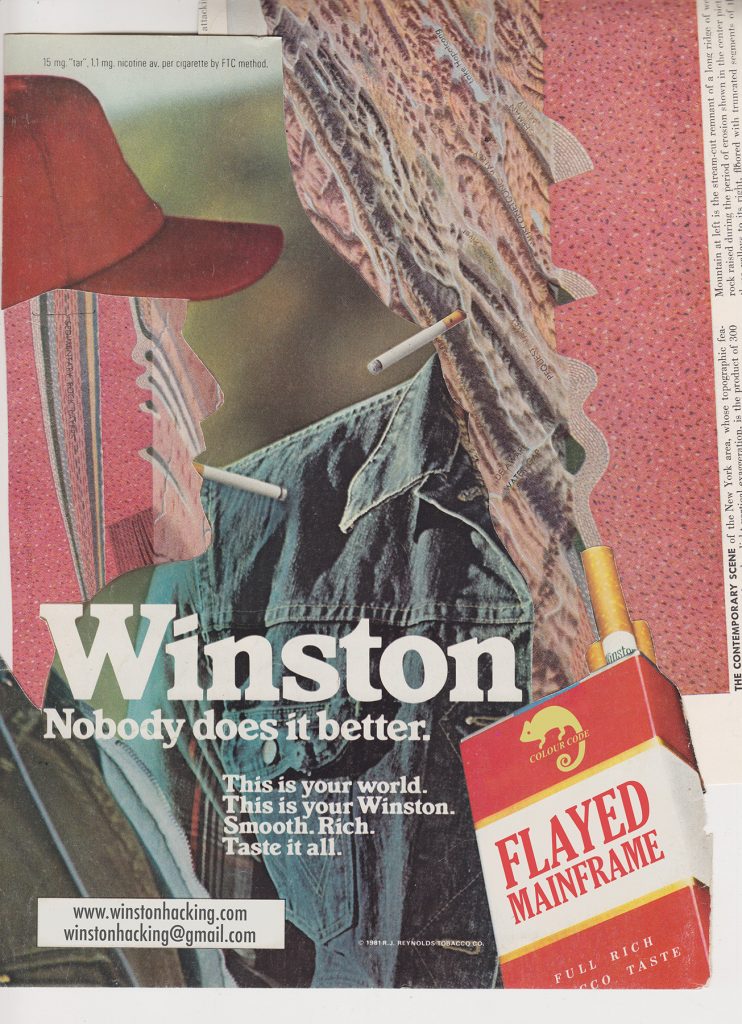

“Exploding Visions: An Interview with Winston Hacking.” Found Footage Magazine 4 (March 2018): 130-4.

Winston Hacking is a moving image artist originally from Peterborough, Ontario (Canada). His work is on the frontier of Canadian animation and often combines found footage, collage, green screen and puppeteering. Hacking’s work is economical, both in terms of his ingenious use of found materials and his technical innovation. Despite his thrifty approach, his works are daedal due to his ability to transform the mundane into the sublime through creative re-contextualization.

His most ambitious work to date, The Public Slaw (2015), co-directed with Andrew Zukerman, is a handcrafted, psychedelic vision that blends found footage experimental filmmaking techniques, Internet memes and public access television. The film is hosted by a public access Dracula (played by Kevin Leggat) who introduces the viewer to an onslaught of images including pugs, no-budget horror films, collages, and a news bulletin consisting of a falling cat landing on its feet, among other things, all of which are held together by a visual commentary in the form of direct animation. The final section of the film is a dance performance by Minae Omi that, together with chaotic camerawork and editing, creates a visceral experience that is bound to appeal to the audience’s innermost nihilistic impulses.

