Scrapbook: From the Archives of Dave Barber, edited by Andrew Burke and Clint Enns (Winnipeg: Winnipeg Film Group, 2025).

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Andrew Burke and Clint Enns

WHY DID THEY HIRE ME?

CONFESSIONS OF A CINEMATHEQUE PROGRAMMER

MARKETING IN THE COLDEST CITY

TALES FROM THE ‘THEQUE

THE JOYS AND SORROWS OF BEING A CINEMATHEQUE PROJECTIONIST

DAVE BARBER, FILMMAKER

DAVE BARBER, SURREALIST

DAVE BARBER, JUVENILE DELINQUENT

DAVE BARBER, GOES TO COLLAGE

DAVE BARBER, POET

DAVE BARBER, INTERIOR DESIGNER

DAVE BARBER, FOLK ENTHUSIAST

DAVE BARBER, FILM HISTORIAN

DAVE BARBER, CRITIC

DAVE BARBER, WILL BE REMEMBERED

DAVE BARBER, ICON

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Complied by Clint Enns

Introduction

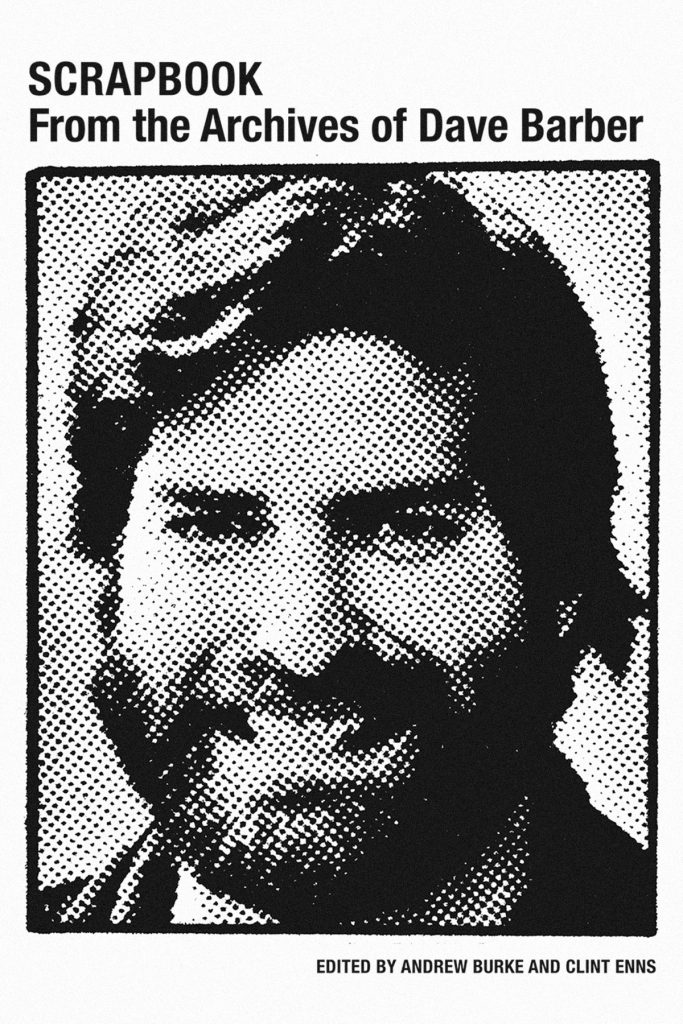

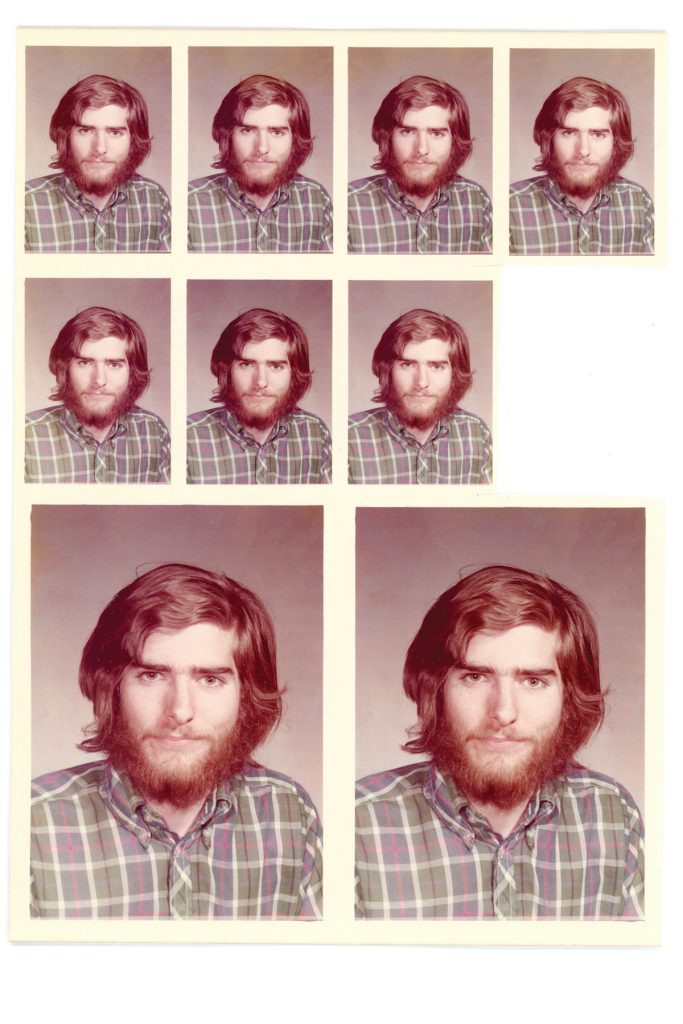

In the chronicles of Canadian cinema heritage, Dave Barber is a legend. Longtime senior programmer of the Winnipeg Film Group Cinematheque, a fixture at festivals such as the Toronto International Film Festival and Hot Docs, and champion of independent filmmaking, Dave Barber is a cultural icon. With his furrowed brow, trademark beard, and wide array of plaid shirts, Dave cut a distinct figure in Canadian cinematic circles and has been widely celebrated in his hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba. The cinema that he programmed for nearly forty years now bears his name: the Dave Barber Cinematheque.

This book is compiled from material found in forty-seven boxes, each filled to the brim with fragments and fragments of fragments: pages one, four, and seven of a printed out email, handwritten notes, doodles and drawings, to-do lists, telephone numbers, top tens, postcards, photographs, pieces of paper with hundreds of push-pin holes from being posted