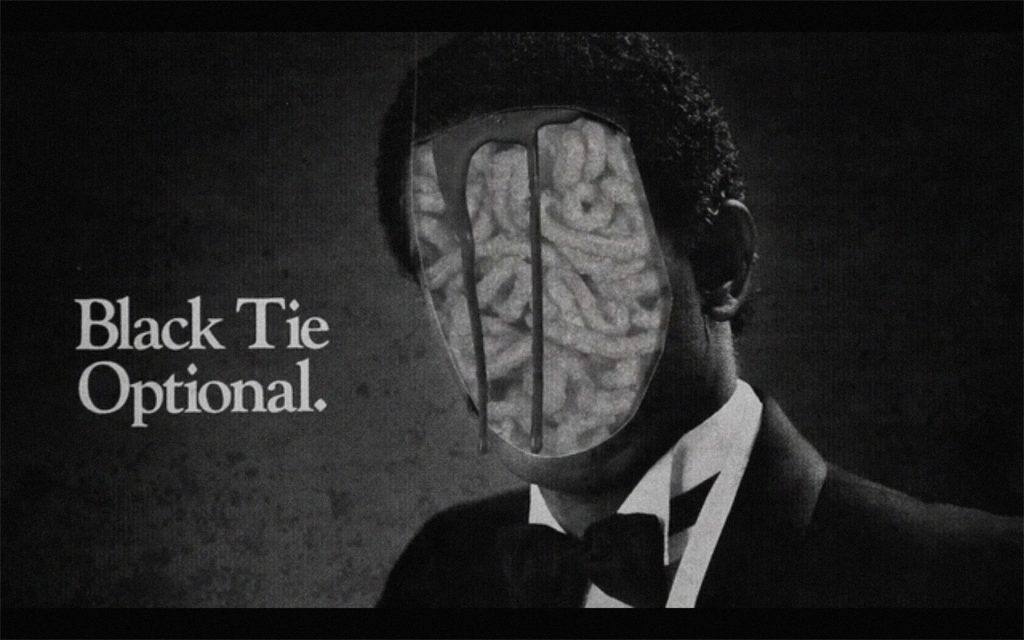

Hacking’s most recent music videos, for the Soupcans’ Siamese Brutality (2015) and for Andy Shauf’s The Magician (2016) and The Worst in You (2016), develop a technique he describes as “lazy paperteering.” This incredibly clever technique involves collage and green screening and, despite being relatively simple, yields sophisticated results. Hacking’s most recent project involved creating transitional moving collages for Flying Lotus’ controversial feature length horror film Kuso (2017).

This interview was conducted over e-mail and collaboratively edited into its current form.

Clint Enns: How did you begin animating?

Winston Hacking: To begin, I don’t think that I have actually animated anything, but let’s discuss techniques later. I studied Film and Television at Sheridan College where I developed my skills as a set builder and art director working on short, 16mm stop-motion films. Eventually, and somewhat unexpectedly, I ended up working in the stop-motion animation industry as a means of supporting myself, mainly as a set builder, set dresser and art director. I have always been fascinated with animation, but I was too intimidated by my talented peers to actually produce my own films.

CE: Perhaps this is one of the reasons that you often work collaboratively. Can you talk about your involvement with the collective Exploding Motor Car [EMC]? Was the name a reference to Cecil M. Hepworth’s fabulously strange and morbid film Explosion of a Motor Car (1900) (a.k.a. The Delights of Automobiling)? This early trick film—in which a car explodes and pieces of the car’s occupants fall from the sky in front of a policemen who proceeds to put them back together—seems to accurately encapsulate the spirit of the collective.

WH: Exploding Motor Car is the name of the film crew that was formed in art school consisting of Brett Long, Nick Wallace, Jepoy Garcia and myself. Later, Andrew Zukerman and Daijiro Hama became members. The name was supposed to be decided through a chance operation. We all wrote various names on tiny pieces of paper and threw them off of the second floor balcony at a mall in Mississauga, Ontario. We had decided whichever one landed in the mall fountain would be the winner. None of pieces made it into the fountain, but somehow we managed to settle on a name that day.