and reposted on various bulletin boards and walls, photocopies, photocopies of photocopies, newspaper clippings, program notes, interview questions, bills, posters, Cinematheque programs, programs from other cinemas, handbills, letters, and many other random bits and pieces that Dave held on to and which held some significance to him. There was no order to any of the material and most of it could be considered incomplete in some way or another. Nevertheless, to open these boxes is to get a sense of who Dave was and what mattered to him. In sharing a selection of the material here, we hope to have captured something of the richness of his life, the warmth of his demeanour, the depths of his passions, and the idiosyncrasies of his observations of cinema, life, and the world. These boxes consist of items saved from Dave’s apartment, from his desk at the Winnipeg Film Group, and from a storage closet at the WFG where Dave secretly tucked away stuff that was destined for the dumpster but which he recognized was of value and significance. As such they constitute the Dave Barber Archives, the unofficial archive of the Winnipeg Film Group and the Cinematheque that, with their acquisition, have been made official. We are enormously grateful to the Barber family for gifting this material to the Winnipeg Film Group. The Barber family’s gift has ensured that key artefacts that tell the story of the WFG, the Cinematheque, and of Winnipeg film culture from the 1970s to the 2020s will be preserved. The Barber family entrusted this material to Dave’s good friends and colleagues David Knipe and Jaimz Asmundson, who, aware of its importance, ensured that the key elements were saved and began the process of assigning an order to it. Their work, done even as they were grieving the loss of Dave, has made this book possible.

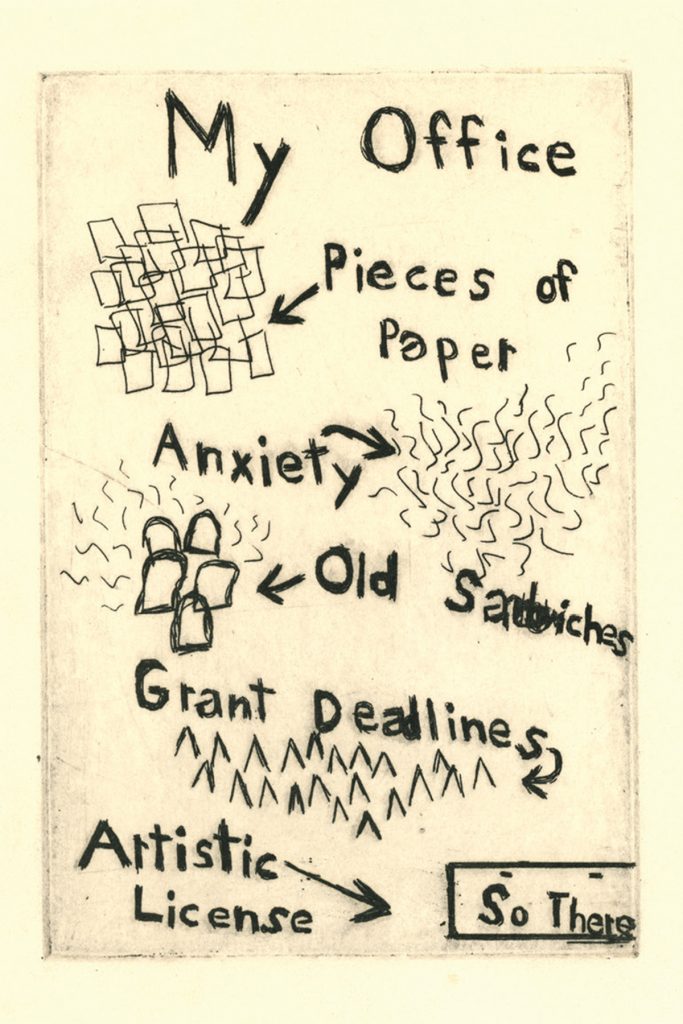

In order to produce Scrapbook, we dove into these forty-seven boxes and sorted the material thematically, recognizing that a simple chronological account of Dave’s life and work would not capture the complexity of his thinking and passions, or the sheer breadth of his interests and activities. We cheated a bit here and there to include things that weren’t in the collection, but which are key to understanding Dave or provide insight into some aspect of his life or personality. Nevertheless, our goal was to remain true to the boxes, not least because their somewhat chaotic unsortedness reminded us of Dave. As all those who have worked alongside him will attest, his desk could be a bit messy, and Dave worked best surrounded by the kinds of scraps and fragments of paper that ended up in the boxes and which now constitute the Dave Barber Archive. Let us not mince words: Dave was a packrat, but this tendency now seems like a gift. Dave saved all the things that others would not, and as such, we have a record of the past that is uniquely Dave’s.

Our focus here is, to a significant degree, on Dave’s professional life. As such, Scrapbook begins with the September 4, 1982 Winnipeg Free Press ad for a part-time programmer for the newly founded Cinematheque of the Winnipeg Film Group. Dave’s successful letter of application, preserved here in draft form, marks a significant moment in his life. Film was always among Dave’s passions, but at this point it became his career and the field in which he would make what is perhaps his most significant social and cultural contributions. Dave was integral to the development of filmmaking in Manitoba. He recognized that the Cinematheque was a branch of the Winnipeg Film Group and took seriously his role to show films that would inspire the future filmmakers that populated the audiences. His work as a programmer also cultivated a wider community of Cinematheque-goers whose film horizons were expanded by the films he brought in, whether as entire seasons focused on obscure classics or midnight screenings that showcased the schlocky and the strange.

Dave’s work as a programmer cannot be disentangled from his other passions and from his unique personality. You will find in here a full range of materials that speak to Dave’s oddball interests and idiosyncratic fascinations, from his teenage membership in the obscure U.K. paranormal society The Ghost Club, to his ongoing efforts to describe the perfection of fried luncheon meat, to his commitment to writing letters to the editor, dozens of which he sent even as a teenager. In this book as in real life, Dave Barber, Filmmaker exists alongside Dave Barber, Folk Enthusiast;Dave Barber, Critic exists alongside Dave Barber, Surrealist. The sheer range of Dave’s enthusiasms are in evidence in the material he saved, but there is also a sense that Dave, in the collection of this material, was in pursuit of a grand project that went even beyond the book on the Winnipeg Film Group he had hoped to write. These boxes are Dave’s version of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, scraps and fragments that represent his philosophical reflections on everyday life as well as the trials and tribulations of being a cinematheque programmer.

We have called the collection Scrapbook not simply because it is made up of fragments, but because Dave was an avid practitioner of the form. The boxes contained a series of teenage scrapbooks full of clippings from newspapers and magazines on a wide variety of subjects. Music and film predominate, but they also include unusual news stories and seemingly random selections, ample evidence that Dave developed his appetite for the surreal early. True to the idea of the scrapbook, we have left much of the material in its original form: mock-ups of Cinematheque programmes and posters complete with tape, clippings with torn edges, notepaper with doodles and coffee stains, complete articles ripped from magazines, the yellowing paper of a news article, and so on. To call this a Scrapbook is to honour the fragmentary nature of the material that Dave left behind, but also to think about how he himself might have put it together. An additional bonus is that Scrapbook somehow feels like the title of a lost LP by one of the English folk artists—Nick Drake or Fairport Convention—that Dave loved.

Scattered throughout the forty-seven boxes were also mementoes of Dave’s close relationship to his family: pictures of childhood family vacations, super 8 films made with his brothers, images of Dave at family occasions awkwardly decked out in a suit, snapshots of summers spent at the lake and, from more recent years, birthday cards, letters from his mother who had retired to Victoria, and drawings and notes from his beloved nieces and nephews. Dave was a loved son, brother, and uncle, and this aspect of his life, his closeness with his family and the love he had for them, was one many of us occasionally got to hear bits and pieces of but were never fully privy to. We have not included much of that personal material here, choosing instead to focus on Dave’s professional and public life, but, as much as Dave is synonymous with cinema in Winnipeg, it should go without saying that Dave had a life beyond the cinema. There’s no doubt that Dave was supported and sustained by these familial connections. Even teenage rebel Dave conscripted his brothers and dad into his super 8 productions, and these are marked by a total sense of rambunctious family fun.