The collective was named after Hepworth’s film since it captured our enthusiasm for early cinema and illusions. EMC even had its own resident magician, Nick Wallace, who eventually became a national champion. There was something that was so captivating about those early trick films, partly due to their ingenuity but also due to the lack of an embodied, historical context. That is, it is impossible for a contemporary audience to fully comprehend what it must have been like to see these films in their original, historical context. Our desire was to create contemporary versions of these films, simple vignettes that would showcase a trick.

CE: EMC made some amazing music videos. Can you talk about some of the bands that the collective worked with? Can you describe a few of the techniques/tricks you were experimenting with?

WH: EMC began by creating music videos for our musician friends. We eventually ended up receiving some funding from MuchFACT and Factor for our more ambitious project.1

I think the music video for Timber Timbre’s Black Water (2011) best reflects our sentiments toward early cinema. The video had a simple premise: namely, the corpse of a drowned deep sea diver comes back to life and rises to the surface of the sea. The dead diver was composed of several puppets including a mask of singer Taylor Kirk’s face, and the sea life consisted of puppets constructed from whatever junk was lying around our studio. For instance, the jellyfish were made out of two baby parasols and the crabs were made out of gardening gloves and papier-mâché. The diver’s mask was created from a cracked lid. We filmed a hula skirt to resemble seaweed, and glass beads to mimic bubbles rising to the surface. When the images were flipped, their movement looked as though they were underwater.

We filmed the video on a crappy, digital Casio camera that shot 240 fps slow motion at 320 x 240 resolution. We transferred the video to 16mm film in order to up-res the video and to further obscure the underwater world. At the time, we were obsessed with Jean Painlevé and revered his use of effects and staging.

EMC didn’t only create music videos, we also did expanded cinema performances at parties and shows like Extermination Music Night in Toronto.2

CE: In addition to making films with EMC you also ran Film Fort, a nomadic screening series that ran from 2007-2009. Can you talk about Film Fort? What was your programming methodology?

WH: Film Fort was something I created a few years after film school with Marissa Neave. It was an attempt to get the artists that I admired to come and visit me instead of having to socialize at art events. I took a lot of cues from Peter Burr’s Cartune Xprez [a traveling animation party]. Their touring animation compilations were top notch. I liked how Burr placed older animation legends with younger, emerging animators.

I had a pretty solid gimmick to make the screenings feel laid back—namely, we would build a giant fort out of bed sheets and place cushions throughout an old loft, encouraging everyone to watch the films lying down. I have never liked watching experimental cinema in uncomfortable folding chairs.

There was not a methodology for selecting the artists; I do not have a curatorial background. Friends of friends would recommend artists and so on. It wasn’t funded. Bryan Belanger would let us use his loft and we would charge a small cover fee and sell beer. We usually broke even and Bryan was paid in beer.

We often moved our screenings in order to keep them from becoming stale.

CE: Let’s discuss some of your films. The Public Slaw begins with the physical manipulation of a 35mm DreamWorks trailer for the computer-animated martial arts comedy Kung Fu Panda (2008). Why did you choose Kung Fu Panda? Was it an attempt to juxtapose the digitally generated computer graphics with the materiality of film?

WH: A friend and I salvaged these 35mm trailers from a dumpster behind the historic Revue Cinema in Toronto. I was attempting to transform the aesthetically mundane into something abstract, organic and beautiful. The idea was to break down this slick computer animation into simple colours and shapes, freeing the work from its rigid computerized structure and forcing the digital and the analog to duke it out. This gesture was a response to working in the industry and provided an outlet for some of my frustrations with the polished animated image. My relationship with the animation industry is a complex one given that I do enjoy some polished, big-budget animated features.

CE: Can you talk about the role that Dracula plays in the film?

WH: Kevin plays the type of Dracula that would host VHS horror film compilations or the now cult, late-night horror television series of yesteryears. He re-assures the audience that their skepticism is indeed justified. He doesn’t have any dialogue because he was too nervous to deliver his lines.