Dave was born in 1953 and grew up in Winnipeg. His father, Clarence Barber, taught economics at the University of Manitoba. As Dave notes in a Lives Lived column he wrote for the Globe and Mail on his father, his work was instrumental in the provincial government’s decision to build the Red River Floodway. His father’s academic career meant that Dave traveled around the world at a young age. When he was a child, he lived briefly in the Philippines, attending a primary school run by the Philippine Women’s University. His report card notes that, even at that young age, he expressed a real interest in books and reading. His father’s travels also took him to London and Spain. His time in the UK was especially significant. Already a passionate lover of rock and folk, Dave attended the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970—tape recorder in hand—and saw Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Jimi Hendrix, and The Who there. He also sometimes spoke wistfully about falling in love with a girl from Dundee.

Throughout his childhood, his father would take him to the movies. His earliest cinematic memories include being terrified of the cyclops in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, getting chills when the giant statue in Jason and the Argonauts turns its head, not finding Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday funny (which he later suggests was due to being impatient and immature), being scared to death by Robert Wise’s The Haunting, which remained one of his favourite horror films, and loving Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack to Our Man Flint so much that he bought the record, the first record he ever owned.

In grade ten, he organized a film club at Kelvin High School. Largely a one-man operation, Dave programmed the screenings, designed the posters, and ordered the films through the National Film Board of Canada’s Winnipeg office. One of these posters now graces the entrance of the Dave Barber Cinematheque and is evidence of both Dave’s programming talents and promotional skills. The mixture of slapstick comedy and serious documentary would later characterize his work at the Cinematheque. Also in typical Dave fashion, he did not seek official permission to set up the club and was reprimanded in a strongly worded letter from the principal who told him the club was ultra vires or “beyond the powers.” That Dave set up a film club he didn’t technically have the authority to set up is in every way a Dave move, and doing things because they were necessary and important, rather than authorized and approved, is the kind of rebellion that punctuates Dave’s programming philosophy and practice.

Dave later attended the University of Manitoba where he received a BA in psychology with a minor in film. Psychology may seem an odd choice, yet the archive demonstrates that Dave remained interested throughout his life in what made people tick. Although Dave was only one course short of becoming a film major, it was already clear that he aspired to work in the film or music industry, and much of his writing in The Manitoban draws on his extensive knowledge of music, movies, and the media. He later went back to school to get a Communications diploma from Red River Community College, where he continued his journalistic work as a staff writer for The Projector and even wrote an acclaimed one-act play: Where is Raymond Dubois Now that We Need Him? Hailed by the Winnipeg Free Press as a quality farce, the play shows Dave’s love of the absurd and his schooling in silent-era comedies. During this period, Dave was also an avid, if unpaid, promoter of folk music, distributing his own newsletter called Folk News. Looking through the issues of Folk News, it is easy to imagine an alternate timeline, one where Dave finds a position in the world of folk music, as a journalist, in public relations, or in programming the Winnipeg Folk Festival itself. But music’s loss was cinema’s gain.

Upon completion of his diploma at Red River, Dave wrote a handful of articles for both the Free Press and the Winnipeg Sun, trying to get his foot in the door at these publications. During this time, Dave published two significant articles in the long-defunctWinnipeg Magazine that put the city front and centre in film history. The first of these, “A Funny thing Happened on the way to the Poolroom,” details the fateful meeting of Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx at Winnipeg’s Windsor Hotel, a pivotal moment in each performer’s career. A product of meticulous research in the microfilm era, the article exemplifies that feeling, often expressed by Dave himself, that Winnipeg is really the secret heart of everything, the place where chance encounters that would change the trajectory of cinema could and did happen. When the Windsor Hotel burned down in 2023, every news story recounted this tale of Chaplin and Marx meeting there. Rest assured, while this has passed into common knowledge, it is the result of Dave’s rigorous research. A subsequent article, “Travels with Charlie” details Chaplin’s time in Winnipeg asking, “[Chaplin] remembered Winnipeg [but] did Winnipeg remember Chaplin?” Dave answers the question himself: “Not especially.” Yet, thanks to Dave’s investigative legwork, the story of Chaplin in Winnipeg has become common currency, something celebrated if not properly cited.

It was at this point, in 1982, that the fateful ad for a Cinematheque programmer appeared and Dave, seemingly well on his way into a career in journalism, found himself at the Winnipeg Film Group, where they immediately recognized that he would give the position his all. As Len Klady, who led the search committee, later told Dave, “it was between you and another person, but we felt you would work harder.” In the early years, the Cinematheque shared a space and programme guide with the NFB. Dave threw himself into the job, programming experimental Canadian cinema, animation, comedy classics, and the arthouse films of the day. What is striking about his work in these early years is its adventurousness and breadth. His focus on surrealism put his work at the Cinematheque in conversation with the films of John Paizs and early Guy Maddin, and what would eventually blossom into, as Geoff Pevere famously phrased it, “prairie postmodernism.” Alongside this work, Dave programmed a wealth of feminist cinema, from spiky punk cinema such as Smithereens to experimental sci-fi such as Born in Flames, and was ahead of the curve on the celebration of low-budget, camp, and cult cinema. Though the name precedes him, Dave clearly took seriously the idea that he was the programmer for a cinematheque. He understood that he had an educational mandate, but was also in charge of challenging his audience and cultivating a civic cinephilia, something that persists to this day thanks to the work that he did. But this doesn’t mean it was all earnest screenings of the arthouse canon. Dave was a man of taste, both good and bad, and any weekend could include screenings of both Stalker and Santa Claus Conquered the Martians, Persona and Plan 9 to Outer Space, Rashomon and Reefer Madness.

One of our arguments here is that Dave’s programming represents an important intervention into the history of Canadian cinema and the history of cinematic exhibition in Canada. Dave is not alone in this enterprise—he would become friends and maintain an ongoing correspondence with Jim Sinclair at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver and Gordon Parsons at Wormwood’s Dog and Monkey Cinema in Halifax—but there is something special about Dave’s position as a programmer for a cinema attached to an artist-run film production centre with a distribution wing. One of the main reasons that Dave held the esteem of the Canadian cinema community is that he understood filmmakers. It is not surprising that many established Canadian filmmakers championed Dave and continue to sing his praises. He supported them while they were still unknown, screening their films, offering words of encouragement, and inviting them to Winnipeg in the middle of winter. He understood the struggles filmmakers went through to realize their visions and with the difficulties associated with distributing Canadian films. He also had made films himself in his youth and would return to doing so in the decades that followed. In his years at the WFG, his desk was, in many ways, the centre of the organization, both at the house on Adelaide Street and later in the Artspace Building. For emerging filmmakers, Dave was an ally not a gatekeeper. Bring him something unique and ambitious, and he was likely to play it whatever its shortcomings and despite its low budget. This didn’t mean that he wasn’t critical, he was just generous and recognized that filmmakers won’t have a chance to make more sophisticated works if they don’t receive support in their formative years. Not only was Dave an inspiration to filmmakers, but he served as a mentor to several generations of programmers. If we have a secret ambition for this book, it is to ensure that Dave’s programming methodologies and principles are carried into the future, that this book is a record not simply of the work that he did, but also a guide for how to do the work.

Dave didn’t stop writing. There was the copy for the program guides, of course, but for a 1991 special issue of Independent Eye dedicated to film exhibition–wittily titled Exhibitionists–he contributed an article titled “Confessions of a Cinematheque Coordinator or I Wish God Rode a Harley for the Canadian Film Industry.” The title immediately evokes Les Blank, one of Dave’s favourite filmmakers, and the whole article is reminiscent of Blank’s irreverent yet incisive style. “Confessions” focuses on one of the main dilemmas that Dave faced as a programmer, namely, the difficulties associated with marketing Canadian cinema. In order to make his argument, Dave works from personal anecdotes and experience. The article showcases Dave’s capacity for telling stories, and exemplifies his ability to build complex argument out of the nuts and bolts of everyday situations. One of the things that makes the piece so powerful is that you can see Dave really cares; he makes the invisible labour of programming visible, shows the invention involved in getting bums in seats, and lays bare the emotional, even physical toll, of running a cinematheque. At the end of the article, Dave writes,

In this stressful time of cutback and recession, it is easy for people in the cultural and artist communities across this country to become depressed […] Our solution is to go laughingly against the grain. The WFG’s group of volunteers […] comprise a faithful lot who are not about to give up on Canadian film.

Dave’s devotion meant that he did not easily succumb to depression. He was a fighter for Canadian cinema, but these battles took their toll. Dave would often note that his work literally gave him ulcers. Nevertheless, he took immense pride in his work. Writing in Rough Cut, the WFG’s in-house newsletter, in 1994, Dave says, “What I am most proud of is the dedication and commitment we have given to the promotion of Canadian film. It is as necessary now as it was twelve years ago.”