CE: The end of the film is absolutely terrifying: a dance performance by Minae Omi reminiscent of ‘60s freak-out films. Shot on high-contrast, black-and-white film using handheld cameras and edited together using a succession of jarring cuts, the experience it creates for the viewer is quite visceral. Can you talk about your collaboration with Omi?

WH: We shot this scene at Artscape Gibraltar Point, a not-for-profit artist-run centre on Toronto Island. Andrew found a discarded tent that became the prop for her to interact with. He also altered a piano with a belt and some screws, and was playing this prepared piano to enhance the mood. A random guy walked into the room and started shaking his keys assuming that it was a performance that everyone was welcome to take part in. The dance itself was completely improvised.

C.E.: What exactly is “lazy paperteering”?

WH: In my films, all of the collage movements are done by hand against a green screen. In the end, I composite the images together. Most of the time, I have no idea how things will connect with one another—this is part of the laziness, but it is consistent with the serendipitous nature of collage. I think there is an energy that comes from this type of movement. For instance, these movements by hand are not consistent, creating a sense of unease in the viewer. These movements don’t correlate to animated motion. The use of green screen also confuses most viewers and this, I believe, is one of the reasons that they have the desire to figure out how these videos were created. Similar to watching magic tricks.

In the music video for Siamese Brutality, there is a moment where I leave the green screen in the shot and you can see an X-Acto knife struggling to move a collage cut out. This laziness not only reveals how the video was made, but creates a sense of struggle that plays into the energy of the song.

CE: Your work is often quite humorous. Can you talk about the tension between using experimental strategies and your desire to entertain? Does this come from working on music videos which, by their very nature, have to entertain an audience for the duration of the song? Or is this something more akin to an aesthetic philosophy?

WH: The ways in which vignettes cascade across each other, with no rhyme or reason, is a deliberate attempt to mimic a dream state. In film, it is possible to induce a dream state by creating moments that bleed into each other with no apparent direction or motivation.

I don’t know if entertain is the right word. I am trying to create work that is humorous, while providing a live-feed to my brain’s inner-workings. The fact that these collage movements are shot in live action means that my presence is felt in the work, hopefully strengthening the fact that these works stem from a form of stream of consciousness.

My first exposure to experimental cinema was Brakhage through the lens of MuchMusic. For instance, simply consider the content on MuchMusic’s The Wedge [television series], where many of the videos exploited experimental cinema techniques for entertainment purposes. Perhaps it was students being taught under the rubric of avant-garde cinema by the experimental filmmakers of the previous generation that allowed for this form of experimentainment.

CE: Do you feel your choice of juxtaposition reveals something about your subconscious like a form of André Breton’s “pure psychic automatism”?3 Do you see your work as a form of therapy?

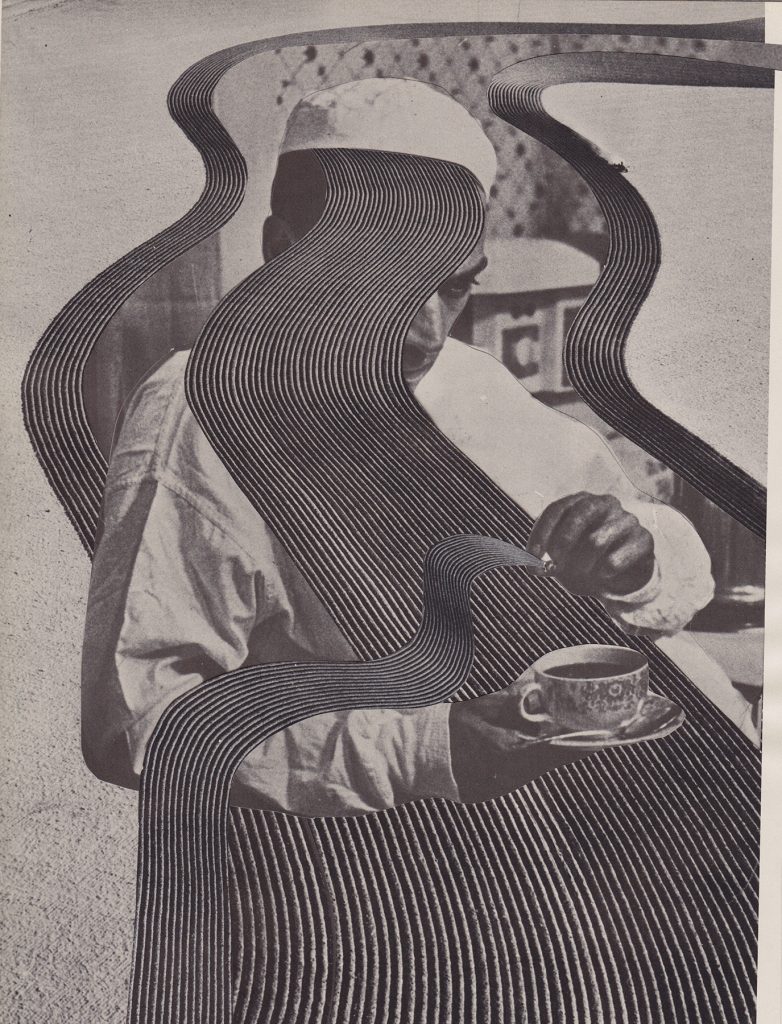

WH: Through my work, I am attempting to reveal the subconscious. I am a fairly guarded person but I think the work allows me to embrace a form of psychic automatism. The work is guided by free association and chance operations. I basically find images that work well together and randomly place videos overtop of each other in the timeline. I then find connections I didn’t see before and refine some of the compositions so that the eye will be guided through the moving layers.

As already indicated, one of the goals of the work is to simulate or create a dream state. The work is not intended as a direct interpretation of a dream, but I am trying to capture the feelings and images associated with dreaming. For instance, the confusion, the gore, the sex, the chaos, etc., that are omnipresent in dreams.

I am not sure if the work is a form of therapy, but perhaps it is some form of emotional stasis? I tend to bury myself in this collage world to avoid dealing with anxiety and day-to-day stress. The work is not only a form of entertainment but a complex form of avoidance.

CE: Can you talk about your approach to collage? Do you collect images and elements that you want to use or do you simply immerse yourself in vintage magazines? Are you mining databases online?

WH: There is a great place here in Portland called Scrap PDX, a Bulk Barn for art supplies and found ephemera. I have spent the last few months sourcing things from there but it feels a little too easy…like it has been pre-curated. When I was in Montreal, I would often salvage books from the store Renaissance. I like the idea of bringing magazine imagery back from the dead, taking things from the literal trash pile and giving them a permanent place on the Internet. For my collage work, I generally use physical images that come from magazines or books. However, when I started making collage videos I heavily mined the Prelinger archives. For instance, the music video for Worst in You was made with images found online. I am trying to get away from using old magazines and starting to focus on my own personal archive.

I generally follow some rules for the production of collage. The first one is limited use of Photoshop since collaging digitally gives you too many options. I think being limited to an X-Acto knife and a glue stick forces you to work slower and to question your decisions. It is often quite hard to slice into a great old image, but once you do there is no turning back. Command+Z is the antithesis of great collage.

CE: What are you looking for in the images you collect?

WH: Alternate gestures, masks, portals, overt and subliminal advertising, awkward portraits…

CE: Do you collect other forms of junk for artistic purposes?