Always committed to finding new ways to promote Canadian cinema and getting new patrons to the Cinematheque, Dave, in collaboration with Jaimz Asmundson, embarked on a series of innovative promotional spots for the Cinematheque in the late 2010s and early 2020s. These spots are charmingly low-budget, yet skillfully made, mini-masterpieces of promotion and can be seen as nostalgic throw-backs to regional television commercials of bygone eras. Perhaps most famously, Jaimz and Dave, dressed in suits, took to the streets of Winnipeg in winter to “preach the gospel of Canadian cinema.” The ad is hilarious, with bemused passers-by shuffling by nervously, and is in every way a continuation of Dave’s devotion to the cause. In the doldrums of the pandemic, Jaimz and Dave produced Dialing for Deals, with Dave taking to the phones to sell Winnipeggers unlimited annual passes to access the Cinematheque’s online offerings. The spot captures Dave’s comic energy and in every way demonstrates that Dave knew that showmanship was part of his job as well.

Dave is a well-decorated celluloid soldier. In 1999, he was the recipient of a Blizzard for “Outstanding Achievement for contributions to film and video in Manitoba.” We have included the notes for his acceptance speech in this collection as Dave, ever humble, mostly chalks up his success to the larger team at the WFG rather than accepting it as his own. In 2004, he was honoured by the Manitoba Foundation of the Arts for his work at the Cinematheque. And in 2007, he received the Winnipeg Arts Council’s “Making a Difference Award.” In his letter of nomination, filmmaker Matthew Rankin pinpoints precisely what distinguishes Dave’s contribution to the cinematic landscape of Winnipeg:

He is a cultural pioneer, who managed to break down Winnipeg’s notorious isolation. In the process, Dave not only enriched Winnipeg culture, but most crucially he introduced emergent film talents in Winnipeg to the cinema of the world. A cinematic culture does not emerge in a vacuum, and in the work of every Winnipeg filmmaker are ideas and visions that began their gestation in Dave’s programs. Dave’s place in the annals of Winnipeg film history is also assured by his extraordinary devotion to the development of an indigenous Winnipeg cinema. He programs and promotes even the lowliest of local films with the same enthusiasm, vigour, and publicity as he does the work of any international film master. The Cinematheque is the only theatre in Winnipeg where the general public can consistently encounter Winnipeg cinema. Without Dave many local films would be lost to the mists of oblivion and local filmmakers would never discover their talent for communicating with an audience. In other words, Dave supported local filmmakers regardless of stature and this is significant, not only for the filmmakers themselves, but for Winnipeg as a whole. What’s more, it is only because of this groundwork in Winnipeg itself that the city’s filmmaking has become known on a national and international level.

In other words, Dave supported local filmmakers regardless of stature and this is significant, not only for the filmmakers themselves, but for Winnipeg as a whole. What’s more, it is only because of this groundwork in Winnipeg itself that the city’s filmmaking has become known on a national and international level.

Sticking with awards, in 2013, Dave accidentally received the Queen’s Jubilee Medal from Manitoba Premier Greg Selinger. This story prompted Dave’s return to filmmaking. An avid super 8 filmmaker in his teenage years and already a self-described “ruthless editor” based on that experience, 2014’s Will the Real Dave Barber Please Stand Up? picks up where he left off, even borrowing visual tropes from his earlier works. The film is marked by a lightness of touch, wry wit, and a sense of the absurd that makes it a low-key classic of exactly the sort that Dave himself might program. We have included the full script here, as well as some classic Dave anecdotes about his experience when the film screened at Hot Docs. The cosmic irony of the Queen’s Jubilee debacle that is the subject of the film is that Dave had long been obsessed with his namesakes, and had long clipped articles from newspapers that could have been about him: from “Barber is Dull to Watch But Tough to Stop” (about 70s Philadelphia Flyers left-winger Bill Barber) to “Liv Ullman wins ‘David’” (about Ullman winning a Donatello David at the Italian Film Awards for Scenes from a Marriage).

In the late 2010s, in collaboration with Kevin Nikkel, Dave directed Tales from the Winnipeg Film Group. As the title suggests, the film is not meant to be a comprehensive or the definitive history of the organization. Instead, it brings together a number of filmmakers, administrators, employees, and affiliates to provide their takes on the WFG and its sometimes tumultuous history. As Nikkel observes in his oral history of the organization, Establishing Shots, the film relies on Dave’s institutional memory to recall and recount the different eras of the WFG’s history. For all the change that unfolded around him, Dave was there throughout. His keen sense of what to save and salvage, what ended up in the forty-seven boxes, continues this legacy, the institutional memory of the organization that he represented. But Dave was more than an advisor on the film, he and Nikkel worked collaboratively in conducting the interviews, organizing the mass of visual materials, and crafting the narrative that the film tells.

Dave’s work on Tales renewed his desire to produce his own book, which would draw on the archive of WFG and Cinematheque materials he had amassed over the years. As part of this process, he compiled a list of objects he was determined to include in any such history. Scrapbook stays true to this list, including several things that Dave felt were integral to any story of the WFG that he could tell, including, perhaps most significantly, the memorials for projectionists Witold Podszus and Winston Washington Moxam, both of whom Dave greatly respected and whose passings shook him tremendously. There were a few things that we were unable to track down, such as a letter from Marv Newland, famed director of Bambi Meets Godzilla, in which he discusses Winnipeg animators. There were a few other things that baffled us as well as being untraceable: Why would Dave have wanted to include a Winnipeg Free Press article with the headline “Peter Donaldson sent to prison for threatening to kill people”? But thankfully, we were able to find everything else that Dave had marked for inclusion. We have included many other things here in the hopes of making up for these few missing elements, and we hope Scrapbook captures the spirit of the book Dave envisioned. Most importantly, we wanted to do Dave and his legacy proud.

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been without the help of everyone at the Winnipeg Film Group. Without Jaimz Asmundson and David Knipe there would be no boxes and, hence, no Dave Barber Archive. We wish we would be able to celebrate the completion of this book with Jaimz, and are pretty sure he would have loved it. Luckily, we were able to share with him an early draft and his feedback, sensitivities, and insights were invaluable. We are grateful to Kevin Nikkel for his enthusiasm, feedback, and support, and would like to thank Mike Hoolboom for going through an early draft and providing constructive criticism. Mike Maryniuk, Walter Forsberg, Matthew Rankin, and Patrick Lowe helped fill in some of the blanks providing invaluable information, details, anecdotes, and images. Susan Algie of the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation helped us scan Dave’s early posters and her enthusiasm for the project was infectious. We are indebted to past work on the Winnipeg Film Group and would especially like to acknowledge Dave’s good friend, the late Howard Curle, whose knowledge of the history of the WFG was second to none.

We would like to thank Leslie Supnet, Karen Remoto, and Kier-La Janisse for keeping us on track, providing feedback on drafts, and helping with some of the administrative aspects of the project. Shout out to Diana Hotka whose archival insights were invaluable. Finally, we would like to thank Winnipeg Film Group staff—Olivia Norquay, Jillian Groening, Eric Peterson, Nic Kaneski, Mahlet Cuff, Luke Roach, and Skye Callow—whose warmth and encouragement was indispensable. Special thanks to K. Michalski and Candida Rifkind whose support has made this book (and almost everything else in our lives) possible.

Above all, thanks once again must go to the Barber family, whose generosity has made this project possible.

This book was designed by the legendary Mark Remoquillo. He made the project shine.

We would like to thank the Canada Council for the Arts and the Winnipeg Foundation for their support, and we would like to acknowledge that Clint Enns and Andrew Burke are currently supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We are grateful for their support.

Limited Edition Postcards

Critical Discourse

Winnipeg Film Group programmer left no scrap behind

Ben Waldman, “Winnipeg Film Group programmer left no scrap behind,” Winnipeg Free Press (September 26, 2025): C1-2.

Dave Barber kept nearly everything. His family, friends and co-workers knew this, but still, when he died in 2021, members of the longtime Winnipeg Film Group programmer’s inner circle were astonished by the variety contained in Barber’s personal archive, which held more than 50 years’ worth of typewritten letters — to Groucho Marx, to George Lucas, to the makers of Hawkins Cheezies — plus hand-designed leaflets, ambulance bills, inane newspaper clippings, Cinematheque programs, nuclear fallout plans, printed-out emails and one-of-a-kind bits of Canadian film arcana.

“Not literally, but sort of literally, a cheese-sandwich recipe was next to the earliest bylaws for the Winnipeg Film Group,” says filmmaker and writer, Clint Enns.

Over the past three years, Enns and Andrew Burke, a professor at the University of Winnipeg, sifted through 47 banker’s boxes filled with Barber’s personal effects — narrowing the trove down to produce a touching, hilarious and all-encompassing portrait of the city’s most devoted evangelist for independent film, clarifying the enduring vision that underlied his pack-rattish tendencies.

Scrapbook: From the Archives of Dave Barber will have its launch Sunday at 7 p.m. at the Dave Barber Cinematheque as the closing event of We’re Still Here, the film group’s festival celebrating its 50th anniversary.

While Barber is best known for his work with the film group — whose creative output and outlook he nurtured during his 40-year tenure there — Scrapbook gives readers and perusers a more well-rounded depiction across its 288 pages, thoughtfully designed by Mark Remoquillo.

Among its 16 chapters are Dave Barber, Filmmaker; Dave Barber, Juvenile Delinquent; and Dave Barber, Poet.

The book opens with a chapter titled Why Did They Hire Me?, which includes Barber’s resumé, circa 1982; his application to the programming job (“I’m extremely interested in the position and I think I could do a good job especially relating to programming and promotion”); and a list titled “Tasks I would like to do in my future job.”

Those tasks included having an effect, making a mark and making a difference. Among the labour he wouldn’t like? Sales/insurance/banking/real estate; dull, repetitive work; and working with assholes.