WH: I used to have an addiction to Renaissance in Montreal. I worked directly across the street from it and would spend my lunch break scouring the store for oddities. Taking photographs of everything that I liked allowed me to get my fix without actually having to buy anything. In that way, I could archive objects without them taking up physical space. My favourites were objects with traces of people’s imprints. Personal objects like photos still in the frame or cameras with film left in them, books with writing, old answering machine tapes, crappy craft art and failed DIY home projects. I purged most of my collected junk when I moved to Portland and so far I have resisted the urge to collect anything other than collage material. I also throw away most of my collages or give them to people. I have everything scanned but I no longer feel the urge to hold onto items once they have been documented.

CE: Are your approaches similar when collecting moving images?

WH: I often look for the same types of images; however, with moving images, I think about how they will interact with other images from my archive. Sometimes a moving image will work better as a still image, so I will print it out and make a collage from it. I enjoy finding footage that can easily be transformed into a loop simply by adding a layer of paper. I feel like what I am doing is very much in line with the GIF scene that has evolved over the last few years.

CE: Recently, you worked with Steven Ellison (a.k.a. Flying Lotus) on a feature length horror film titled Kuso (2017). The film has been recently described as “the grossest movie ever made.”4Can you talk about your involvement with the project?

WH: I don’t think it comes close to being the grossest movie ever made. Working with Steve was great because we are both really fascinated and inspired by our dreams. We even discovered that we had both had the same dream involving Freddy Krueger as kids. Instead of being killed, in the dream we end up joining him on his killing spree.

Working on Kuso was like nothing I had done before. I was asked to stitch together nightmarish vignettes. I would create the collage transitions without sound, and then Steve would score them and add foley. My moving collages used imagery from old JET and Fangoria magazines—images that had made an early impression on Steve. Some of these horror images were also baked into the back of my brain at an early age—I can remember going into the video store with my parents and flipping over a VHS clamshell to see the images of gore featured on the back. It resulted in me drawing images of Freddy and Jason in kindergarten. My parents actually got a concerned phone call from one of the teachers. I think the film as a whole deals with Steve’s dreams and his childhood impressions while also paying tribute to his genre idols.

CE: Is there anything you would like to add?

WH: I wanted to try and answer these questions in a lucid dream. I didn’t quite get that to happen, but I did have a dream that you were in. This is what I wrote down after I woke up:

At night, you and I were walking along a very steep sidewalk headed to an art show—I think it was an expanded cinema performance. The sidewalk became so steep that we were almost sliding down it. We saw a tall blue iron ladder similar to the ones affixed to the tops of buildings. You made it up and were waiting at the top where the sidewalk was flat. As I made my way up the ladder I noticed that it had curved backwards, making my climb almost impossible unless I were to hoist my entire body over the top of it like a rock climber. My legs became immobile as I reached the top and I felt myself slipping. I asked you for help and you pulled me over the top of the ladder, except my pants and underwear got caught and were pulled down. I made it over and you put me down on the ground where I apologized repeatedly because, I think, my genitals had brushed up against your arm. We eventually made it to the show and it had turned into a screening on the history of psychedelic light shows but the wall that the film was being screened on was covered in iridescent scales that sent colourful lights moving in all directions. We found room on a couch and there was some sort of technical hiccup…the night was reminiscent of many of those that took place under the guise of Film Fort.

- MuchFACT [Much Foundation to Assist Canadian Talent] is a Canadian fund that provides grants to recording artists in order to help them produce music videos. It is funded entirely by Canadian television cable channels MuchMusic and MuchMoreMusic. Factor [The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings] is a private, non-profit organization dedicated to providing assistance toward the growth and development of the Canadian music industry. [↩]

- For a comprehensive history of Extermination Music Nights, see Jeremy Strachan, “Extermination Music Nights: Reanimating Toronto’s Lost Geographies in Sound and Art,” Echo 12.1 (2014). [↩]

- In The First Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), André Breton defines Surrealism as follows:

“Pure psychic automatism by means of which one intends to express, either verbally, or in writing, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, free of any aesthetic or moral concern.” (Translation by A. S. Kline.) [↩] - Chris Plante, “Kuso is the grossest movie ever made,” The Verge (January 25, 2017). [↩]