No matter the section, Barber’s passion for local art is always matched with an earnest brand of chutzpah mixed with inspiring zeal: if nothing was ventured, nothing could be gained.

In one missive, written in 1987, Barber politely makes suggestions to Piers Handling of the Toronto Film Festival, which had yet to go international. “I have greatly appreciated the fact that the (Canadian Perspective) program reflects films around the country. The reason I’m writing to you is because I feel this part of the festival is weaker than it was a few years ago. My criticism is twofold …” he wrote.

In a letter to Warner Brothers’ promotion department in Burbank, Calif., Barber goes to bat for Winnipeg band Mood Jga Jga, which had signed to the label but in Barber’s estimation, hadn’t received substantial juice for their self-titled record in 1974.

“I’m probably dreaming but maybe you could fly them down to California to do a few shows. God knows you must make enough money off your Black Sabbaths on the label to afford this,” a 20-year-old Barber wrote.

“To summarize, Mood Jga Jga is a damn fine band just starting out. Help them out with some promotion before they get discouraged. OK?”

Burke and Enns also republish influential articles written by Barber for the defunct periodical Winnipeg Magazine, including a 1982 piece that popularized and publicized the fact that Groucho Marx first saw Charlie Chaplin perform during a three-hour layover in Winnipeg in August 1913.

Barber made that conclusion through painstaking research of microfilm, cross-referencing four Marx Brothers publications. “And each time, Groucho was certain of the location,” wrote Barber, who reached out unsuccessfully for confirmation from the mustachioed comedian.

“And after all, how could you forget a name like Winnipeg?”

“Part of this book has the self-deprecating streak that Dave himself would have had,” says Burke, who specializes in film, television and cultural studies. “But then we’re also playing this game where we want people to take Dave seriously, because we think Dave gets undervalued as a writer and a thinker.”

Barber kept nearly everything, and Scrapbook is itself worth holding onto.

Making Scrapbooks: The Real Dave Barber, an interview with Andrew Burke and Clint Enns

Stephen Broomer, “Making Scrapbooks: The Real Dave Barber, an interview with Andrew Burke and Clint Enns,” Black Zero (2025).

In this short interview, Burke and Enns reflect on Barber’s decades of work as a champion of independent and experimental cinema in the prairies. From his early days helping to shape the Winnipeg Film Group into a national institution, to his tireless efforts in curating programs that gave visibility to local voices and a broader Canadian independent film culture, Barber emerges as a figure who sustained a unique cultural ecosystem against the odds.

We discuss the process of assembling the book, the challenges of capturing Barber’s multifaceted role as programmer, mentor, and community builder, how the book represents and balances his many passions, and the significance of his work in positioning Winnipeg as a hub of alternative film culture in Canada.

Whether you’re a filmmaker, film historian, or simply curious about how small communities sustain vibrant artistic life, this is a tribute to one of the central programmers who made that possible.

Essential Non-fiction Film, Music, and Culture Books of 2025

Kier-La Janisse, “Essential Non-fiction Film, Music, and Culture Books of 2025,” Spectacular Optical (November 30, 2025).

Dave Barber, iconic longtime programmer of the Winnipeg Film Group’s Cinematheque (which is now named in his honour) left behind a treasure trove of writings, drawings, programmes, post-it notes, correspondences and half-baked ideas that offer a perspective on half a century of Canadian cinema that is unique to Dave’s weird brain (this was a man who loved fried Klik, the poor man’s Spam). Lovingly and humorously assembled by editors Clint Enns and Andrew Burke, this book functions as a gateway to the kind of self-deprecating in-joke that could only come from Winnipeg.

Books of 2025

Sukhdev Sandhu, “7/31: Books 2025,” The Colloquium for Unpopular Culture (December 8, 2025).

Books of 2025 – 7/31: Andrew Burke & Clint Enns (eds.),Scrapbook: From The Archives of Dave Barber (The Winnipeg Film Group). Barber (1953-2021) was, for many decades, the Senior Film Programmer of the Winnipeg Film Groups’s Cinematheque. Decades of screening small films, old films, artist films. All the films the market doesn’t want us to see. Decades of promoting Canadian independent filmmakers.

Day after day of trying to bring in audiences. Make sure staff get paid. Deal with broken air conditioning, scratchy prints, projectionists who show up to work drunk. No wonder he got ulcers, the blues. When he died, his colleagues found 47 boxes full of … stuff. Clippings, newsletters, endless photocopies. A life in paper as much as in celluloid.

Burke & Enns have assembled a magnificent conspectus of his parallel selves – the programmer, filmmaker, folk rock fan, critic. It’s a model of affectionate biography, a chronicle of how to work within a sometimes trying institution, and (also) a really helpful entry point for anyone wanting to learn about Canadian cinema.